Angle of repose: The natural slope of loose, cohesionless sedimentary particles (sand, gravel) under static conditions, as a function of gravity and friction forces. In dry sand the angle is 34°. In water saturated sand where friction is reduced, the angle is 15° to 30°.

Anisotropic HCS: Applies to hummocky cross-stratification where the geometry and dip of laminae change for profiles viewed at different orientations of the same hummock. Cf. isotropic HCS.

Antidunes: Bedforms that develop in Upper Flow Regime, Froude supercritical flow. The corresponding stationary (surface) waves are in-phase with the bedforms. Unlike ripples, the accreting bedform face grows upstream – antidunes migrate upstream in concert with deposition on the stoss face. When flow conditions wane, they become unstable and wash out or surge downstream. Their preservation potential is low.

Armoured mud balls: A coarse-grained carapace that adheres to cohesive mud rip-up clasts that are rolled across a bed of sand and pebbles.

Asymmetric ripples Ripples that have a distinct lee slope that is steeper than the adjacent stoss slope. This is the most common ripple type formed in unidirectional and bidirectional flows.

Avalanche face: The downstream-facing part of a ripple or dune bedform where sediment carried up the stoss face tumbles under the influence of gravity down the lee face.

Backflow: Flow on the lee side of bedforms that is opposite the overall direction of flow. Backflow may be strong enough to form small-scale beforms (commonly ripples) that migrate up the main bedform lee face or upstream.

Backwash: Water that completes its run-up across a beach (swash) and returns to the wave-surf zone. Flow velocities are determined primarily by the gravity component imposed by the beach gradient.

Ball and pillow structure: Ball, or spheroidal shaped structures formed by soft sediment deformation of sandstone crossbeds during early differential compaction, that is promoted by sediment dewatering. The original cross laminations are folded, oversteepened, and even overturned. They are common in fluvial deposits.

Bank-full conditions The point at which the water level in a river channel reaches the top of the bank, beyond which water spills over the floodplain.

Beachrock: Rapidly cemented carbonate and siliciclastic sand-gravel across a beach face; cementation occurs at or just beneath the surface. Cementation rates are measured in months. Once lithified, they can be eroded by storms into boulder deposits, that can then be re-cemented. Rapid lithification of beach sand-gravel changes the habitat for local benthic organisms. Cements are mostly aragonite and high magnesium calcite.

Bed: The preeminent unit in sedimentary geology and stratigraphy, that represents a period of relatively uninterrupted deposition – the duration can range from seconds to multiple years. Sediment composition and texture are relatively uniform within a single bed but can vary between beds. Beds are bound top and bottom by bedding planes. Their areal extent can exceed many 10s of square kilometres and be as little as a few decimetres. Thicknesses also vary greatly, from a few millimetres to 10s of metres.

Bedding plane: The bounding surfaces of beds. The upper plane represents cessation of the depositional event that was responsible for creating the bed. If erosion of the upper bedding plane occurs, it is usually associated with the next depositional event. Differential compaction by overlying beds can also change the form of the bedding plane. The lower bedding plane coincides with the top of the underlying bed. The geometry of the bedding planes defines styles of bedding such as parallel bedding, lenticular bedding, wedge-shaped bedding.

Bedform: Sedimentary structures produced by bedload transport of loose, non-cohesive sediment. Typically manifested as ripple and dune-like structures.

Bedload: Loose or non-cohesive sediment particles (silt, sand, gravel – sizes) at the sediment-water or sediment-air interface, that will move along the bed if fluid flow velocities exceed the threshold velocity. The bedload consists of a traction carpet, and a suspension load.

Bioturbation: The general term for the activity of organisms that live on and within sediment. During the course of scavenging, grazing and burrowing for food, constructing a home, travelling from one place to another, or escaping predation or burial, these critters produce traces that reflect the type of sediment and the behavioural activity of the organisms. Intense bioturbation may destroy primary sedimentary structures like and bedforms.

Bouma sequence: Named after Arnold Bouma, one of the first to recognise the repetitive sedimentological organisation of turbidites. Bouma sequences represent individual turbidity current flow units, whether the sequence is complete or truncated. A complete sequence contains 5 divisions, becoming progressively finer-grained towards the top; some divisions may not develop:

- Massive muddy sandstone, with or without a scoured base.

- Graded and laminated muddy sandstone.

- Laminated with ripples and climbing ripples, commonly convoluted by soft sediment deformation.

- Graded, laminated siltstone-mudstone.

- A mix of turbidity current mud and hemipelagic mud, that are deposited from suspension.

Boundary layer (granular): Also called a no slip or zero shear stress boundary. The contact between a flowing fluid and a solid surface is defined by a boundary layer where friction forces reduce flow velocity to zero. A velocity profile through the boundary layer shows a gradual increase in velocity to the point where free stream flow prevails. Flow along boundary layers is either laminar or turbulent depending on the Reynolds number.

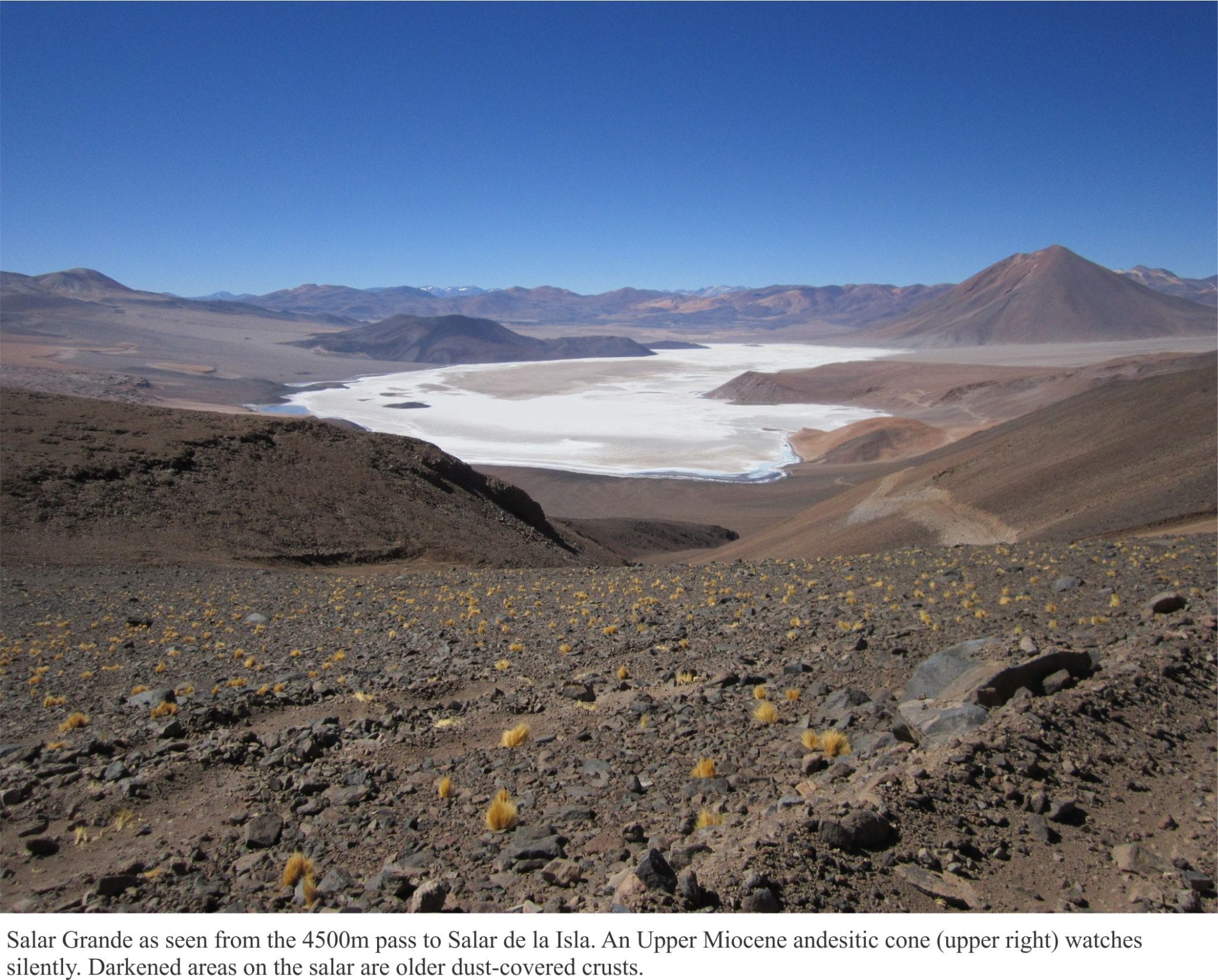

Caliche: Also called calcrete. Soil horizons in which carbonate precipitation results in a hardened crust. They develop in regions in which evaporation exceed precipitation, where periods of wetting alternate with drying. Thus, carbonate textures commonly show evidence of dissolution and reprecipitation. A common product is vadose pisoids that also show evidence of multiple episodes of dissolution and precipitation. They can develop in alluvial-lacustrine and intertidal-supratidal settings.

Catenary ripples These are similar to lunate ripples but in this case have connected crest lines concave downstream, and less slopes on the concave slopes. They may be transitional forms to lunate ripples.

Chute and pool Chute and pool conditions usually develop at flow velocities higher than those responsible for unstable antidunes. Chute and pool morphology is centred on a hydraulic jump – upstream flow in the chute is supercritical, and immediately downstream flow is subcritical (the pool). Chutes and pools can also migrate upstream which means the hydraulic jump moves in tandem.

Clast-supported framework: This term applies to granular rocks where clasts are mostly in contact with one another. It usually refers to lithologies containing clasts that are sand sized and larger; it does not apply to mudstones or siltstones because it is difficult or impossible to distinguish framework from matrix. This textural property applies to siliciclastics and carbonates. Cf. matrix-supported framework.

Climbing ripples Also called ripple drift. A typical climbing ripple profile is manifested as ripple crossbed sets migrating over the upstream, or stoss face of earlier-formed ripples. Ripples can be symmetric or asymmetric. They form where there is a combination of bedload and suspended load deposition of fine-grained sand. Climbing ripples are one of the few bedforms that preserve stoss-side laminae. They tend to form where high suspension sediment loads and unidirectional flow are combined, for example rivers in flood, and turbidity currents.

Coarse-tail grading: The vertical trend in maximum clast size at successively higher levels within a bed or flow unit. The trend is identified with only the coarse-tail of a grain-size distribution curve. It is common in the A divisions of Bouma sequences.

Cohesionless grains: Grains (usually sand or silt) that do not stick together. This property is necessary for most sandy bedforms to form. Cohesion in finer grained particles prevents the formation of sediment bedload and saltation load movement.

Conglomerate: Sedimentary rock where the framework consists of clasts coarser than 2 mm (granule). Clasts show variable degrees of rounding and shape. Sorting tends to be poor. The term gravel is used for modern sediments. They typically represent high energy conditions like those found in braided rivers, alluvial fans, and gravel beaches. Cf. breccia, pebbly mudstone.

Convoluted laminae: Laminae that are initially parallel or crossbedded, will become folded and pulled apart during the early stages of compaction (soon after deposition) and dewatering. They are characteristic of turbidites where dewatering is hindered by muddy permeability barriers, such that local fluid pressures are elevated. They are also common in fluvial and other channelised sediments (here called ball and pillow structures).

Coprolite: Fossil faeces. Large lumps commonly egg- or mound-shaped., Although rare, they have been described from Mesozoic dinosaur-bearing beds. Pelloidal textures are usually sand-sized and frequently replaced by glauconite or phosphate – many are interpreted as faecal pellets.

Coquina: A limestone made up of shells, shell fragments and other bioclasts, with a degree of sorting that indicates relatively high depositional energy. Where the fragments are mostly sand-sized, the Dunham limestone classification equivalent is grainstone.

Coralline algae: Calcite and high magnesium calcite precipitating red algae, that build upon substrates such as bioclasts and rock surfaces and other algae. All begin life as encrusters, but grow to different forms such as articulated branches, or nodular clusters around shells or pebbles (e.g. Lithothamnion). They are an important contributor to cool-water bioclastic limestones.

Crawling traces: (Trace fossils) A behavioural trait exhibited by invertebrates that produce trails, grooves and burrows when moving from A to B – basically just getting somewhere. Traces are fairly simple, lacking systematic patterns.

Crevasse splay: A crudely fan-shaped body of sediment deposited on the flood plain when a river in flood breaks through its levee. The sediment is mostly fine sand and silt. Ripples and climbing ripples tend to form close to the levee breach where flow velocities are highest; erosional discordances are also common. Flow competence wanes rapidly as the flood waters splay across the floodplain, depositing progressively finer-grained sediment.

Crossbed: Refers to the dipping cross stratification, or foresets of bedforms like ripples and sandwaves. In subcritical flow, foresets dip in the direction of flow (air, water).

Cryptalgal laminates: A general term for laminated mats composed primarily of cyanobacteria, but like includes other microbes. The laminates may be flat and uniform, or tufted, pustulose, or polygonal, resulting from desiccation or, in arid environments, evaporite precipitation. In the rock record they are commonly found with stromatolites. The term microbialite is generally used in modern examples because there are several groups of microbes including bacteria, cycanobacteria, and red and green algae.

Cut bank: An outside river bank subjected to erosion. In meandering fluvial channels, cut banks are located opposite point bars (the inside channel margin on which deposition occurs). Channels tend to be deepest along the cut bank margin.

Cyclic steps Cyclic steps are basically trains of chutes and pools, where supercritical to subcritical transitions occur repeatedly downstream. At each transition there is a hydraulic jump – this is the step in each flow transition. As the hydraulic jumps move upstream they erode sediment that is then deposited on the stoss face immediately downstream. The wavelength of cyclic steps is potentially 100-500 times the water depth, and is significantly greater than that for stationary waves and their associated antidunes.

2-D bedforms: Ripple and dune bedforms that have straight crests. Commonly associated with tabular crossbedding.

3-D bedforms: Ripples and dunes that have sinuous, cuspate, lunate, or linguoid crests.

Debris flow: A variety of sediment gravity flow containing highly variable proportions of mud, sand, and gravel, in which the two primary mechanisms for maintaining clast support are (mud) matrix strength and clast collisions. Unlike turbidites, there is no turbulence, hence normal grading is poor. Some debris flows develop significant internal shear that imparts a crude stratification and/or an alignment of clasts. Terrestrial flows include highly mobile mud flows, and lahars in volcanic terrains.

Desiccation cracks: Polygonal fracture patterns that develop across the surface of drying mud surfaces. Also called mud cracks. The cracks will be filled by sediment during subsequent flooding. Desiccation polygons are also prone to erosion and break-up during subsequent inundation. They can form almost anywhere that muddy sediment is subaerially exposed.

Dike/dyke (geomorphology): (Dike = North American; Dyke = English). Another term for either natural or engineered levee, berm or embankment along the banks of rivers or sea shores to help prevent flooding.

Dike/dyke (sedimentary): (Dike = North American; Dyke = English) Sheet-like feeders of sediment – commonly a mix of mud, sand, brecciated host rock, that have been forced through sedimentary strata at a high angle to layering. Driving mechanisms are commonly transient elevated fluid pressures generated by compaction or seismicity.

Dish structures: During early compaction and dewatering, fluid that escapes via vertical pillars and sheets will disrupt primary laminae, and in many cases remove fine matrix. The resulting structures are dish-shaped, concave upwards sand laminae. They are common in laminated sandstones that have vertical permeability gradients.

Distribution grading: Another, perhaps more sensible name for normal grading. See graded bedding.

Draa: The largest aeolian dune bedform that can be as high as 300 m and several kilometres long. They are usually compound structures consisting of smaller, amalgamated and superposed aeolian bedforms. Classic examples are found in the Sahara Desert. They are also found on Mars. Named after Draa Valley in Morocco.

Drop stone: Another name for rafted clast, carried by floating tree roots, seaweed, and ice, eventually released and deposited, commonly far from its original source. Large clasts may cause impact folds on the sediment surface, particularly if deposited in fine-grained sediment. Compaction drapes may also develop over upper surface of the clast.

Dune: The general name for large ripple-like bedforms. Commonly associated with aeolian structures (sand dune, dune sea, coastal dunes), but also applies to subaqueous structures (subaqueous dunes) that commonly form in sandy fluvial systems and sandy shelves or platforms influenced by tides. cf. antidune.

Dwelling traces: (Trace fossils) Mostly expressed as burrows and borings produced by invertebrates for somewhere to live. Commonly built by suspension feeders.

Edgewise conglomerate: Conglomerate composed of platy or bladed clasts, such as shale fragments, ripped-up carbonate hardground slabs, or shells that are stacked on edge and packed into crude radial patterns. Their formation requires relatively high energy (as well as an abundant supply of clasts). They tend to form on wave-washed beaches and can extend laterally as pavements for many metres.

Feeding trails: (Trace fossils) (Fodichnia) These trails are constructed by deposit feeders on or beneath the sediment surface. They tend to reflect regular patterns of the search for food. Zoophycus is an excellent example expressed as a corkscrew-like, arcuate pattern of spreiten around a central cylindrical burrow.

Flaser bedding: Sandy deposits in which ripples are draped by muddy veneers, or flasers. They are common across mixed sand-mud tidal flats. The ripples form during one stage of tidal flow; the mud drapes during the opposite flow. They commonly occur with lenticular bedded ripples. Together they provide good evidence for tidal current asymmetry.

Flow separation: Stream flow along a ripple or dune stoss face results in bedload movement of sediment. Downstream of the brink point this flow separates from the bedform over the trough; flow re-attaches on the stoss face downstream. Separated flow forms eddies and local backflow (reverse flow) in the trough. Flow separation allows sediment to avalanche down the lee face.

Flute casts: Tapered, scoop-shaped scours on sediment surfaces that are subsequently filled with sediment and exposed as casts at the base of the overlying bed. The tapered end points in the direction of flow, or paleoflow; flute casts provide unambiguous paleocurrent directions. The original scour may have been initiated by turbulent eddies, or erosion down-flow of small objects like pebbles, mud rip-ups, and fossils. They are common at the base of turbidites, and frequently accompany other sole marks like groove casts and skip marks.

Foredune: Sand dunes that line ocean, lagoon, estuarine, sandspit and barrier island, and lacustrine coasts. In marine settings they occupy the zone above high or spring tide. They usually contain sand of the same composition as the beach. They form an important part of a budget system that sees sand moved into and out of the dune-beach and adjacent shoreface.

Foreset: Dipping, closely spaced stratification that define crossbeds. Normally seen in cross-section profile views of bedforms where they represent the lee face of ripples and larger dune structures. Foresets dip in the direction of flow and bedform migration. Foresets develop as grains move from the bedform stoss face and avalanche down the lee face. Forest geometry at the lower bounding surface is either abrupt or tangential. The geometry at upper bounding surfaces is commonly abrupt because of erosion beneath the overlying forest unit.

Frost heave: Soil of bedrock that is pushed towards the surface by the expansion of ice as it freezes. Heave can result in general mounding of saturated soils or sediment, or the pushing upward of blocks of rock bound by fractures or joints. This process can create significant damage to building foundations. It is a common periglacial phenomenon.

Gilbert delta: Originally described by G. Gilbert for coarse-grained deltas that display a 3-fold architecture: horizontal to shallow dipping topset beds (analogous to a delta plain), foresets beds, and bottom set beds. They form where coarse bedload rivers empty into lakes and marine basins. They are included in the general category of fan deltas.

Glacial striae: Grooves and scratches produced by ice-drag of rocky clasts over a subglacial bedrock surface. Measurement of striae bearings provides useful information on ice flow directions.

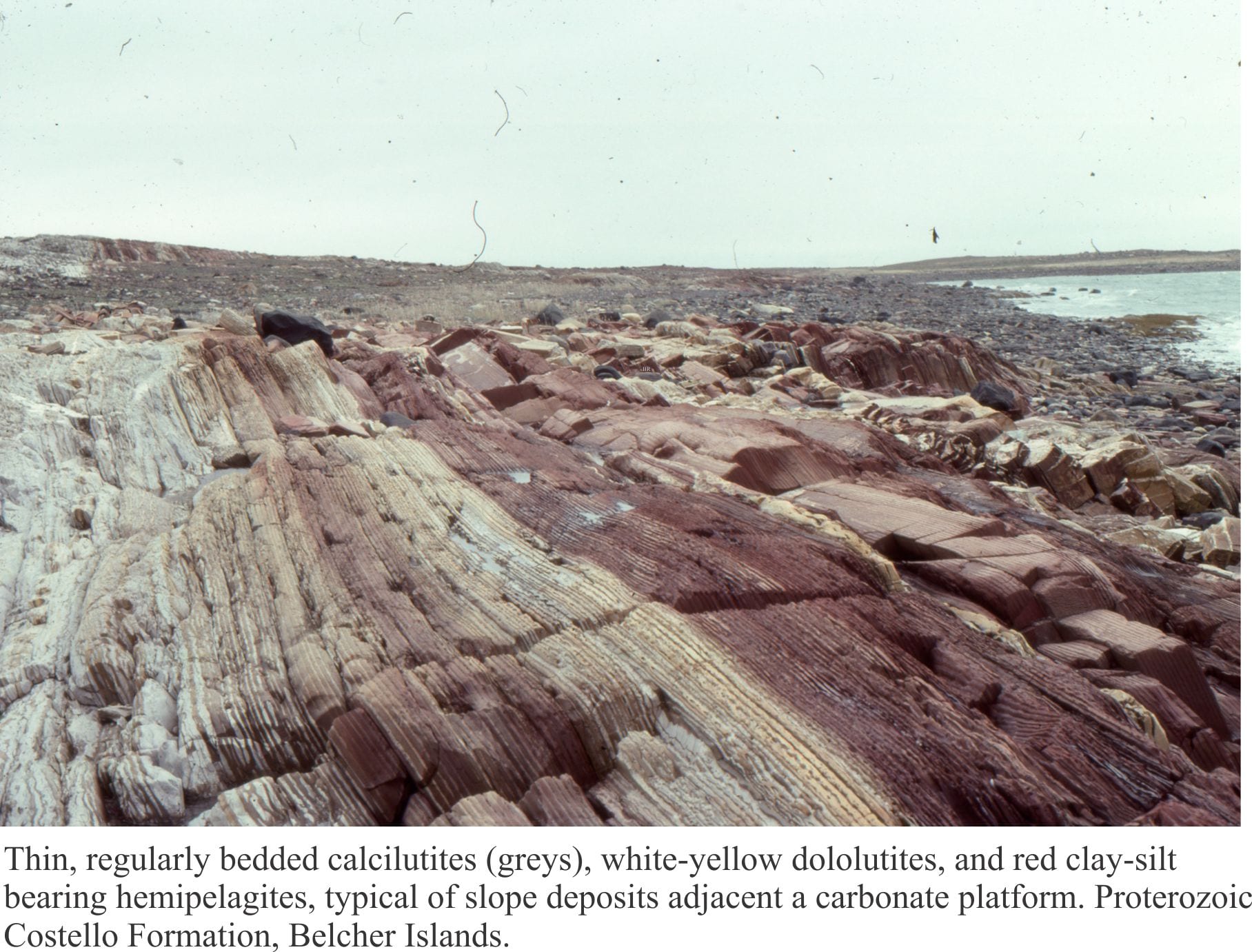

Graded bedding: Also called normal grading. A depositional unit in which there is an upward decrease in grain size (normal grading). This structure is indicative of deposition from turbulent sediment-water mixtures; it is one of the defining characteristics of turbidites. It can also form in still, non-turbulent water from suspension fallout where the largest particles fall fastest – for example seasonal varves, airfall volcaniclastics in water, and hemipelagites.

Groove casts: Straight to slightly arcuate furrows formed when objects are dragged across a soft sediment surface. The grooves are subsequently filled with sediment and exposed as casts at the base of the overlying bed. Groove casts provide ambiguous paleocurrent azimuths (180o apart). They are common at the base of turbidites, and frequently accompany other sole marks like flute casts, roll and skip marks.

Gutter casts: Straight scours several centimetres deep, that in some cases may represent erosion downflow of objects on the depositional surface, and in others the product of helical flow or eddies. Like other sole marks, they present as casts on the base of an overlying bed.

Herringbone crossbedding: Two crossbed sets, one above the other, where the foresets in each dip in opposite directions. The opposing foresets can be interpreted as representing tidal current asymmetry – one set formed during flood tide, the other during ebb tide. This structure is best identified where the 3-dimensional attributes of bedforms can be observed to avoid the ambiguity of apparent foreset dips.

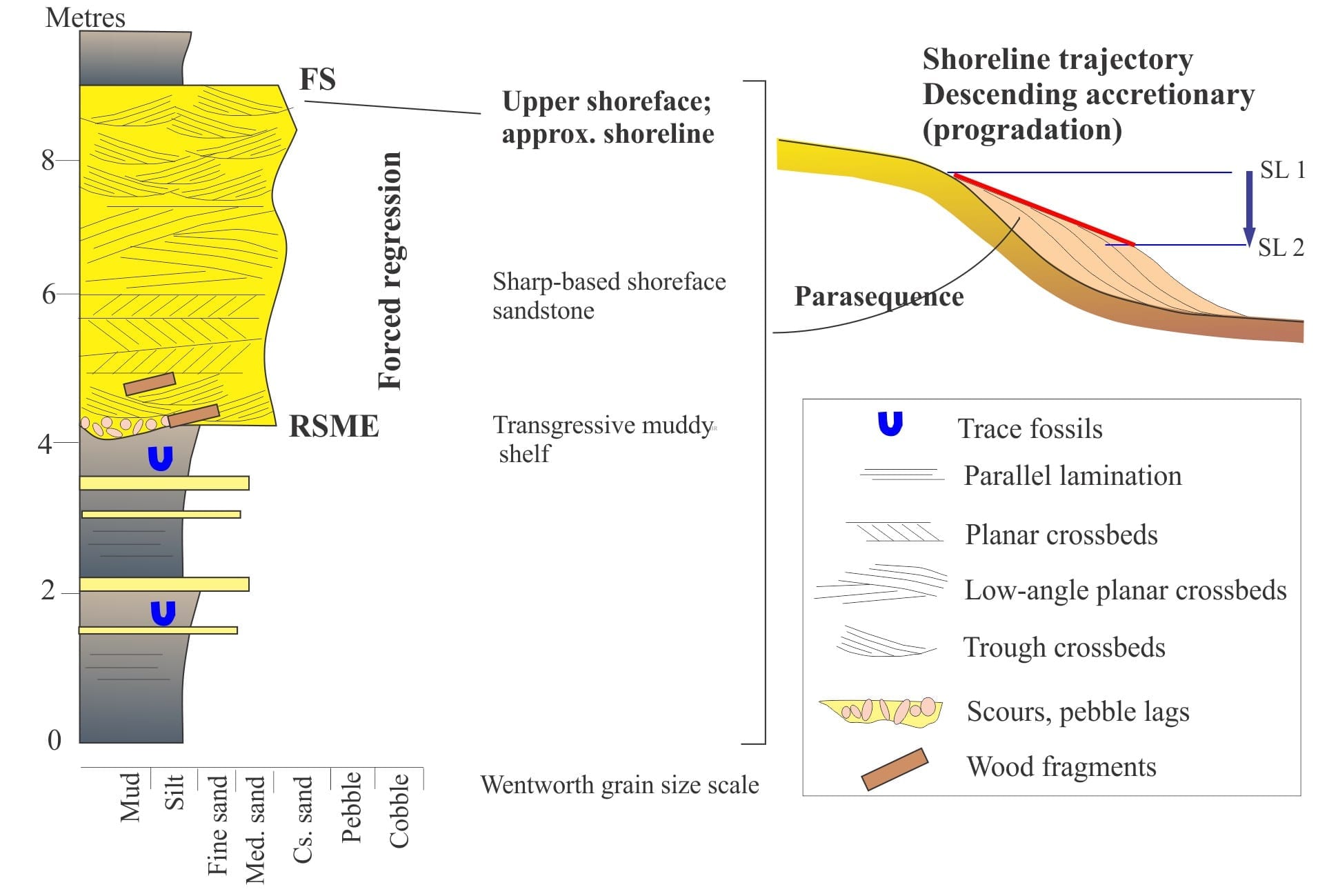

Hummocky cross-stratification: (HCS). Low relief, laminated, mound-like bedforms and intervening troughs or swales. Mound amplitudes are only a few centimetres, and intermound spacings of 2-4 metres. They are mostly fine-grained sandstone, but may contain basal pebble layers. Successive generations of HCS truncate underlying bedforms. HCS forms during storms where unidirectional flowing bottom currents, possibly as sediment gravity flows generated during storm surges, are simultaneously moulded by the oscillatory motion of large storm waves. They are good indicators of storm wave-base. Their preservation potential above storm wave-base (i.e. over the shoreface) is low.

Hydraulic jump: A region of turbulence that develops in channels when Froude supercritical (Upper Flow Regime) conditions slow to subcritical conditions (tranquil, Lower Flow Regime), producing an instantaneous increase in turbulence and flow depth.

Imbrication: The alignment of platy or bladed clasts (usually in pebbles or larger) in relatively strong unidirectional currents. The flat clasts dip upstream, and tend to be stacked one upon the other. Most common in coarse grained fluvial deposits. They are good paleocurrent indicator.

Interference ripples: Across the sediment-water interface, two sets of ripples each set having a different orientation, will cross each other forming an apparent interference pattern. These structures are common on modern intertidal and shallow subtidal flats and platforms. In the rock record, the two sets will exist on the same bedding plane.

Isotropic HCS: Applies to hummocky cross-stratification where the geometry and dip of laminae are the same for profiles viewed at different orientations of the same hummock. Cf. non-isotropic HCS.

Lamination: A style of bedding characterized by sediment layers a few grains thick. Lamination can develop in muddy sediment from subtle variations in the suspension load, for example seasonal sediment load variations in lacustrine settings that produce varves. In sandy sediments they can from processes such as wave swash-backwash across a beach, or supercritical shear across the depositional surface of a sediment gravity flow (e.g., turbidite, sandy debris flow). Lamination can also form from biotic processes as in microbialites and stromatolites.

Lateral accretion surface: Depositional surfaces that dip 15o to 25o that form on the accretionary margins of sinuous fluvial and tidal channels; they accrete foreset-like towards the opposite channel cut bank. They are commonly associated with point bars (an alternative term). Deposition at different stages of stream flow produces a range of sedimentary structures including ripples, 2D and 3D subaqueous dunes, erosional surfaces including chutes, and laminated sand-mud at low flows.

Lateral linkages (stromatolites): Laminae that extend from one stromatolite dome or column to its neighbours and covering the intercolumn sediment.

Lebensspuren: The German word for traces and trace fossils left by animals on or within the sediment.

Lee face (bedforms): The steep, angle of repose face on bedforms, such as ripples and sandwaves, that faces down-flow. Bedload is moved up the stoss face (upstream face) to the bedform crest, and subsequently avalanches down the lee face. Immediately downstream of the lee face is a region of relatively low fluid pressure that is detached from the main flow.

Lenticular crossbedding: Sand ripples that occur as single bedforms within laminated mudstone. They commonly occur with flaser beds. They are commonly found on tidal flats and shallow, low energy subtidal environments such as in lagoons. Together, the bedforms provide evidence for tidal current asymmetry.

Linguoid ripples Asymmetric ripples that have crest lines convex downstream and their lee slope on the convex side. Lee slope deposition fills spoon-shaped scours that migrate in tandem with the ripple. cf. Lunate ripples.

Load casts: Sole marks, or sole structures consisting of bulbous sand or silt structures that protrude into and deform underlying beds – they are most pronounced when protruding into mudrocks. Load casts, or load balls may become disconnected from the parent sand bed. They form during early compaction and are commonly associated with dewatering structures. Soft mud squished between load casts may produce wispy flame structures.

Low angle crossbedding Crossbedding in which foreset laminae and crossbed set boundaries are generally less than 15°. Parting lineations are common on bedding exposures of laminae. They tend to form in upper flow regime conditions. Low angel crossbeds are common in beach sand, and in the proximal parts of fluvial overbank and crevasse splays.

Lunate ripples Asymmetric ripples that have crest lines concave downstream and their lee slope on the concave side. Lee slope deposition fills spoon-shaped scours that migrate in tandem with the ripple. cf. linguoid ripples

Massive bedding: A layer of sediment that appears to be internally structureless. Note however that x-ray radiography of such beds commonly reveals subtle laminations or bioturbation.

Megaripple: Large ripple-like bedforms, generally measuring 10s of centimetres amplitude, with wavelengths to 50 m and more. Although their profile is ripple like, they commonly are not a single bedform, but a complex of amalgamated bedforms. Tabular crossbedding tends to dominate but trough crossbeds also occur. Also called sandwaves.

Micobialite: A recent term for laminated mats composed of microbes including bacteria, cycanobacteria, and red and green algae; it replaces the term cryptalgal laminate that is generally applied to fossil laminates, particularly (but not exclusively) Precambrian. The laminates may be flat and uniform, or tufted, pustulose, and polygonal, resulting from desiccation or, in arid environments, evaporite precipitation.

Molar Tooth structure: Crumpled to sinuous, occasionally cross-cutting, vein-like structures in calcareous to dolomitic mud rocks; in places they superficially resemble deformed burrows. Typically, a few millimetres wide, and extending 20-30 cm from bedding; they are filled with micritic calcite or dolomite. Their name is derived from the bedding plane expression where they appear like elephant molar teeth. Most common in shallow water Precambrian carbonate and siliciclastic rocks. They have been ascribed to desiccation, syneresis, and fossil algae, but the most convincing explanation is that they were seismically induced fractures during shallow burial (B. Pratt, 1998 – PDF, link above).

Mud cracks: See Desiccation cracks.

Parallel bedding: Bedding where top and bottom bedding planes are reasonably parallel for some distance or areal extent. There are no specified limits to this style of bedding; use of this term should be qualified by the limits of the observations, in outcrop or subsurface.

Parting lineation: A crudely linear pattern of rock breakage, usually seen only in bedding plane exposure of laminated sandstones. It is attributed to high flow velocities where the long axes of sand grains become aligned. Measured current directions are ambiguous.

Percussion marks: Abrasions and indentations formed from clast impacts during sediment transport, found on sand-sized through gravel clasts. Scanning electron microscopy is best for observing the marks on sand grain surfaces. They commonly form in highly agitated flows, on beaches, aeolian settings, and fluvial and alluvial channels.

Plane bed: Refers to hydraulic conditions where parallel laminations form; it is an important component of the Flow Regime hydraulic model. There are two plane bed conditions: (1) Where velocity flow in the Lower Flow Regime (LFR) is sufficient to move sand grains, but not sufficient to form ripples. (2) Under Upper Flow Regime (UFR) conditions, where flow washes out LFR dune bedforms to form parallel laminated sand; under these conditions plane bed indicates the transition from LFR to UFR.

Point bar: An accumulation of sand and mud on the inside, or accretionary margin of a channel bend. They are a characteristic bedform in high sinuosity rivers. Internally they are organised into continuous or discontinuous, channel-dipping foresets of sand and mud; sand is more dominant near the channel, mud, silt and carbonaceous material on the upper surface where there is also a transition to the adjacent flood plain. Each foreset contains laminated and crossbedded sandstone. Foresets may also contain discordances from local erosion. A stratigraphic column drawn from the channel, through the point bar to flood plain presents a classic fining upward facies succession.

Rafted clasts: Clasts carried by floating root tangles or less commonly seaweed, and floating ice, that are eventually released and deposited, often far from their original source. Also called drop stones.

Reactivation surface: The lee face of bedforms, such as ripples and larger subaqueous dunes, that is eroded during a reversal of current. When the current returns to its normal flow, the bedform will reactivate and continue to advance downflow. These structures are useful indicators of tidal current asymmetry (ebb-flood reversal). See also interference ripples, lenticular and flaser bedding.

Resting traces: (Trace fossils) (Cubichnia) The impressions of animals taking a break (or perhaps dead). They tend to reflect animal shapes such as starfish, or arthropods like Trilobites. They occur on bedding planes.

Reverse grading: Reverse, or inverse grading is the continuous upward increase in grain-size, and/or the proportion of coarse grains in a flow unit or bed. It is less common than normal grading. It is most easily observed in coarse-grained debris flows and in some pyroclastic density currents.

Rhodolith: Pebbles and shells encrusted with calcareous coralline red algae. They are important contributors to cool-water carbonate sediments and limestones A common example is the alga Lithothamnion.

Rill marks/grooves: Linear, sinuous, and rhomboid-shaped shallow scours that commonly develop on beaches from the swash and backwash of waves. They are usually a few grains thick. They have relatively low preservation potential.

Ripple: Bedforms that develop by movement of sand and coarser-grained sediment at the sediment-water interface under unidirectional and bidirectional flow. In unidirectional flow, ripples generate an asymmetric profile, with an upstream stoss face, and a downstream lee face. Grains move as bedload up the stoss face and tumble, or avalanche down the lee face. The lee face dips in the direction of flow. Symmetrical, bidirectional ripples form beneath waves in response to wave orbitals interacting (to and fro) with the sediment.

Ripple amplitude: The height of a ripple of dune bedform, measured from the trough low point to the crest.

Ripple brink point: The location on a ripple where the stoss face changes abruptly to a lee face.

Ripple crest: The crest is measured from the point of flow reattachment to the point of flow separation; in ancient structures the latter roughly coincides with the brink point at the top of the lee (avalanche) face. Crest and trough are usually considered together.

Ripple index: The ratio of ripple wavelength (measured from brink point to brink point, or trough to trough) to amplitude.

Ripple trough: Measured from the point of flow separation to flow attachment on the downstream bedform.

Ripple wavelength: The distance between successive ripple or dune bedforms (also wave forms), measured from brink point to brink point, or trough to trough.

Rip-up clasts: Clasts of coherent sediment that are formed by erosion of a bed; they are commonly muddy, held together by the cohesiveness of clays. They can range from millimetres to metres in cross-section width. They commonly form in fluvial and alluvial channels, turbidites and debris flows, across storm-dominated shelves, and turbulent pyroclastic density currents.

Sand volcanoes: Small volcano-shaped mounds of sand (and other sediment) that accumulate above dewatering conduits. Dewatering pillars and sheets tend to form in deposits that have permeability barriers, such as mud interbeds, or graded bedding (e.g. turbidites). They can also form during seismic events, particularly in areas where the watertable is very shallow.

Sandwaves: Large dune-like bedforms commonly found on sandy platforms and shelves subjected to strong tidal currents. Amplitudes range from a few decimetres to several metres; wavelengths from metres to 100s of metres. Usually they are not single bedforms, but complex, compound structures that reflect changing tidal current flow and in some cases modification by surface waves.

Sediment gravity flow: Sediment-water mixtures that flow downslope under the influence of gravity. Each flow is a single event. In marine and lacustrine environments such flows include grain flows, turbidity currents and debris flows. They are the main depositional components of submarine fans. Each flow type has a distinctive rheology. Each leaves a characteristic sedimentologic signature depending on the degree of turbulence within the body of the flow, the amount of mud in the sediment mix, and whether the flow is supported by matrix strength, turbulence, or shear. Flows may be initiated by seismic events, gravitational instability of sediment, or storm surges. The terrestrial equivalents include mud flows and lahars.

Sedimentary boudinage: Sedimentary layers that are pulled apart, leaving isolated pods, or boudins, that may also be rotated. There may also be microfactures through the extended layer. It is a type of soft sediment deformation. This phenomenon is most common in cohesive mudrocks that are interbedded with sandy lithologies. The stretching may be initiated by down-slope mass movement or slumping, for example on continental slopes.

Seismite: Deformation of soft or firm sediment during seismic events (commonly earthquakes). Soft sediment deformation occurs during liquefaction, fluidization, and mobilization of single beds or thick sediment packages, producing normal and reverse-thrust folds, faulting, dewatering and flow structures. Spectacular examples crop out along the margins of Dead Sea.

Sole marks: The general name given to structures that form on a depositional surface and are subsequently filled with sediment and exposed as casts at the base of the overlying bed. Common examples include flute, groove, skip, gutter and load casts, and roll marks.

Stationary waves: Also called standing waves. Surface waves formed during the transition from subcritical to supercritical flow. They are the surface manifestation of, and are in-phase with antidune bedforms on the channel floor; the waves migrate upstream in concert with the deposition of backset laminae on the stoss slopes of antidunes. Stationary waves that break (upstream) have become unstable. Unstable wave eventually decay and surge downstream.

Storm berm/ridge Low amplitude mounds, a few centimetres to decimetres high that have gently rounded surfaces on the seaward margin but may be steeper landward. They form when storm waves move gravel from the shallow shoreface to the beach and beyond the high or spring tide limit.

Stoss face: The inclined surface on the upstream side of bedforms such as ripples and dunes. It is rarely preserved because sediment is continually being removed from the stoss and deposited on the lee face in concert with bedform migration.

Straight-crested ripples: Ripples that have non-sinuous crests and form parallel arrays. They are also called 2-dimensional ripples, analogous to 2-dimensional dune bedforms. cf. 3-dimensional ripples.

Stromatolite: Biogenic structures consisting of laminated microbial or cryptalgal mats, that form distinctive mounds or branched structures. Laminae are flat to convex upward. Their relief above the sediment-water interface ranges from a few millimetres to several metres. The morphology of stromatolites is best seen in cross-section profiles. Precambrian examples consisted primarily of cyanobacteria; they are understood to be the first photosynthetic organisms that ultimately gave rise to atmospheric oxygen. See also thrombolite.

Stylolite: Saw-tooth like, discordant seams that result from pressure solution of rock components (framework clasts and cements). They are most common in carbonates but can form in siliciclastic rocks. They represent differential compressive stresses at grain-to-grain contacts, the dissolution and mass transfer of carbonate or silicate by diffusion and fluid flow. Stylolites commonly parallel bedding (from normal compressive stress) but also form oblique to bedding in sequences that are structurally deformed prior to deep burial.

Subaqueous dunes: Any ripple or dune-like bedform that forms in flowing water. An SEPM workshop in 1987 attempted to revise crossbed terminology, by incorporating the 3-dimensional aspects of bedforms larger than common ripples, with their inherent hydraulic properties. They recommended that the term dune be used, with the basic distinction between subaerial and subaqueous dunes, of all sizes. Subaqueous dunes were separated into:

- 2 dimensional subaqueous dunes having relatively straight crest lines and planar foreset contacts; they correspond to tabular crossbeds, and

- 3 dimensional subaqueous dunes having sinuous crest lines and spoon- or scour-shaped foreset contacts. These correspond to the classic trough crossbeds.

Supercritical liquid: A liquid that has properties somewhere between a gas and a liquid. For example, for CO2 these properties include high solubility in oil and water; density similar to the liquid phase but much lower viscosity – the latter property enhances flow through pipes (transport)and through porous rock; low surface tension.

Swaley cross bedding Formed in conjunction with hummocky cross stratification. They occur as low relief depressions, where infilling laminae are continuous from crest to crest, and dip less than 15°. They also occur in beds lacking HCS and may represent preservation above fairweather wavebase (HCS are usually found below fairweather wavebase). A possible reason for this is that the swales are negative features on the sea floor that can avoid truncation and reworking by fairweather waves. HCS on the other hand are more likely to be reworked by fairweather wave orbitals.

Synaeresis cracks: Cracks in sediment formed by compaction, changes in salinity, and in some cases by dewatering of sediment during seismic events. They are not formed by subaerial exposure and desiccation. Their shape and geometry is superficially like that of mud cracks; V-shaped in cross-section, straight to slightly curved strands in plan view, and occasionally polygonal.

Synoptic relief: The relief above the sediment surface of an actively growing cryptalgal or microbialite mat. In stromatolites, each lamination represents a period of growth at the sediment surface – the maximum amplitude of these concave upward mats is the synoptic relief, or growth relief. Synoptic relief is commonly no more than a few millimetres but can be as high as 4-6 m in large, platform margin stromatolite reefs or buildups.

Tabular crossbed: Crossbeds having a planar bottom set (boundary) across which foresets are in tangential or abrupt angular contact. Also called 2D subaqueous dunes.

Tempestite: The deposit and/or erosional surface developed during a storm. Onshore and offshore erosional surfaces usually form as the storm waxes; tempestites usually accumulate during the waning stage of a storm. Typical sedimentary structures include HCS, SWS, modified wave ripples, combined flow climbing ripples, upper plane-bed laminae, and graded beds including turbidites.

Thrombolite: Cryptalgal or microbialite structures that have clotted textures rather than the more structured, laminated and branched stromatolites.

Tidal bundles Crossbedding in which there is repetition of sandstone foresets, each coupled to a veneer of siltstone or mudstone in decimetre to metre sized tabular crossbeds. The fine-grained laminae may be continuous or discontinuous across the foresets. The muddy layers may also be carbonaceous or micaceous. The regular grain size repetitions are commonly inferred to be the product of tidal current reversals where tidal flow in one direction (flood or ebb) is stronger than the opposite flow. They are commonly associated with shelf sandwaves and sand bars.

Traction carpet: Above the flow threshold velocity, non-cohesive grains at the sediment-water interface move by rolling, jostling, and sliding. Grain movement is contained within the bedload. See also saltation load, suspension load.

Trough crossbed: Defined by its concave, spoon-shaped basal contact that truncates previously formed crossbeds. Foresets have a similar geometry and generally are tangential with the base. Also called 3D subaqueous dunes. They are common under conditions of confined, channelised flow.