Sunday in Pisa proved to be a welcome change from the usual tourist-cramped, shoulder-barging throngs of popular attractions in Tuscany. No problem finding a seat in a decent café, en route to the Piazza del Miricoli. Cross the street, turn a corner and there – the massive, white-marbled Pisa Duomo, Romanesque grandeur with a veneer of 21st Century scaffolding. But the sense of balance normally attributed to cathedrals, is disrupted by the stand-alone bell tower that leans precariously, like a drunk looking for a lamppost. The Leaning Tower of Pisa has been looking for a lamp-post for almost one thousand years. And for a thousand years, people have been drawn to the tower not because it is particularly beautiful, but because it looks like it is about to fall over. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Tuscany

A measure of the universe; Renaissance slide-rules and Heavenly spheres

Measurement is a cornerstone of science, in fact of pretty well everything we do: How far? How fast? How long? We take most measurement for granted, with little thought to how the process originated. We demand accuracy and precision, forgetting that these are relatively modern luxuries. Before the universal clock chimed GMT in 1884, there were more than 200 time zones in the US. A league in France was shorter than a league in Spain, a discrepancy for which the 16th C French scribe François Rabelais had an imaginative, if rollicking explanation. In his tale, The Life of Gargantua and Pantegruel (1532-1564), a king required a standard distance to be determined (after all, if he was going to send his armies to battle it would be best if his advisors new how far they had to go). He sent a trusted Knight, instructing him to ride to Spain, stopping every league to “roger and swive”; hence the discrepancy. The leagues gradually became longer. The amusing satire of this explanation had its roots in real Medieval measures; the width of a hand, the distance one could walk in an hour. Continue reading

Galileo’s finger

“Their final resting place…” a sepulchral phrase, redolent of a fate that awaits us all. There is no doubt as to its finality, but resting…? A nice metaphor that may convey a sense of comfort to the living, rather than the deceased. Wander through any church or cathedral in Europe and Britain, and you will inevitably walk over cold marble slabs, engraved with the details of those who lie beneath, polished by the feet of a myriad worshipers and tourists. The Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence is, in many respects, like any other magnificent church; it is old, construction beginning in 1295, with alterations and additions during the 14th -15th century overlapping the earlier Gothic forms. The Basilica is stunning, but differs from many of its contemporaries in that it became THE place in Italy to be buried. Continue reading

The life of a Tuscan wall

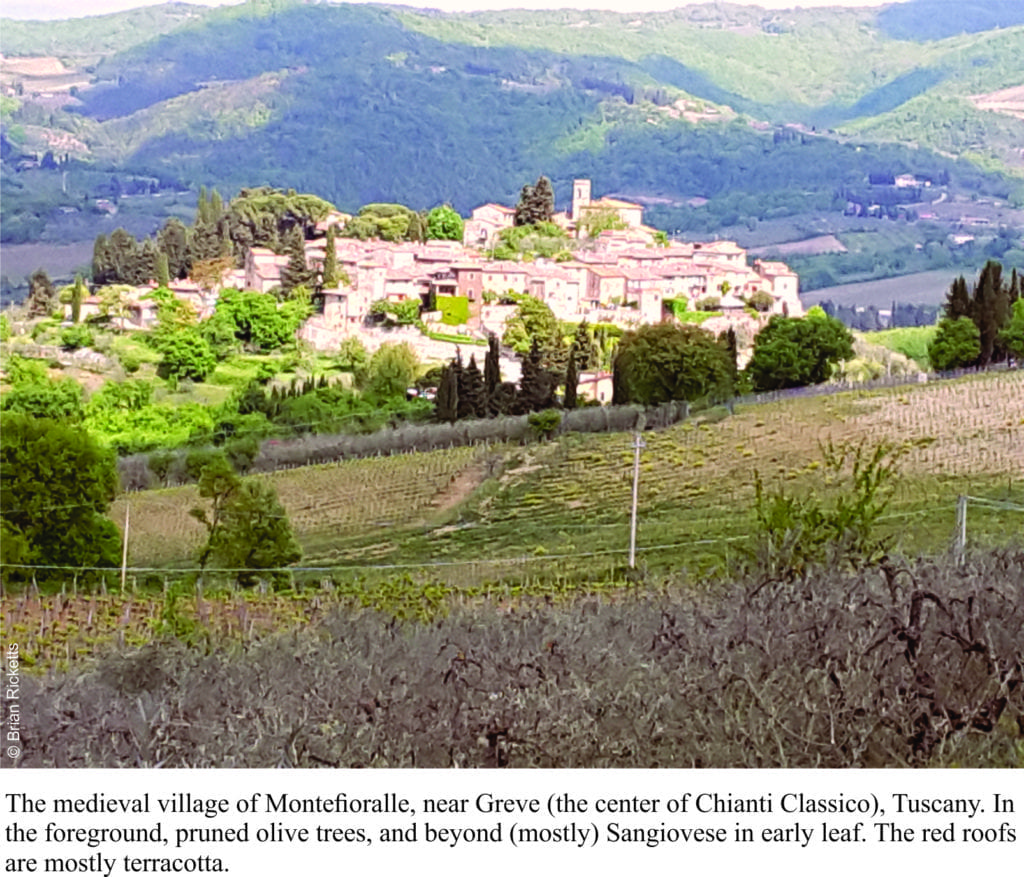

Montefioralle, Chianti country, Tuscany, Italy, and from where I’m sitting (happily sampling a Chianti Classico) I see rolling, wooded hills, next season’s vintage, olive groves, a scattering of farm dwellings, and rock walls. Quintessential Tuscany. Except for a few ratty road cuts, there is little native rock exposed in this part of Tuscany from which a keen geologist might ascertain something of ancient pre-Tuscan history (farther south this changes). But in fact, there are rocks aplenty. Most walls (houses, defensive, retaining, decorative) are made of limestone and sandstone, some quarried and deliberately shaped, as in churches and castello (that date back to the 10th -11th century), and others that made use of whatever was handy at the time. Most of these materials were collected locally; stones that littered the hillsides, and stones brought to the surface during ploughing. Even today, ploughs bring stones to the surface; the local clay-loam soils are incredibly stony (an important part of Chianti terroir).

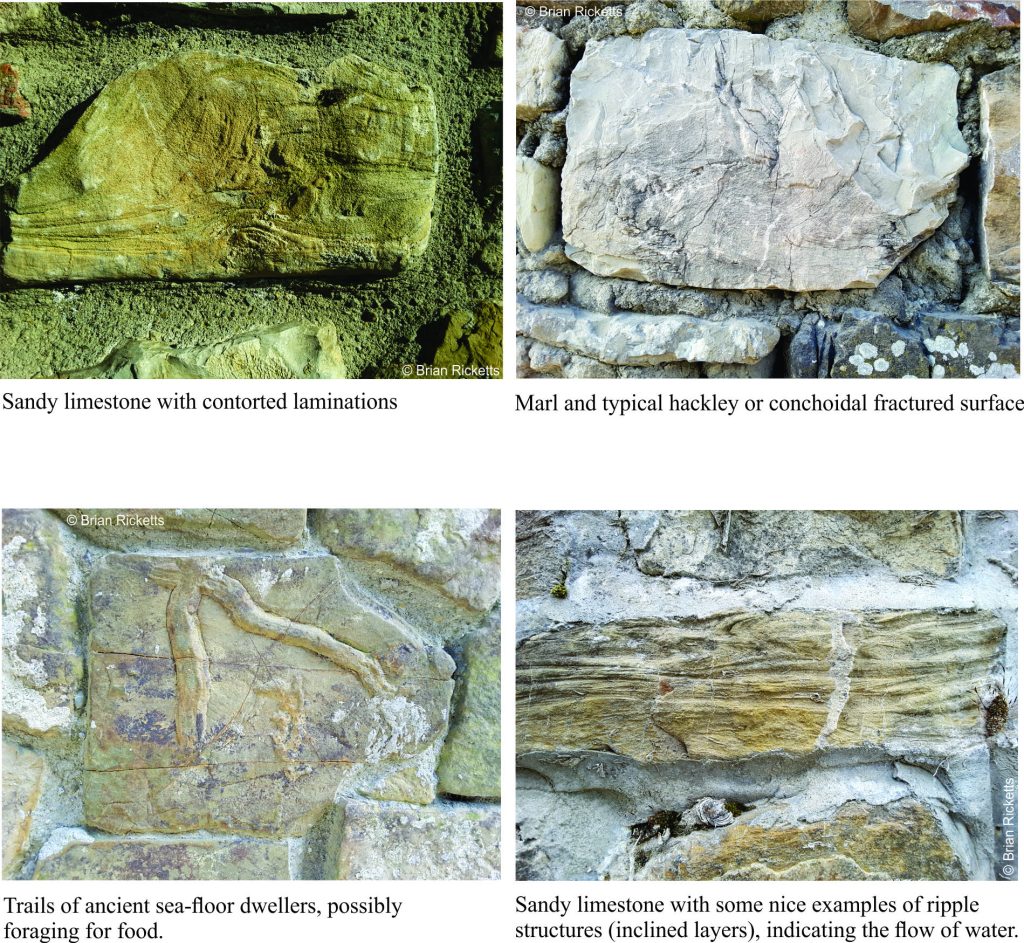

So, despite the paucity of hard-rock exposure, one can make a reasonable guess at the geology beneath the hills and vineyards, based on the stone composition in local buildings. About 50-60% of the stones are cream-coloured marls; marl is an old name (medieval Latin) given to very fine grained, usually muddy limestone that breaks along curved, sharp-edged surfaces (referred to as conchoidal breakage). The Tuscan marls are very hard – ideal for building stone. Variations on this theme include sandy limestones, some of which contain intricate contorted layering, and small crossbeds that indicate flowing water many millions of years ago.

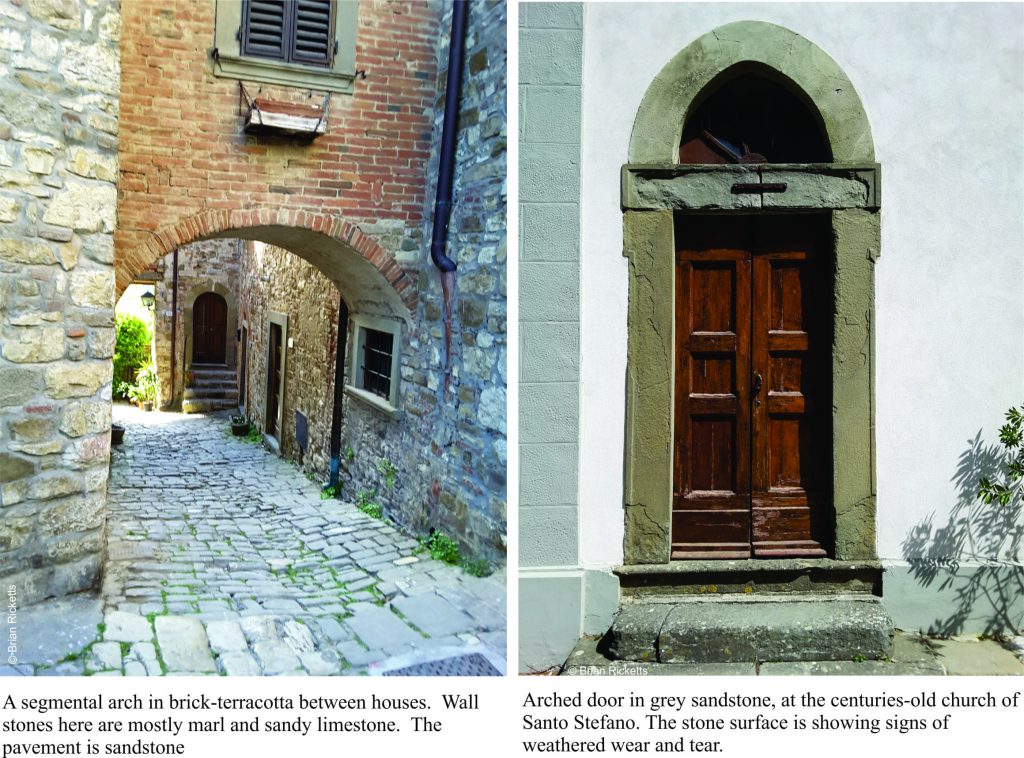

Grey sandstone is also common; in fact it is found as paving stone throughout most of Tuscany. All kinds of structures are visible in these stones, especially cut stones in larger buildings and roads; fossil ripples that indicate flowing water, trails and burrows of critters that moved across or below the ancient seafloor in search of food or finding a place to live. Some of the sandstones are not as hard as the marls, and in places show quite advanced damage where bits of rock fritter away with the vagaries of weather.

An assortment of red bricks, some rumoured to be of Roman or Etruscan derivation, has been used in most walls. It looks like odd-shaped bricks are filling equally odd-shaped gaps, but they have also been used to replace stone arches over doors, or fill holes in walls left by marauding armies (of which there were many), or neglect.

The rocks were originally deposited as sediment in an ancient and vast ocean called Tethys, that separated two supercontinents – Gondwana, and Laurasia (most of Europe and Asia). The Tethys was closed when, about 65 million years ago, the African plate (part of Gondwana) drifted north and crunched into Laurasia. The resulting uplift produced the Apennine Ranges that now course the length of Italy.

Montefioralle is a picturesque hill-top village, typical of many in Tuscany. Its medieval origins are still visible, but frequent battles between neighbouring villages, as well as larger fracas between Florence and Siena, put a few dents in the outer wall and houses. The hill top is crowned by a small church and tower; the last refuge in the event of siege. There is clear evidence of repairs made over the last 800 plus years, including, I suspect, some from a more recent European conflict.

Stones in these Tuscan walls weave their tales in different threads. The limestones and sandstones have a geological story that spans 10s of millions of years, the disappearance of an ocean and the collision of continents. Each stone and brick can also relate centuries of local history; each was carefully placed by someone, a stone-mason or perhaps a Renaissance DIY. Nameless, we can admire their handy-work, wonder what they talked about with their fellow workers, what they ate, who they loved. There are centuries of these former lives everywhere in Tuscany. Chianti Classico loosens all their tongues.