A safe harbour offers a place of refuge. Those in peril (or evading taxes), running before a storm, crossing a figurative bar to welcome respite. Non-figurative harbours, the coastal kind, have traditionally provided safe haven for mariners escaping inclement weather or foes.

Harbours fill and are emptied of seawater on the tide. Sea water that enters or exits is commonly focussed through narrow inlets. Here, powerful currents are generated that carry fish, sediment, flotsam, and unwary boats. Filling on an incoming tide is like a cleansing, a renewal; outgoing tides reveal channel arteries that keep alive the bars and broad flats of mud and sand, textured Kandinsky-like.

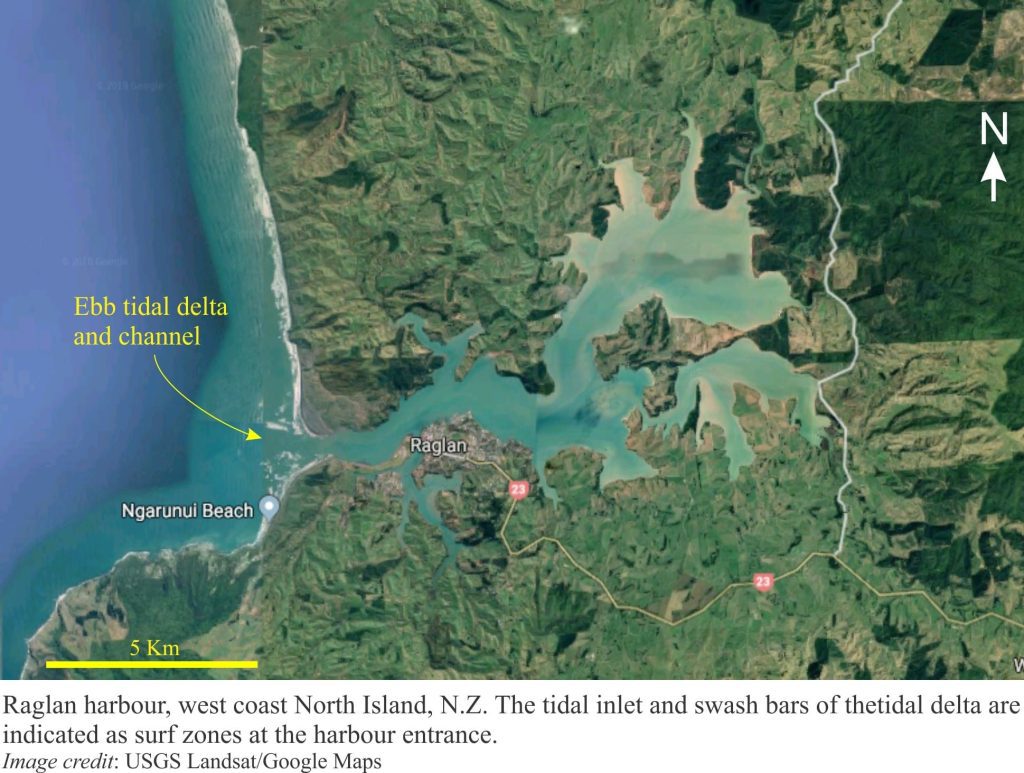

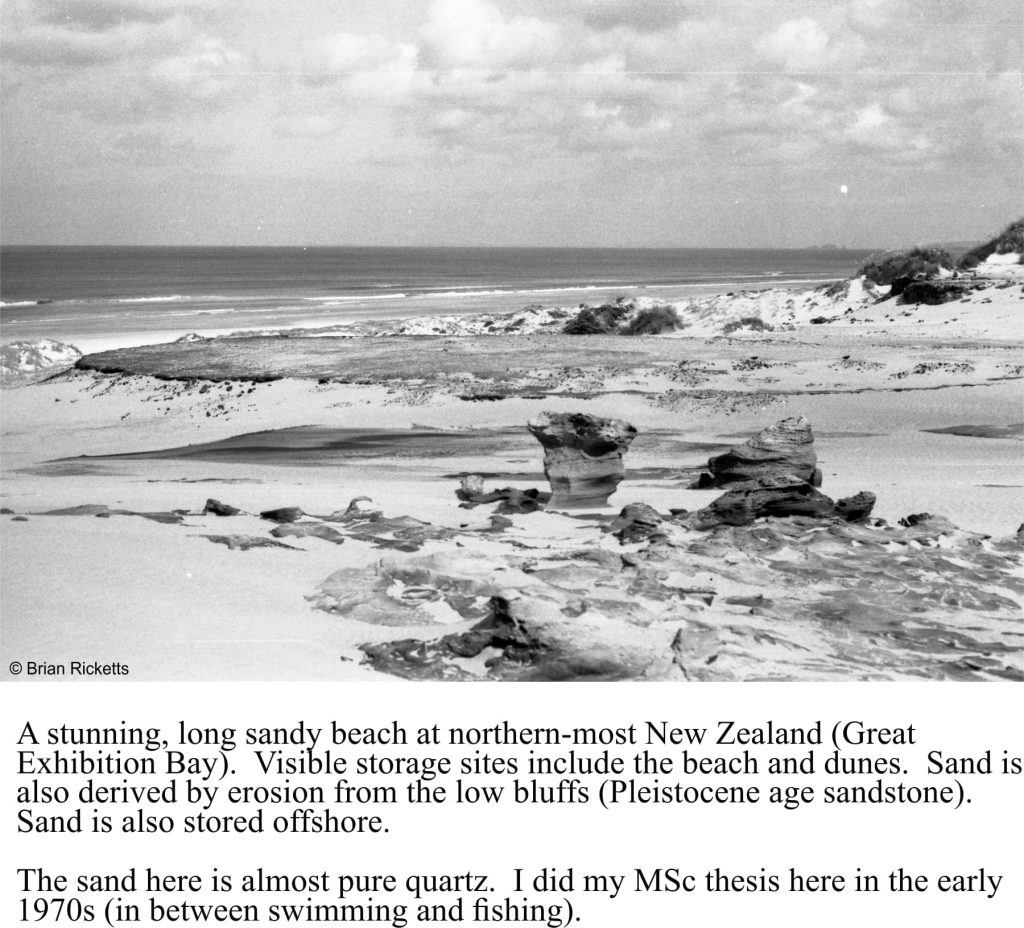

Northern New Zealand’s west coast has 6 harbours distributed along a 300 km stretch of coast. Each is protected by large sand barriers that have built over the last 2-3 million years with sand moved inshore by successive rises and falls of sea level.

Many of New Zealand’s harbours are drowned valleys, where rising sea level (following the last glaciation) has inundated dissected landscapes. Rising seas have crept up valleys, leaving the exposed high ground to front an intricately embayed coastline, islands, and estuaries that extend their marine fingers far inland.

New Zealand’s west coast is open to large swells, generated by westerly winds across a 2000 km expanse of Tasman Sea. Sea conditions along this coast are often rough. Access to the open sea via harbour inlets, requires sailors to ‘cross the bar’ – the zone of shallow, constantly moving sand. Strong tidal currents, particularly out-going tides can increase wave heights even further, as well as making wave conditions in general very choppy. The sea condition can change rapidly. Many a boat has come to grief across these west coast bars, a mix of bad luck and poor judgement (NIWA has real-time images of current bar conditions at several locations).

The oceanographic and geological term for sand bars at the entrance to harbours and lagoons is tidal delta. Tidal deltas can form on the seaward margin, in which case they are called ebb tidal deltas (because they are downstream of the outgoing tide). Those that form inside harbours and lagoons are flood tidal deltas where sand is deposited by incoming tides.

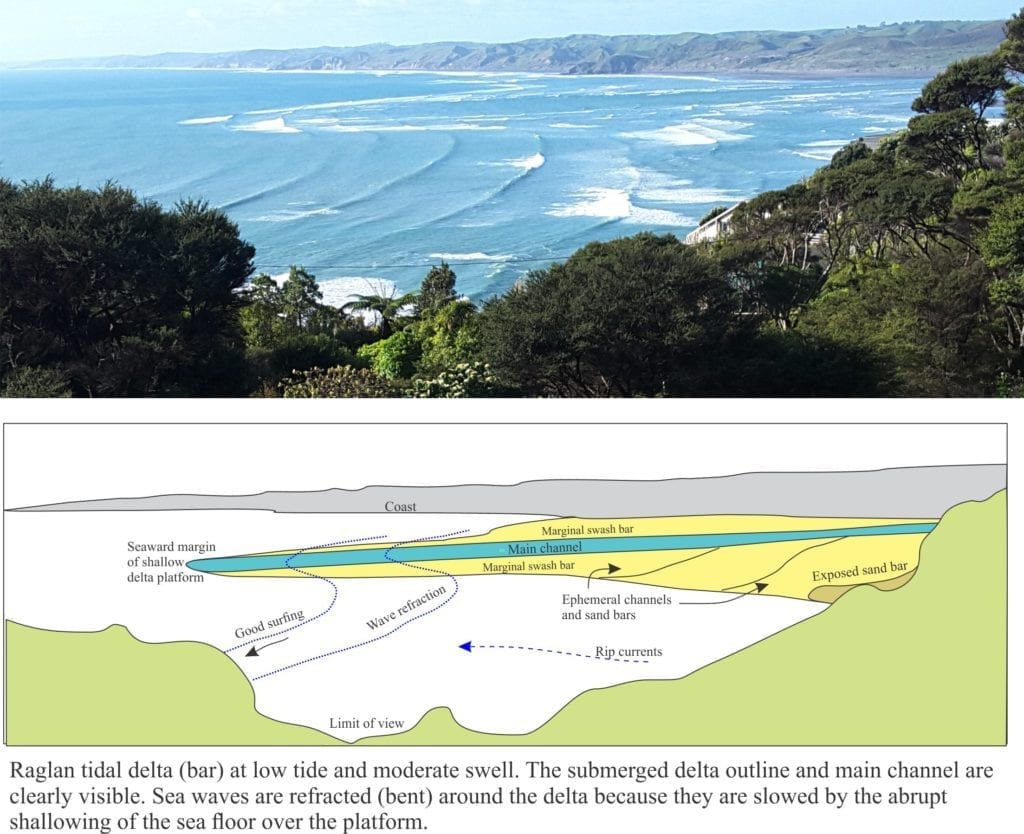

Raglan Harbour is small but it sports a very nice example of a symmetrical ebb tidal delta. The delta extends 1.5 – 2 km from the harbour mouth. Darker hues (image below) that mark the main channel contrast nicely the shallower sand bars on either side over which waves tend to break. These marginal sand deposits are called swash bars.

Westerly swells approach the coast with relatively straight crests. As they pass over the shallow delta platform, they move at a slower speed because they interact (friction) with the sea floor. Some of the wave energy is transferred to the sea floor such that sediment is moved as ripples and dunes. Slowing waves also build in amplitude (height); this is the region where waves break. However, the same waves in the adjacent, deeper water are moving at a faster pace – trace the crests of each wave and you will see it ‘bending’ around the delta.

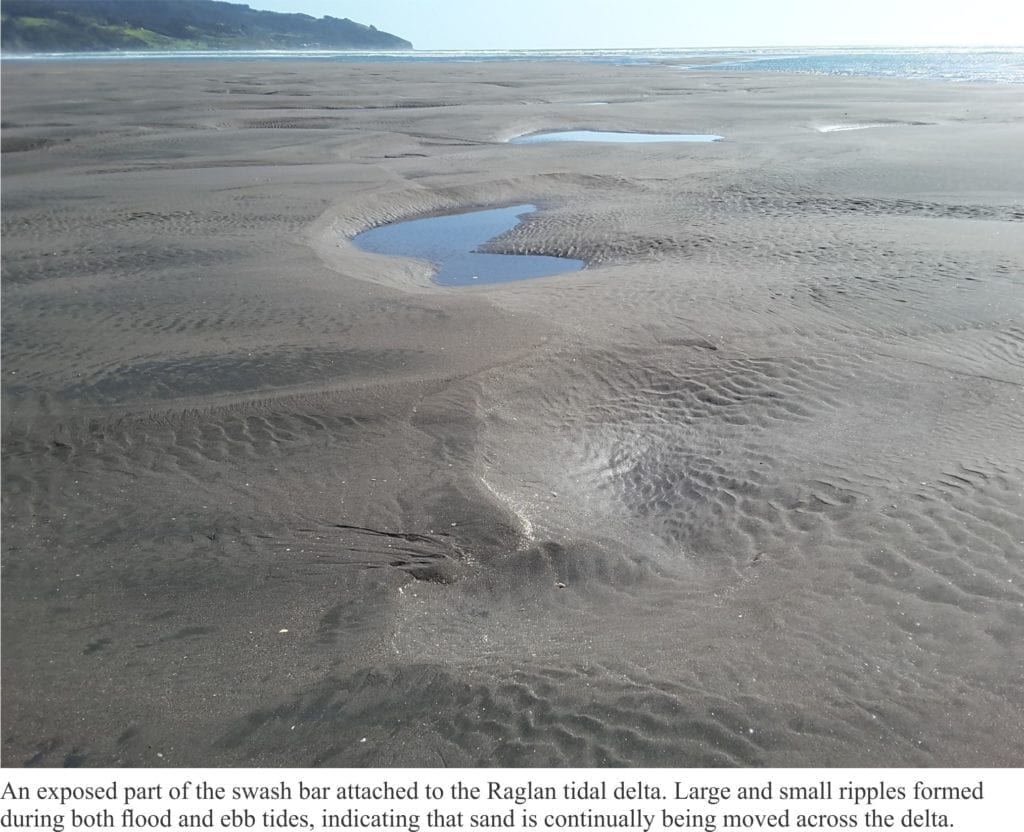

Most of the tidal delta remains submerged even at low tide. Parts of the swash bar that are exposed during low tide show evidence for sand movement, mostly as ripples, large and small. Sand is moved during flood and ebb tides. The shape of these sand bars changes from one tide to the next, demonstrating that this is a dynamic environment.

The Raglan tidal delta consists almost entirely of sand. In contrast, Raglan Harbour and its estuaries contain a high proportion of mud. So where does all that sand come from?

The tidal delta is part of a much larger system of sand transfer – supply and demand from the adjacent continental shelf to the adjacent beaches, shallow sand bars (commonly formed by rip currents) and sand dunes. Sand in the inshore region is also moved along the coast by long-shore currents and it is this sand that continually feeds the delta. The delta in turn, via its main channel, moves sand back onto the shelf, completing the cycle.

The beach south of the tidal delta continually changes its profile. At times the profile is an uninterrupted swath of black sand along most of its length (about 3 km). At other times a significant volume of sand has been removed exposing ancient boulder deposits from nearby Karioi volcano; sand removal frequently occurs during stormy weather. The sand dunes also participate in this budgeting exercise. Sand transfer from the beach (and dunes) is probably a combination of movement directly offshore by rip currents and wave undertow, and long-shore movement towards the delta. Sand replenishment and removal from the beach, and addition to the tidal delta, is part of a much larger system of sand supply and demand – nature’s sand budget.

Sand moved onto the swash bars helps to replace sand that is removed by the deep, fast-moving channel. Channel flows in narrow inlets like the one at Raglan are commonly 4-6 km/hr (1-2 m/second), which may not sound fast (try swimming against it) but is sufficient to move large volumes of sediment during each tidal cycle. There are some small sand bars in the harbour itself, but the channel is an effective flushing mechanism that prevents the estuaries and tidal flats from clogging up.

Changes in sea level have a profound impact on coastal sand systems. If sea level falls, the beach and dunes would follow the retreating shoreline, the harbour would eventually become the domain of non-tidal rivers and swamps, and the main channel would be free to meander over a broad expanse of exposed continental shelf. Tidal deltas might be more ephemeral structures, constantly on the move. This was probably the scenario during the last glaciation, when sea level was more than 100m below its present position.

Perhaps of more immediate concern is a rise in sea level (the present situation) which would erode older foreshore beach and dune deposits, and destabilise some cliff areas south of the Harbour. The Surf Club at the south end of Ngarunui Beach would need to move – yet again. The Harbour area flooded at high tide would increase, resulting in a greater volume of seawater entering and exiting the narrow inlet. To accommodate this, the inlet would need to expand, or the speed of current flow would need to increase. Changes such as these would have an immediate effect on the size and shape of the tidal delta.