This post is part of the How To… series

We introduce some basic hydraulics of sediment movement, bedforms and the concept of Flow Regime.

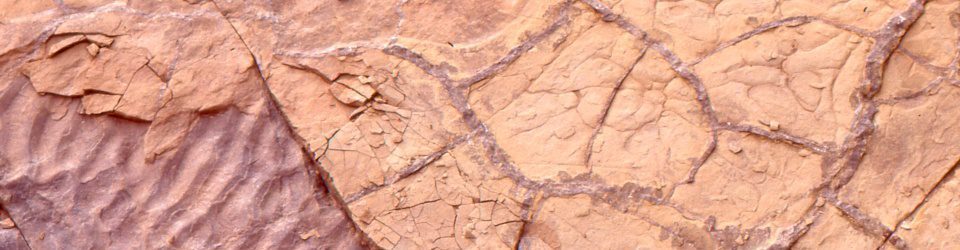

Ripples and dunes form when a fluid (usually water or air) flows across a sediment surface. Structures formed by air flow are called subaerial ripples or dunes; those in water have the qualifier subaqueous. These structures are given the general name bedform. The construction of bedforms requires certain conditions:

– The sand must be cohesionless (i.e. grains do not stick together).

– Flow across the sediment surface must overcome the forces of gravity and friction, and

– There is a critical flow velocity at which grain movement will begin; this also depends on the mass of individual grains, and to some extent their shape.

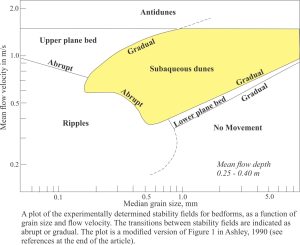

Ripples and dunes form under a relatively limited range of flow conditions. We can illustrate this in a graph of flow velocity against grain size, plotting areas on the graph that correspond to bedform growth. Most of the data for plots like this are derived from flumes where experimental flow conditions can be monitored closely. The plotted distribution shows that bedforms can be categorized according to flow and sediment conditions. This partitioning of bedforms was used to construct the Flow Regime hydraulic model, first published in the now classic 1965 paper by J.C. Harms & R.K. Fahnestock and used widely ever since.

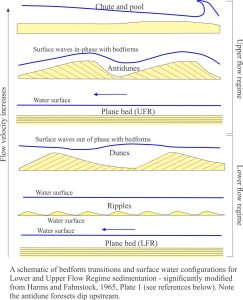

The Flow Regime model considers three fundamentally different states of flow:

- No bed movement where there is too little energy in the system to initiate and maintain sand grain movement,

- A Lower Flow regime in which all common bedforms develop. Here, plane bed (basically parallel, planar laminae with no ripples) represents the lowest velocity, or energy conditions where sediment movement is initiated. It has been observed in flumes and in natural channels that the size of bedforms increases from ripples to large subaqueous dunes in concert with flow velocity. Dune type also changes from two dimensional structures (straight crests and planar crossbed bounding surfaces), to three dimensional structures that have sinuous, arcuate and lunate outlines and spoon or scour-shaped bounding surfaces (commonly seen as trough crossbeds).

- An Upper Flow Regime where the power of stream flow washes out ripples and dunes, replacing them with plane bed (this kind of plane bed commonly has parting lineations), plus antidunes, and erosional chutes and pools.

- As stream flow increases the transition from Lower to Upper flow regime produces one of the more interesting bedforms – antidunes. They are mostly found in shallow channels (e.g. fluvial and tidal channels). You can recognize that this transition has taken place when you see standing surface waves – watch closely and you will see the waves migrate upstream. Antidunes are the bedforms that develop immediately below standing waves (the two are in-phase). If high flow is maintained, the antidunes will also migrate upstream. However, once flow slackens they tend to wash out; the preservation potential of antidunes is low.

The example above shows standing waves in a tidal channel on an out-going tide. Tidal flow is to the left; standing wave migration is to the right (Mangawhai Heads, North Auckland).

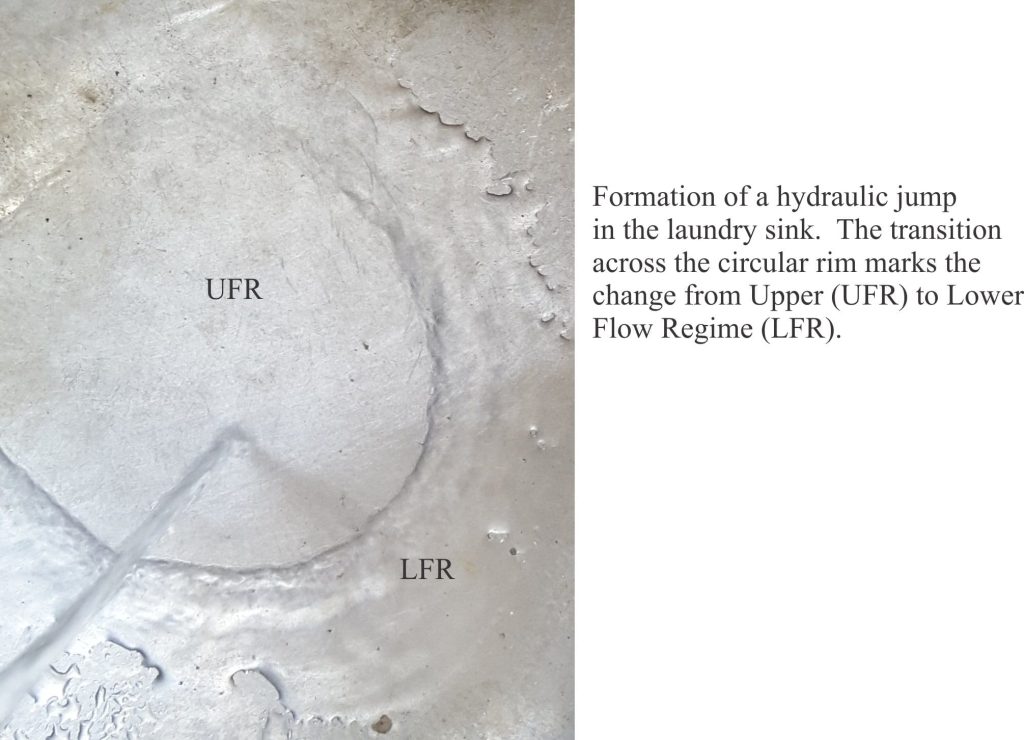

- Hydraulic jumps: The transition from Lower to Upper flow regime passes with a change in bedform, in particular washing out of subaqueous dunes, but there is no sudden break in surface flow – the transition is reasonably smooth. This is not the case for an Upper to Lower flow regime transition that is marked by an abrupt increase in water level and turbulence – a hydraulic jump. Hydraulic jumps can be thought of as standing waves. They are caused by a reduction in Upper Flow Regime velocity, a change in stream-bed gradient or water depth, or combinations of all three.

You can generate a hydraulic jump in your kitchen or laundry sink, so long as the sink floor is reasonably flat. Turn on the tap until you see a flow pattern like the one in the image above. Flat laminar flow is generated by the downward force of tap water – this is the plane bed. The hydraulic jump is located where the flow changes abruptly, with an increase in surface amplitude. Beyond the jump is lower flow regime flow.

We can use the Flow Regime concept in the field as a quantitative indicator of changes in paleoflow in time (i.e stratigraphically) and space (laterally). For example, a stratigraphic sequence that shows a layer of ripples overlain by a layer of trough crossbeds indicates that flow velocities, and hence stream power increased abruptly. What kind of paleoenvironment might this have occurred in? This is one of the central questions for any sedimentological analysis.

Here are a couple of important references:

Ashley, G.M. 1990. Classification of large-scale subaqueous bedforms: A new look at an old problem. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v.60, p. 160-172.

Harms, J.C. and Fahnestock, R.K. 1965. Stratification, bed forms, and flow phenomena (with an example from the Rio Grande). S.E.P.M. Special Publication 12, p. 84-115.

Some more useful posts in this series:

Identifying paleocurrent indicators

Measuring and representing paleocurrents

Crossbedding – some common terminology

Sediment transport: Bedload and suspension load

Fluid flow: Froude and Reynolds numbers

Fluid flow: Shields and Hjulström diagrams