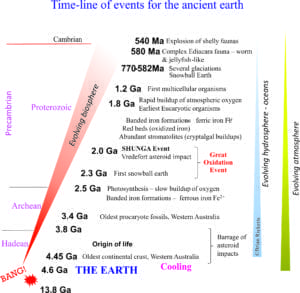

Stromatolites. The Precambrian is replete with them. In many ways they define the Precambrian, that period of earth history, about 90% of it, that set the scene for the world we currently live in – its atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, and biosphere. It’s the period when life began more than 3.4 billion years ago, taking its time (about 3 billion years) to get over that first rush of DNA replication.

The Atlas, as are all blogs, is a publication. If you use the images, please acknowledge their source (it is the polite, and professional thing to do).

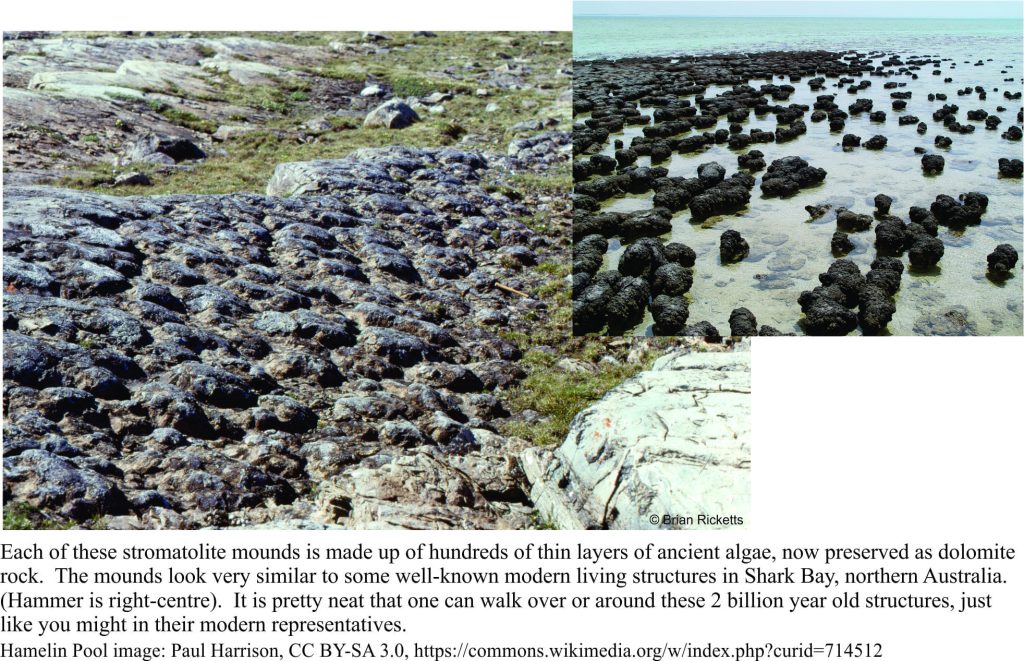

Stromatolites are the sedimentary record of that really prolonged period of geological time. Some of the oldest known, bona fide cryptalgal structures are found in the 3.4 Ga North Pole deposits. They represent fossil slime – mats of photosynthetic, prokaryotic cyanobacteria. They were responsible for producing the oxygen we, and most other life forms breath.

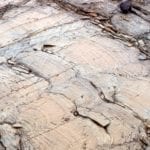

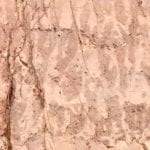

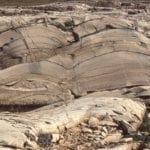

Stromatolites really came into their own by about 2.5Ga, forming extensive buildups, and reef-like structures, by slow, incremental addition, mat-by-mat, in the ancient shallow seas. Growth habits varied from broad flat domes to intricately branched columns. Stromatolite structure, shape and distribution were primarily controlled by environmental conditions such as water depth, wave and current energy, and substrate (muddy, sandy). Glacially polished rock outcrops on Belcher Islands (where all the following images are from) show these structures in exquisite detail.

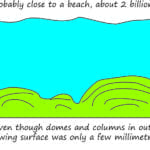

Stromatolites in outcrop commonly appear huge, as columns or domes extending vertically several metres. But their sea floor profiles, or synoptic relief during growth was low. We can visualize this when tracing individual laminae or sets of laminae (ie. the original mat surface) from one column to the next. Your average shallow shelf or platform stromatolite extended no more than a few millimeters or centimeters above the sea floor. Some large mounds, or reef-like structures had a few metres relief; but nothing like more recent coral reefs. This also means that the environmental conditions for incremental growth must have been stable for long periods of time. This needs to be kept in mind when looking at cryptalgal structures in outcrop; their apparent size can be misleading.

Check out this post for outcrop descriptions of stromatolite morphological features

This link will take you to an explanation of the Atlas series, the ownership, use and acknowledgment of images. There, you will also find links to the other categories.

Click on the image for an expanded view, then ‘back page’ arrow to return to the Atlas.

A few publications that have a bearing on the set of images below:

Ricketts, B.D. 1983: The evolution of a Middle Precambrian dolostone sequence – a spectrum of dolomitization regimes; Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v. 53, p. 565-596.

Ricketts, B.D. and Donaldson, J.A. 1981: Sedimentary history of the Belcher Group of Hudson Bay; Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 81-10, p. 235-254. F.A.H. Campbell, Editor

Ricketts, B.D. and Donaldson, J.A. 1989: Stromatolite reef development on a mud-dominated platform in the Middle Precambrian Belcher Group of Hudson Bay; Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir 13, p. 113-119.

Donaldson, J.A. and Ricketts, B.D. 1979: Beachrock in Proterozoic dolostone of the Belcher Islands, Northwest Territories; Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v. 49, p. 1287-1294.

The images:

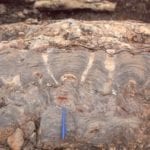

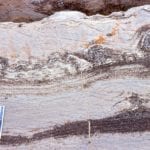

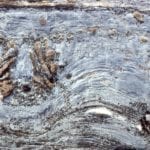

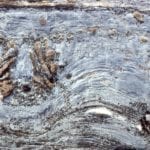

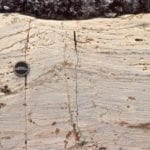

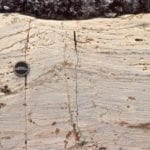

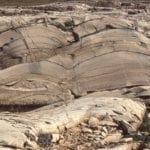

Bulbous, dolomitized stromatolites in the lower part of the outcrop become progressively more branched towards the top. The view is oblique to bedding; the surface polished by Laurentide glacial ice. McLeary Fm. Right: dashes follow the synoptic surface, which approximates the actual growing mat morphology and relief at the sea floor. Whereas the stromatolites in outcrop appear large, at the time of growth (2 billion years ago) the sea floor would have looked vaguely dimpled or domed. Bedding-parallel stylolites have thinned the rock sequence by 10-20%.

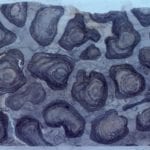

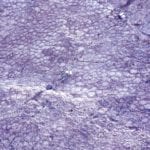

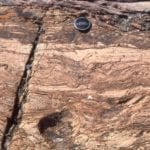

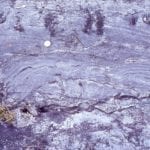

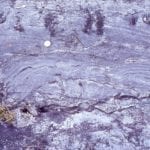

Bulbous stromatolites similar to those shown above. The original carbonate (calcite-high Mg calcite-aragonite) has been completely replaced by dolomite. Some of the upstanding, resistant edges are subsequent chert replacement. Image on the right shows excellent preservation of original laminae that in some cases can be traced across 2 and 3 branches. Both are oblique to bedding. McLeary Fm. Intercolumn sediment is dolomitized carbonate mud.

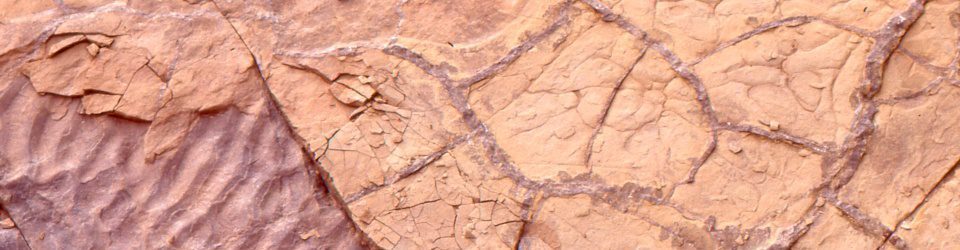

Large, closely-spaced, low relief stromatolite domes; synoptic relief was 5-8cm. Look closely at the laminae and in some you will see continuity from one dome to another, and in others discontinuities and overlaps 2-4 laminae thick. Mavor Fm.

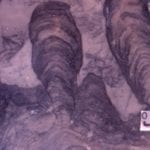

This distinctive stromatolite unit can be traced 10s of kilometres. Closely spaced vertical, digitate columns grew on a shallow subtidal platform. Columns are relatively uniform width, usually branched, with tangential laminae forming a sturdy wall. Synoptic relief was only a few millimetres. McLeary Fm.

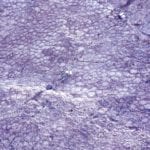

Polished slabs of the digitate stromatolites shown above. The scale on the right is centimetres. Preserved laminae are mm to sub-mm thick. The rock has been completely dolmitized, and yet delicate structure is preserved. McLeary Fm.

Digitate stromatolite columns in cross-section (left) and bedding (right). Dolomitiztion here has produced coarse crystalline textures that have partly obliterated outlines and laminae. Mavor Fm.

Domal, digitate, and coalescing stromatolite columns, growth habits that changed with environmental conditions or interruptions in growth (e.g. storms), McLeary Fm. Image on right has an erosional discordance at the pen tip. branching began during mat regrowth.

Radiating, digitate, branching columns. Left: the radiating cluster is a solitary buildup in surrounding flat, laminated mats. Right: The digitate cluster has been disrupted and partly eroded by crossbedded sandstone, indicating a significant change in local environmental conditions (shallow subtidal to intertidal).

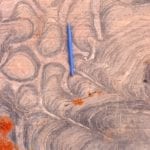

Wavy mats give way to columnar stromatolites with cone-shaped laminae. This form has historically been called Conophyton. McLeary fm.

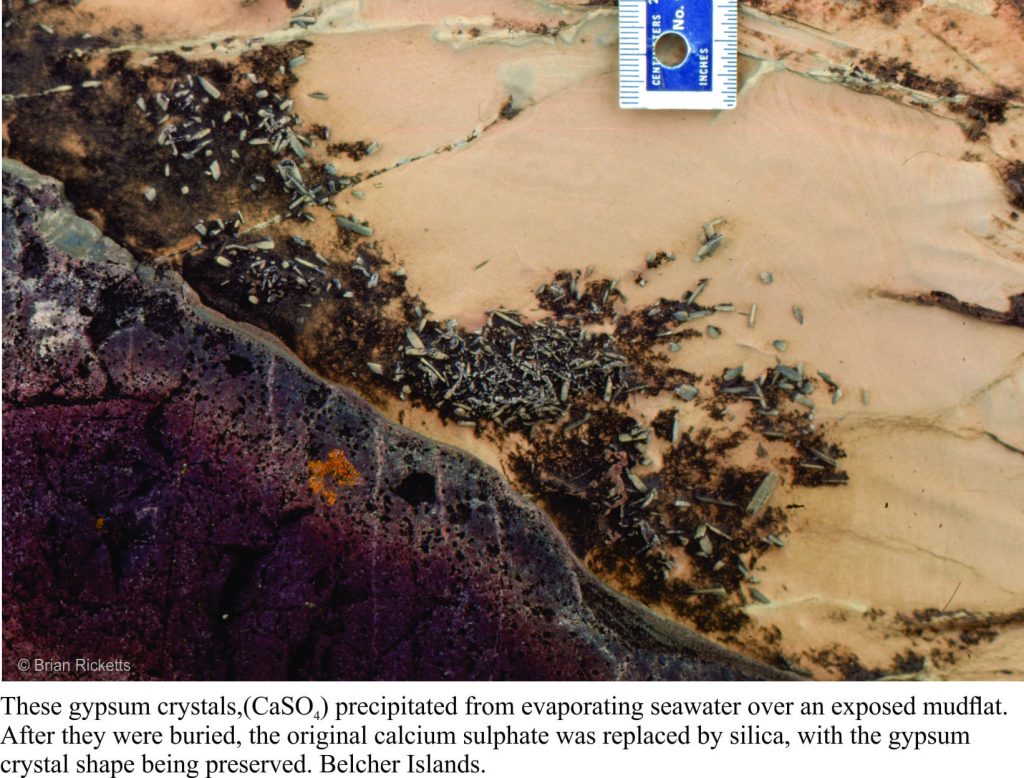

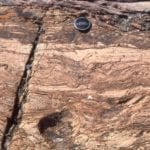

Left: Dolomite pseudomorphs of gypsum in dolarenite. Right: Fine-grained dolarenites interbedded with carbonate mudstone (dolomite) and simple, laminated crpytalgal mats (partly silicified). Gypsum psuedomorphs (spots) are scattered throughout. A layer of algal mat and mud rip-ups is present at the lens cap. McLeary Fm.

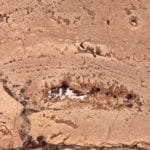

Beachrock is common in the McLeary Fm. Here, a block of dislodged beachrock (preferentially cemented dolomitic sandstone) has been overturned, as evidenced by the small, upside-down stromatolite columns.

Subtidal to outer platform stromatolite mounds that have undergone more intense recrystallization during dolomite replacement of the original carbonate, such that original column-bulb outlines are partly obscured. Remnants of small columns are visible in the upper dome layers (right). There is a hint of coloumn or mat detachment, and possibly pisoliths in the centre. The vugs are secondary diagenetic features from dissolution of (?) sparry calcite and dolomite replacement. Tukarak Fm (immediately overlies the McLeary Fm).

Recrystallized, dolomitic mounds where the original carbonate has been replaced by one or two generations of dolomite spar. The void is lined with late diagenetic dolomite spar, and even later calcite (white crystals). Tukarak Fm.

Microdigitate mats, here associated with grainstone. Left: mats above the dark cherty layer show at least three stages of growth, each following an episode of erosion. Mats below the chert are more simple wavy forms. The grainstone above contains numerous mud and mat rip-ups. Right: Slightly larger, but no less delicate microdigitate mats and columns, again showing evidence of erosion and regrowth. Both examples formed in intertidal to supratidal flats. McLeary Fm.

Left: Small dome, beginning with flat laminae at the base, and successions of microdigitate columns above. Right: Small domes capped by microdigitate columns. Laminated mudstone above are discordant and eroded. The white, silicified masses were probably larger domal structures. McLeary Fm.

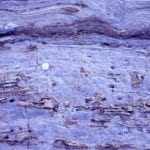

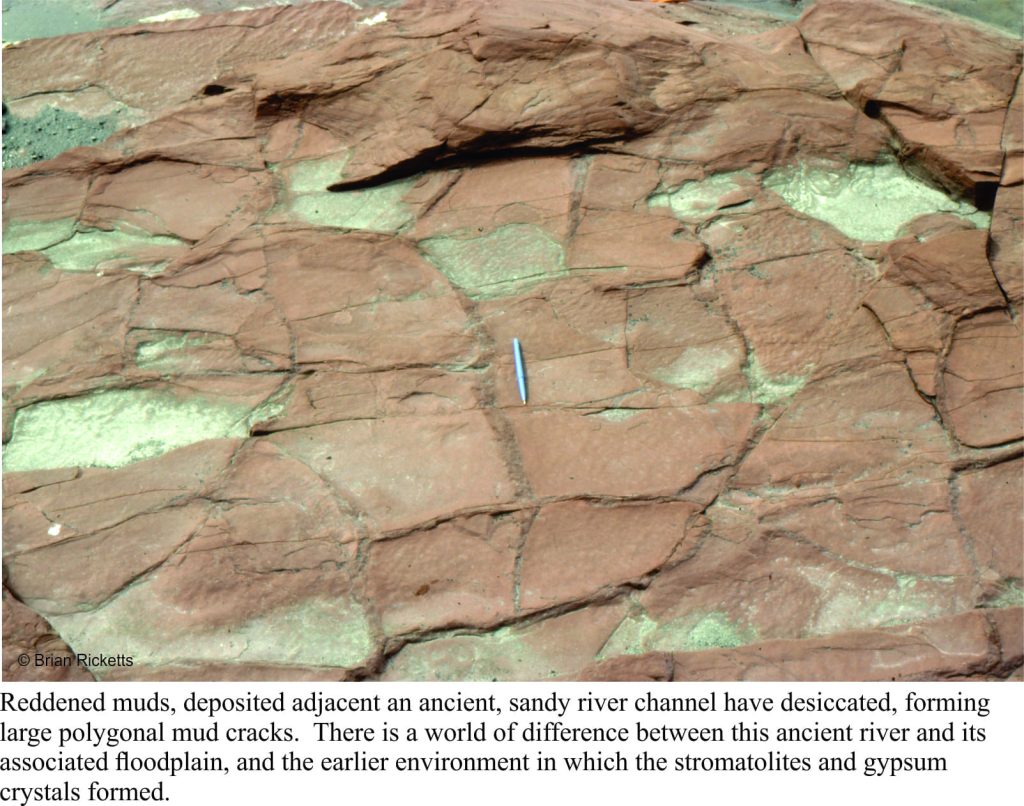

Both images show wavy mats and microdigitate columns, disrupted by supratidal desiccation, storm-loading pull-aparts, and fragmentation. The interval in the left image is capped by larger domal masses that in turn have been locally overturned. McLeary Fm.

Left: View approximately along strike. Second-order mounds are nicely exposed here (by the hammer). Right: View is slightly oblique to depositional dip. Here too we can see smaller mounds superposed on the larger structure. Mavor Fm.

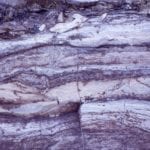

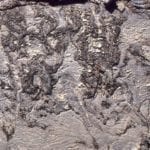

Detail of the wavy and crinkley cryptalgal laminae, through a (2nd order) mound crest (left) and trough (right). The synoptic relief on any lamination is rarely more than a centimetre.