Please note – I no longer maintain Glossaries by alphabet; A, B, C… etc. All items on these pages have been moved to subject-specific glossaries such as Volcanology, Sedimentary facies and processes, and so on. The list of subject-based glossaries can be viewed in the drop-down menu on the navigation bar. These glossaries are continually updated.

Please note – I no longer maintain Glossaries by alphabet; A, B, C… etc. All items on these pages have been moved to subject-specific glossaries such as Volcanology, Sedimentary facies and processes, and so on. The list of subject-based glossaries can be viewed in the drop-down menu on the navigation bar. These glossaries are continually updated.

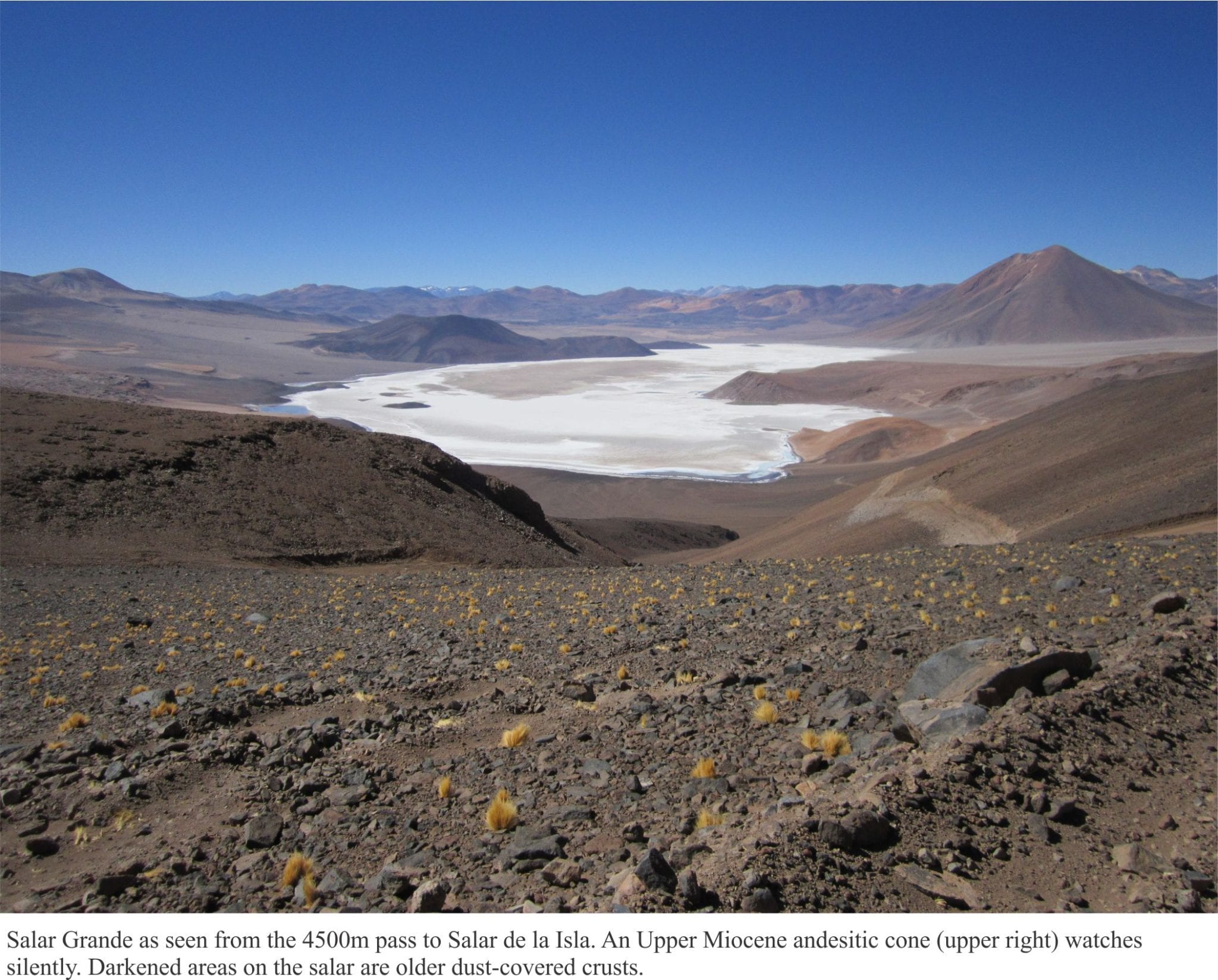

Sabkha: Broad, flat areas of evaporitic sand-mud flats that form in arid to semi-arid climates. Modern coastal sabkhas are part of the intertidal realm, occupying the supratidal zone that is infrequently flooded by seawater by very high tides and storm surges. Sabkhas can also occur in interdune areas where the local watertable is close or at the surface. Common mineralogy includes gypsum, anhydrite and halite. Precipitation of evaporites takes place at the surface and within the shallow sediment column. Sabkhas also have specialised invertebrate faunas, and microbial communities that form extensive, desiccated mats.

Salina: A salt-water pond, spring or lake, either natural or artificial. From the Spanish for salt pit, and earlier Latin salinus meaning saline. Cf. Playa Lake.

Saline intrusion: See seawater intrusion.

Saline lake: A terrestrial water body where evaporation exceeds surface freshwater influx and fresh groundwater seepage. Recharge may be seasonal and intermittent. Intense evaporation results in precipitation of salts, commonly halite and gypsum. Lakes may be connected to inflowing and outflowing drainage, or they may be endorheic. See also Playa Lake

Saline lake brines: Unlike seawater, terrestrial brines have widely variable compositions, depending on local soil and bedrock compositions, groundwater chemistry, and the degree of evaporitic drawdown. Typical brines contain Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl–, SO42-, HCO3–, CO32-, and SiO2, but concentrations are highly variable. pH ranges from highly alkaline to highly acidic. Evaporation pathways produce a succession of different minerals. See also calcite-gypsum divides.

Salt marsh: A marsh dominated by salt-tolerant herbaceous plants and microbial mats in upper intertidal to supratidal areas, usually flooded during spring tides and storm surges. They are important habitats for invertebrates and vertebrates. Drainage is principally by shallow tidal channels. Sediment is commonly a mix of fine sand and mud. A degree of sediment desiccation may occur during prolonged dry periods. See also sabkha, tidal flats.

Saltation load: Grains that temporarily leave the sediment-water-air interface, for example by bouncing along the surface under high flow velocities, but where fluid forces are not sufficient to maintain suspension. The saltation load is part of the bedload. See also Traction carpet.

Sand: According to the Wentworth scale, it includes all grains from 0.0625 mm to 2 mm (4 to -2 phi).

Sandspit: An emergent sand bar at the entrance to a bay or estuary. At one end the spit is attached to headlands; at the other an open tidal channel that allows seawater exchange between the bay and open sea. Larger spits may also have a veneer of sand dunes. Cf. Barrier island; Tombolo.

Sand volcanoes: Small volcano-shaped mounds of sand (and other sediment) that accumulate above dewatering conduits. Dewatering pillars and sheets tend to form in deposits that have permeability barriers, such as mud interbeds, or graded bedding (e.g. turbidites). They can also form during seismic events, particularly in areas where the watertable is very shallow.

Sandwaves: Large dune-like bedforms commonly found on sandy platforms and shelves subjected to strong tidal currents. Amplitudes range from a few decimetres to several metres; wavelengths from metres to 100s of metres. Usually they are not single bedforms, but complex, compound structures that reflect changing tidal current flow and in some cases modification by surface waves.

Satellite altimetry: Measurement of sea level from a satellite-borne microwave transmitter. The actual sea level is calculated by subtracting the the altimeter heights (from a specified area of the sea surface) from the satellite orbit height. The reference surface is the geoid, for which there is precise data.

Saturated zone (hydrogeology): The part of an aquifer where pore spaces are permanently filled with water. In unconfined aquifers this occurs below the watertable. Confined aquifers are always completely saturated. Also called the phreatic zone.

Saturation: Saturation (Ω) is the ratio of the measured ion activity (or concentration) product and the standard solubility product (Ksp) for a mineral. If Ω >1 then the solution is supersaturated with respect to the mineral; if Ω <1 then it is undersaturated and the mineral will dissolve. If Ω = 1 then the mineral is at equilibrium with the solution.

Saturation depth: In ocean chemistry this boundary identifies when seawater becomes unsaturated with respect to calcite (or aragonite). The saturation depth is determined by comparing the measured solubility product of either the activity or concentrations of Ca2+ and CO32- in seawater samples, with the equilibrium solubility product at the same temperature and water pressure.

Schwabe cycles: The 11 year cycle of sunspot waxing and waning discovered by Heinrich Schwabe in 1843. See sunspot cycles.

Scoria: Mostly lapilli-sized fragments of vesicular, porous pyroclasts, generally of basaltic or andesitic composition – hence dark brown-red colours. Some scoria fragments may be strung out into lacy threads. Cf. Pumice.

Sea grass: (eel grass) Beds of sea grass (e.g. the genus Zostera) are found covering sandy tidal flats, extending into the shallow subtidal zone. Slender leaves can grow to 100 cm long. They tend to grow in areas where there is little substrate erosion, but in currents strong enough to remove mud and silt. They are a monocotyledon, a flowering plant that produces rhizomes. They provide important habitats and food sources; they also dampen sediment dispersal.

Sea level: Eustatic sea levels are measured with reference to a fixed datum like the centre of the Earth. For any datum that is not fixed, like a shoreline, sea level must be considered relative. Relative sea levels are affected by changes in glacio-eustasy, steric, and tectonic processes. Sea level is not the same everywhere because of differences in the gravitational potential. This is the main reason for the system of locks in Panama and Suez canals. Sea level equates with baselevel for depositional systems.

Seamount: A basaltic volcanic edifice on an oceanic plate, that rises 1000s of metres above the sea floor, derived from mantle plume hotspots. The largest seamount on earth, Mauna Kea (Hawaii) rises 4205m above sea level but extends about 10,200m from the sea floor. Seamounts that broach the surface may provide habitats for coral reefs. Once volcanic activity ceases, the edifice will gradually sink under its own weight (an isostatic response).

Seawater-fresh water interface: The boundary between fresh water and seawater in coastal aquifers, and aquifers that extend beneath a marine shelf. The boundary is diffuse. In coastal aquifers the depth to the interface depends on the watertable elevation above sea level – the depth is governed by the Ghyben-Herzberg principle.

Seawater intrusion: (saline intrusion) The replacement of fresh groundwater by an intruding wedge or lens of seawater. This commonly occurs in coastal aquifers where excessive fresh groundwater withdrawal results in a fall in the local watertable, and a corresponding rise in the fresh water/seawater interface by 40 times the amount the watertable has fallen. Sea water intrusion is, for practical purposes, irreversible. See Ghyben-Herzberg principle.

Secondary porosity: Porosity that is created during burial diagenesis by the dissolution of chemically reactive grains such as carbonates and feldspars. Secondary porosity can enhance the overall porosity of a rock, particularly if primary intergranular pore volumes have been occluded by cements. Secondary pores may be larger than those formed during deposition, where entire grains are dissolved. Partial dissolution along twin or cleavage planes in minerals like feldspar, will result in irregular grain boundaries.

Sector collapse: The collapse of a large portion of a volcanic edifice, usually on steep flanks can occur during an eruption, or long after. Collapse during an eruption may trigger lateral blasts that produce pyroclastic flows (as occurred on Mt St. Helens in 1980). The sector usually breaks up into blocks that produce avalanches and lahars, rather than failing as a coherent unit. Flank collapse into the sea can result in tsunamis.

Sediment gravity flow: Sediment-water mixtures that flow downslope under the influence of gravity. Each flow is a single event. In marine and lacustrine environments such flows include grain flows, turbidity currents and debris flows. They are the main depositional components of submarine fans. Each flow type has a distinctive rheology. Each leaves a characteristic sedimentologic signature depending on the degree of turbulence within the body of the flow, the amount of mud in the sediment mix, and whether the flow is supported by matrix strength, turbulence, or shear. Flows may be initiated by seismic events, gravitational instability of sediment, or storm surges. The terrestrial equivalents include mud flows and lahars.

Sediment routing system: The path that sedimentary particles follow from their source to final destination in a depositional sink. That path, or route, may be relatively direct, or circuitous with stopovers at sites of temporary storage (for example, a fluvial point bar). The character of the system depends feedbacks among landscapes, tectonics (denudation, erosion), climate, travel time, and depositional processes.

Sediment transfer zone: The zone of sediment dispersal between its source area (dominated by erosional processes), and depositional sink. In this zone there is generally a balance between sediment transport and deposition. Sediment dispersal in the transfer zone takes place via many different terrestrial and marine processes.

Sedimentary basin: From a geodynamic perspective, a region of prolonged subsidence, dependent on the rheology and thermal structure of the crust and lithosphere mantle. The four most common mechanisms promoting subsidence are: lithospheric stretching, cooling and densification, flexure from loading the crust with sediment and volcanic edifices, and flexure from tectonic loads.

Sedimentary boudinage: Sedimentary layers that are pulled apart, leaving isolated pods, or boudins, that may also be rotated. There may also be microfactures through the extended layer. It is a type of soft sediment deformation. This phenomenon is most common in cohesive mudrocks that are interbedded with sandy lithologies. The stretching may be initiated by down-slope mass movement or slumping, for example on continental slopes.

Semidiurnal tides: Two tides every 24 hours. Diurnal tides (one every 24 hours) occur in areas where coastline shape and bathymetry interfere with the normal semidiurnal cycle.

Sequence stratigraphy: A method of stratigraphic analysis that recognises that the sedimentary record is organized into discrete, but genetically related stratal packages bound by key stratigraphic surfaces, surfaces that repeat through time and are dynamically controlled by changes in baselevel, accommodation, and sediment supply.

Sequestration: Storage of solid, liquid or gas so that it cannot disperse, or escape. Of recent concern is sequestration of carbon in various forms, particularly CO2 and methane. Natural sequestration occurs on rocks (coal, limestones), soils, and permafrost. Artificial sequestration of supercooled CO2 in certain rock formations (such as depleted oil fields) is considered as one means of controlling CO2 emissions.

Shallow water waves: Waves whose orbitals interact with the sea or lake floor at the point where water depth is about half the wavelength. Open ocean deep water waves eventually become shallow water waves as they approach the shoreline. Here, some of their energy is transferred to the sea floor, and to conserve momentum the waves slow down but increase in amplitude. Tsunamis are considered to be shallow water waves because their wavelengths are measured in 10s to 100s of kilometres.

Shatter cones: Overlapping cone-shaped fracture patterns, pointy end up, observed in rocks subjected to extreme stresses generated by meteorite impacts. May be associated with shock lamellae crystals, such as quartz.

Sheetfloods: Intermittent sheet-like flow during flood events, that is not confined to a channel by spreads laterally. They develop mostly on alluvial fans. Depending on their competence, they carry mud, sand, and gravel. Deposits may show crude grain size grading and ripples. Flow in some sheetfloods is hyperconcentrated.

Shelf break: (or shelf edge) A relatively narrow submarine zone marking the transition from a continental shelf to steeper inclined continental slope – slopes commonly 2o – 5o . The break may interupted by gullies eroded by rivers during sea level lowstands, or formed by submarine slope failures.

Shock lamellae: Parallel laminae in crystals like quartz, that form during extremely high pressures and strain rates during meteorite impacts. They appear as parallel zones that represent deformation or breakage crystal defects. Shocked crystals can be distributed widely during an impact. Cf. Tektites, shatter cones.

Shoreface: The shallow marine environment extending from the low tide zone to fairweather wave base. The sea floor in this region is constantly impinged by wave orbitals. Bedforms of various sizes will form, depending on wave energy and tidal currents.

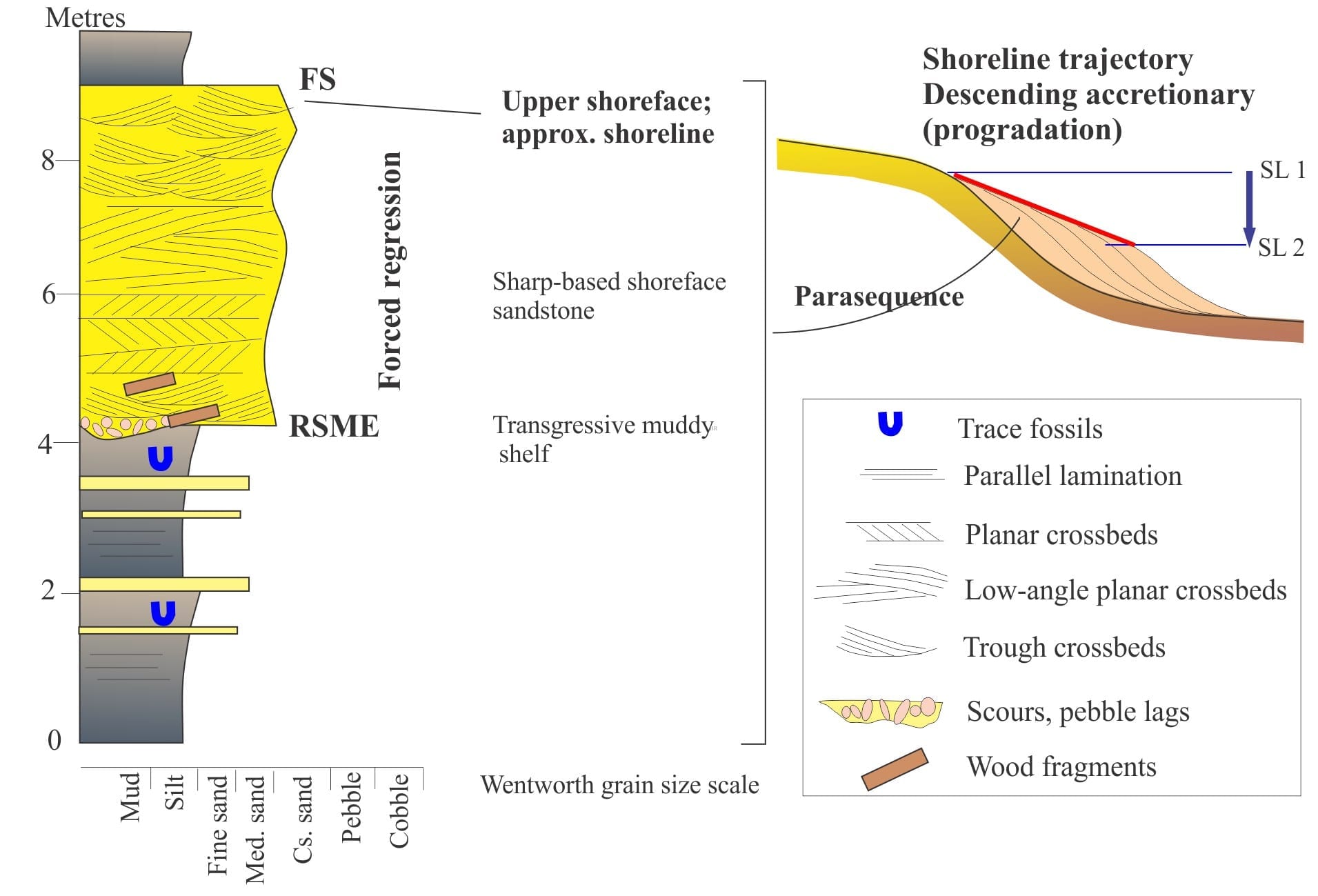

Shoreline trajectory: A 2-dimensional plot of shoreline excursions, either landward or seaward, based on interpretation of sedimentary facies and stratigraphy, using the stacking patterns of successions or parasequences that contain evidence for proximity to paleoshorelines. For example, a progradational trajectory is horizontal; a forced regression trajectory downsteps seaward.

Sieve analysis: A method for measuring grain size distribution in unconsolidated granular sediment, that uses a series of stacked sieves, each sieve containing a standard mesh aperture, coarsest at the top of the stack. Each sieve will retain sediment that is coarser than the mesh size; grains with a minimum diameter less than that mesh diameter will pass through to the next sieve below.

Sieve diameter: The minimum diameter of a particle-grain that will pass through a particular sieve aperture. Spherical grains have equal diameters at all orientations.More elongate or platy grains have maximum and minimum diameters. Sieve aperture sizes are standardised, commonly over a range from -6Φ (pebbles – 4-64 mm) to 4Φ (very fine sand – 0.0625 mm).

Siliciclastic: Sediments composed predominantly of detrital, silica-based minerals; the most common components are quartz, feldspar, and lithic fragments. Heavy minerals such as magnetite, zircon, and tourmaline are important constituents, usually in trace amounts. This broad category includes all grain sizes. It does not include clastic carbonates.

Sills (igneous): Sheet-like feeders of magma to volcanic eruptions that parallel sedimentary or metamorphic layering. In sedimentary successions, they can be mistaken for lava flows (and vice versa). A simple criterion to make the distinction is the thermal alteration of sediment at the upper and lower surfaces in sills.

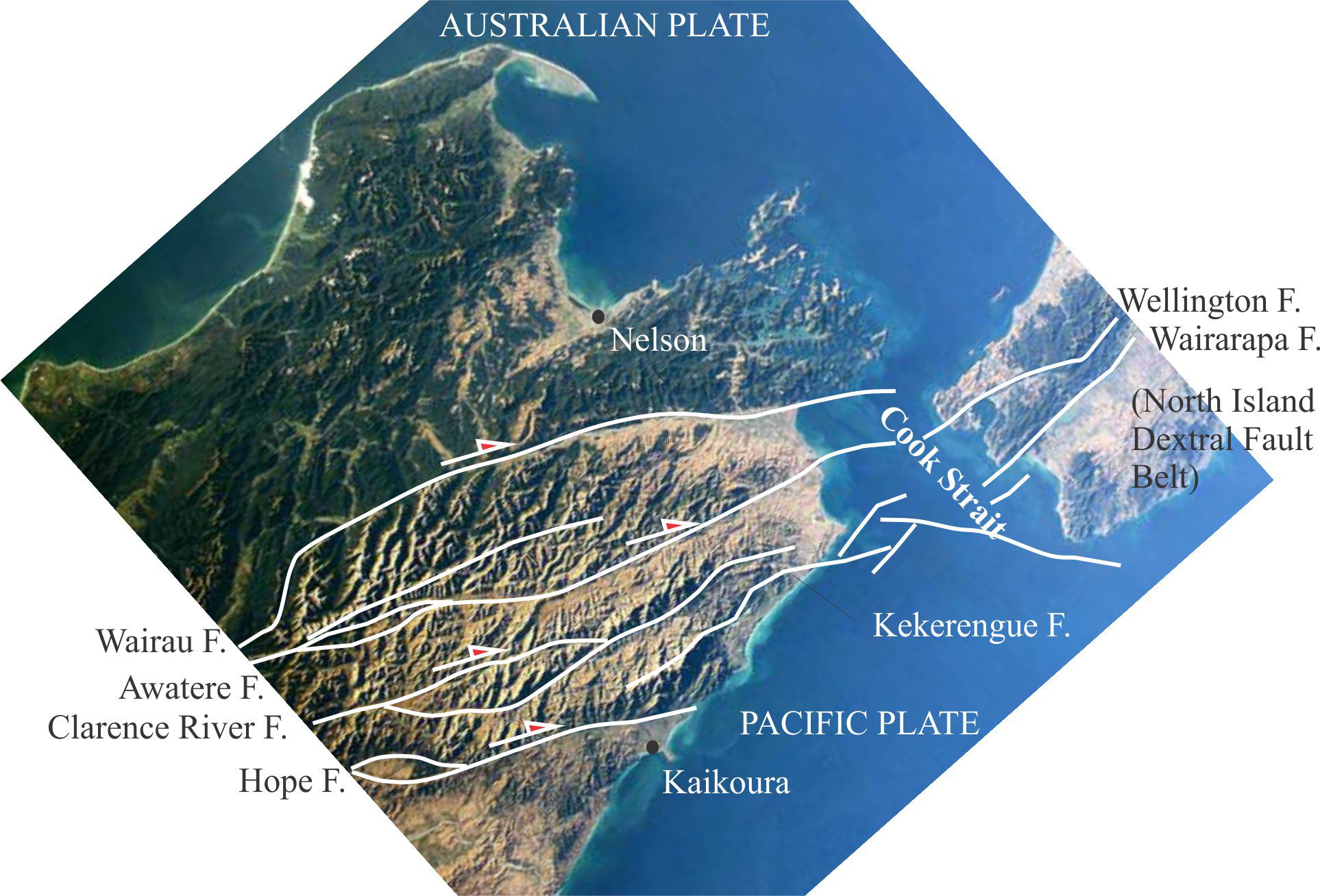

Sinistral: Describes the sense of movement on strike-slip faults. For an observer, the far side of the fault (the fault block opposite) will appear to move to the left. Synonymous with left-lateral displacement or motion.

Sinkhole: Also called Dolines, are collapse structures formed by removal of subsurface rock, either by erosion of dissolution within the vadose and saturated (phreatic) zones, are typical of limestone terrains; they can also occur in landscapes underlain by evaporites. They tend to be circular in cross-section. Collapse usually occurs rapidly into large, subsurface caverns. They are common in karst landscapes.

Sinuosity (fluvial geomorphology): The ratio of river length (along its axis, or thalweg) between two locations, divided by the straight-line distance between the same locations. Meandering rivers have high sinuosity – >1.5 (all those loops); braided rivers (with multiple channels) have low sinuosity (<1.1). Straight channels have a sinuosity of one.

Skewness (grain size): Skewness describes the asymmetry of a frequency distribution. It is a dimensionless number. For grain size statistics, the Folk and Ward Phi-based formula is most commonly used:

Sk = [(ϕ16 + ϕ84 – 2 ϕ50) /2(ϕ84 – ϕ16)] + [(ϕ5 + ϕ95 – 2 ϕ50) / 2(ϕ95 – ϕ5)]

Slickenlines: Fine, usually linear striae on slickensided surfaces that develop during fault block movement. They are good kinematic indicators for determining the direction of slip, or displacement.

Slickensides: The polished or smooth surface on fault planes, that are generally considered the result of grinding during movement of fault blocks. However, shiny surfaces may also be a product of mineral precipitation during deformation. Slickenside surfaces commonly contain slickenlines.

Slow slip events: Small displacements along a subduction zone and its associated faults as a result of continued build-up of strain. The events occur in conjunction with episodic tremor – swarms of very low magnitude earthquakes, barely felt, if at all. None of the displacements results in major earthquakes.

Solar insolation: The flux of solar radiation that Earth (or any planetary body) receives over a given area. It depends on solar output, the incident angle at Earth’s surface (least at the poles), and the variable distance of Earth’s orbit. It also varies according to the three Milankovitch cycles. It is the heat that warms the atmosphere, oceans, and surface of Earth.

Sole marks: The general name given to structures that form on a depositional surface and are subsequently filled with sediment and exposed as casts at the base of the overlying bed. Common examples include flute, groove, skip, gutter and load casts, and roll marks.

Solid solution series: Minerals that share the same basic chemical formula but have different proportions of key elements in their crystal lattice such that crystal form may vary. In sedimentary rocks the most important examples are the alkali (K-Na end-members) and plagioclase (Na-Ca end-members) feldspar groups. Olivine also forms a series with fayalite and forsterite end-members. A mineral’s position in a series reflects the composition and temperature of, for example, the original igneous melts (in the case of feldspar and olivine.

Solidus: At temperatures below the solidus, a material remains solid. In geodynamics it represents the temperature above which partial melting will occur; the solidus isotherm at 1100-1300oC is used to define the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. The variability within this temperature range reflects the degree of hydration in the mantle lithosphere; hydration generally lowers the melting point. Note that the solidus occurs at lower temperatures than the liquidus; i.e. the two do not coincide.

Solifluction: In cold climates, the downslope movement or creep of soils and colluvium during spring thaw. This process is accentuated in permafrost regions where the top of the frozen zone acts as a barrier to moisture infiltration.

Solubility product: Solubility product expresses whether a mineral will dissolve or precipitate in aqueous solutions, at specified temperatures and pressures. For example, aragonite in seawater, the reaction is CaCO3(solid) ↔ Ca2+(aq) + CO32-(aq). At equilibrium the solubility product is

Ksp = (aCa2+).(a CO32-) / (a CaCO3 solid)

The activity of the solid calcite is 1, such that the constant at equilibrium becomes:

Ksp = (aCa2+).(a CO32-)

(aCa2+).(a CO32-) is also called the activity product. In real solutions, if (aCa2+).(a CO32-) is >Ksp, then aragonite will precipitate; if <Ksp it will dissolve. See also saturation.

Solute: A chemical compound that has dissolved in a solvent. In geofluids, the solvent is primarily water; common solutes are various chlorides, sulphates, hydroxides, nitrates and phosphates. In all these compounds, the solute will consist of cations and an anions surrounded by water molecules.

Solute transport: The movement or flow of dissolved mass in a fluid, usually water. The primary mechanisms of transport are advective flow and diffusion. Transport is usually accompanied by chemical reactions.

Solvent: A liquid (usually) capable of dissolving and maintaining solutions of solid compounds. Water is the most prominent geofluid solvent. Organic solvents are important for industrial processes.

Sorting (grain size): Sorting is a measure of standard deviation – the spread of measurements about the mean of a population. The importance of sorting lies in its relationship to the hydraulics of deposition, particularly in relation to reworking and winnowing of certain size classes. For example, in a high energy shallow marine environment, silt and clay sized material will be removed, leaving grains having a relatively narrow size range. The Folk and Ward formula commonly used is:

σϕ = (ϕ84 – ϕ16 /4) + (ϕ95 – ϕ5 / 6.6)

Source to sink: An expression that describes, in very general terms, the journey sediment takes from its source area to its final destination. It encompasses:

- Source area topography, tectonic setting, paleoclimate;

- The changes in sediment composition by physical (abrasion, winnowing) and chemical processes;

- Changes in depositional environments en route,

- The stratigraphic position of sediment at its destination; and

- Post-depositional changes (diagenesis).

Sphericity: In describing the shape of sedimentary grains, reference is made to a standard sphere. Sphericity can be purely descriptive or quantified by measuring the lengths of the three axes and comparing them to an ideal sphere. The term spheroid is synonymous with ellipsoid.

Spherulites: Spherical structures that grow from rapidly quenched fluids. In volcanology, they are commonly found in glassy rhyolites and dacites where they have crystallized directly from the original melt. Usually <10 mm diameter, and tend to occur in clusters or flow bended layers. Each spherulite contains quartz and plagioclase crystallites organized radially.

Spreading ridge: Also called a mid-ocean ridge. New oceanic crust and mantle lithosphere are created at spreading ridges. The oceanic lithosphere is stretched to a few km thin along the ridge axis; in its place, convecting asthenosphere plumes provide the magmas that erupt along the ridge. Spreading ridges are major plate tectonic boundaries.

Spring tides: The highest tides during a full tidal cycle, occurring when the Sun and Moon are aligned (the Moon can be in full or new phase).

Stacking patterns (stratigraphy): The stratigraphic trend of repeated depositional cycles (at any scale). In sequence stratigraphy the stacking of parasequences is the basis for identifying systems tracts. For example, successive parasequences that indicate progressive deepening in a succession would be included in a retrogradational systems tract that develops during transgression. The stacking pattern is also reflected in the shoreline trajectory.

Stalactite: Tubes, straws. and threads of calcite that hang from the ceiling in the drip zone of caves. Groundwater, initially undersaturated with respect to calcite can, with sufficient transfer of atmospheric CO2, become supersaturated, promoting precipitation. Pillars or columns form when stalactites meet stalagmites, their cave-floor counterpart. They are a type of speleothem, a group of cave precipitation structures that includes cave wall linings (drapery), flowstone, and cave pearls. Stalactites and stalagmites can also form from dripping lava.

Stalagmite: Commonly conical shaped mounds of calcite that grow from cave floors as a result of the steady drip of seepage groundwater. They are the cousin of stalactites.

Standing waves: Surface waves formed during high velocity channel flow (upper flow regime), that appear to stand still or migrate upstream. They are the surface manifestation of, and are in-phase with antidune bedforms on the channel floor. In some river channels, standing waves will form over large boulders.

Stepovers: A stepover occurs where the strain at the end of one fault is transferred to the beginning of a parallel fault having the same sense of displacement. Stepovers can be restraining or releasing. They are also described as left or right in the same way that bends are described; at the end of one fault, you look right or left to find its parallel accomplice. Pull-apart basins and pop-up ridges can also form at stepovers depending on whether they are restraining or releasing.

Steric effect (oceanography): The density of seawater changes according to temperature such that it expands as temperatures rise. Changes in sea level can be attributed in part to ocean temperature changes. This is the steric contribution to sea level rise or fall, the other contribution being glacial addition or subtraction of water mass.

Stereonet: A circular grid with two sets of lines: Small circles, analogous to latitudes or parallels, and Great circles analogous to longitudes or meridians. The gird is used to graphically project a sphere onto a plane. The most common type is a Wulff net where small and great circles intersect at right angles. Stereographic projection is an important component of any geologist’s toolbox. It is used to analyse the angular relationships of planes and plane intersections (bedding, crossbedding, fault, fold axial), and linear structures that lie in those planes.

Storm wave base: The maximum depth at which storm-generated waves impinge the sea floor and are capable of moving sediment. Storm wave base is deeper than fairweather wave base.

Stoss face: The inclined surface on the upstream side of bedforms such as ripples and dunes. It is rarely preserved because sediment is continually being removed from the stoss and deposited on the lee face in concert with bedform migration.

Strain (rheology): The deformation of a sediment, rock, or fluid body, that in rigid bodies is measured as changes in location (translation) or rotation, and in non-rigid bodies changes in size (dilation-contraction) and shape (distortion).

Strain rate: The rate at which deformation takes place. At high strain rates many materials will behave in a brittle manner (e.g. earthquakes). At low strain rates and high confining pressures the same materials will behave as plastics and deform by ductile flow. In fluids, shear stress is proportional to strain rate; the proportionality constant is the viscosity of that fluid (viscosity is a measure of resistance to shear deformation.

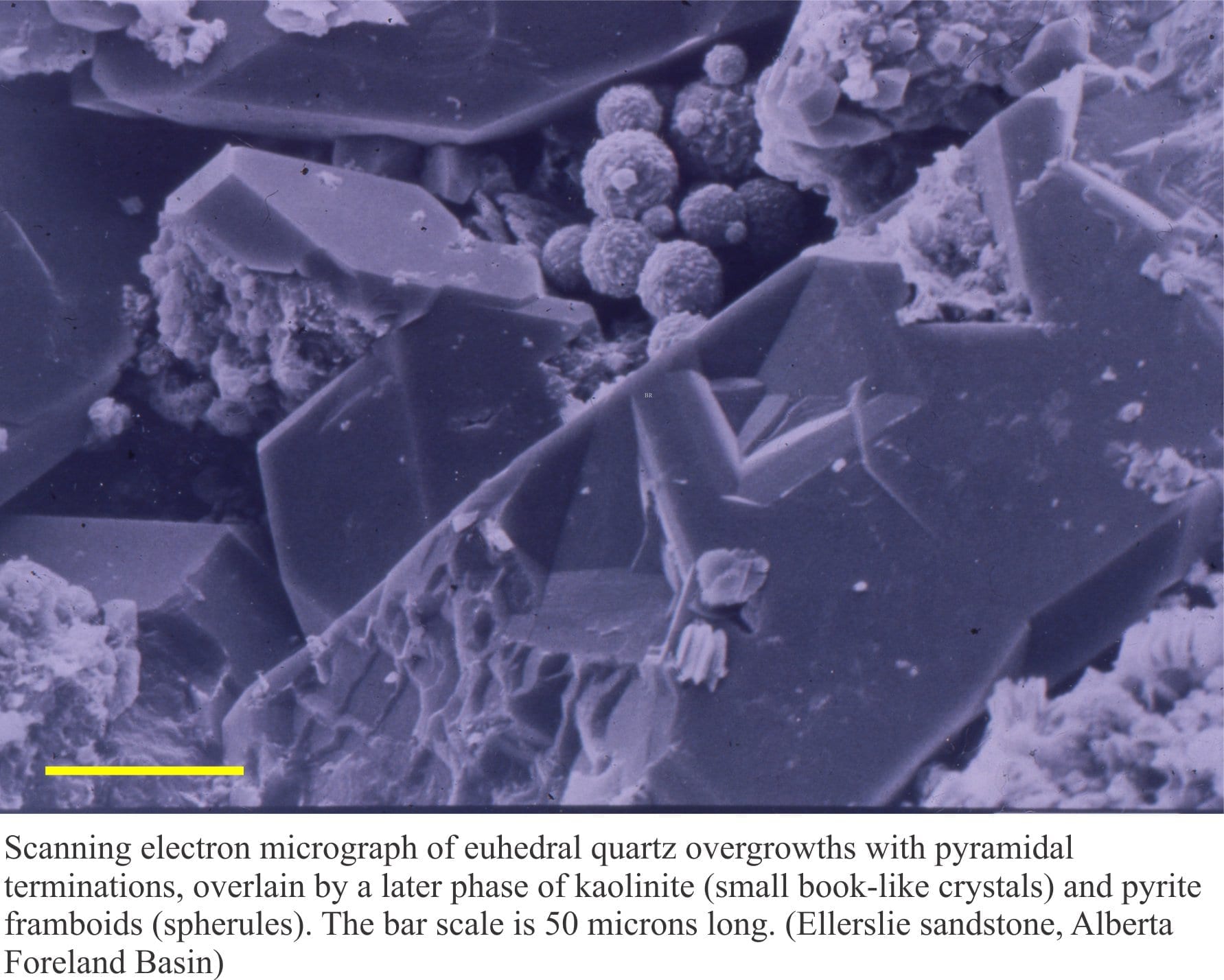

Strained quartz: Used in petrographic descriptions for quartz grains that under crossed polars exhibits sweeping extinction. It results from crystal lattice dislocations during deformation.

Stratigraphic cycles: The periodic repetition of sedimentary facies, fauna and flora associations, sediment chemistry, and hiatuses or discordant surfaces, that represent changing depositional environments, fluctuations in relative sea level and sediment accommodation, migrating shorelines, and the changing conditions of sediment storage and release. Cycles range in thickness from mm to 100s of metres, and duration from minutes to millions of years. They develop from both allogenic and autogenic processes.

Stratigraphic shingling: A term introduced by John Crowell (1974) applicable to strike-slip basins. It involves strike-slip fault controlled migration of a basin depocenter that produces a succession of dipping stratigraphic packages that onlap the basin floor. The packages are stacked like roofing shingles. At any one location the thickness of overlapping shingles might be measured in 100s of m; the cumulative thickness over the life of a strike-slip basin may be >10 km.

Stratigraphic trends: A stratigraphic trend is the relatively ordered, vertical and lateral changes in bed geometry, sediment composition, sedimentary structures, and fossil – trace fossil content. Stratigraphic trends are found at all geological scales, from a few centimetres to 1000s of metres. Typically, we observe them as fining- and coarsening-upward trends. They are a fundamental element of stratigraphy, particularly sequence stratigraphy because identification of parasequences relies on recognition of such trends. Repeated trends comprise stratigraphic stacking patterns. See also shoreline trajectory.

Stratigraphic units: The International Commission on Stratigraphy defines three principle units:

- Time units (Era, Period) that refer only to geological time and not process.

- Time-rock units; strata deposited during a specific interval of time (System, Epoch).

- Rock Units that refer only to the composition and mapability of strata (Formations, Groups).

Stratosphere: The stratified atmospheric layer above the troposphere, that extends 30-50 km altitude. It contains most of the ozone. Temperatures in the stratosphere are maintained by ultraviolet radiation absorption in molecules like ozone (O3). Ultraplinian eruption columns may rise to stratospheric levels.

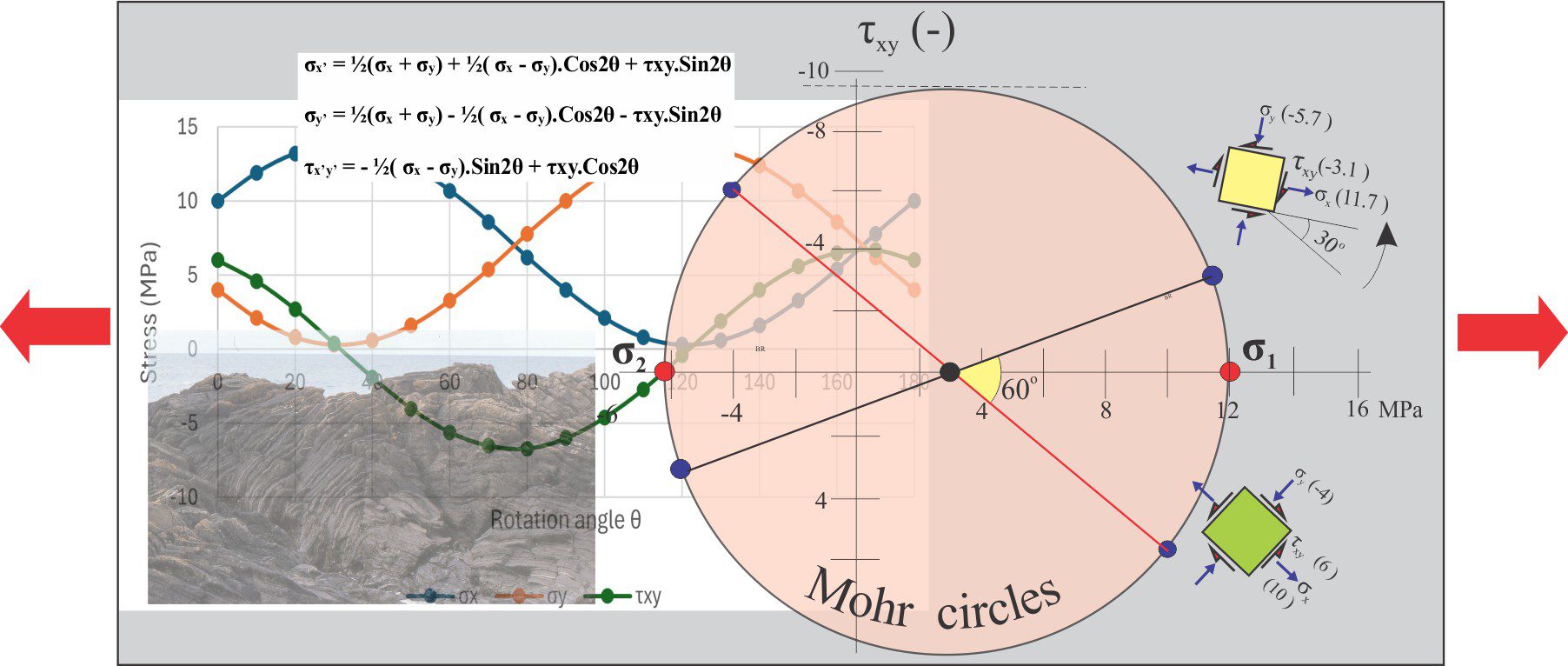

Stress (geology): In geology we generally recognise two kinds of forces: surface forces, and body forces such as gravity that act on every part of a sediment, rock, or fluid body. Thus, stress or pressure can be expressed as force per unit area for surface forces, and force per unit mass for body forces. In Earth science we consider stress at the microscopic, single grain or crystal scale up to the scale of entire lithospheric blocks.

Stretching factor: β is used in models of lithospheric stretching and rifting. It is the ratio of the stretched width of the crust-mantle lithosphere and original pre-rift width.

Strike: The compass bearing of an imagined horizontal line across a plane. It is at right angle to true dip.

Strike slip fault: A fault that displace rocks laterally, or along the strike of the fault plane. If you are looking at the fault from one of the displaced blocks, the sense of displacement is dextral if the opposite block moves to the right, and sinistral if it moves left. The term is synonymous with transcurrent fault and wrench fault. Cf. transform fault

Strike-slip/pull-apart/wrench basins: Elongate, rhomboid- or sinusoidal-shaped basins formed by extensional subsidence, most commonly at releasing bends or extensional fault stepovers. Strike-slip basins have high aspect ratios, and are relatively deep compared with their areal dimensions. Cumulative stratigraphic thicknesses can be >10km where shingling of dipping sedimentary panels keeps pace with fault-induced depocentre migration. Sediment composition may change over the life of a strike-slip basin because of lateral shifts in source rock.

Stromatolite: Biogenic structures consisting of laminated microbial or cryptalgal mats, that form distinctive mounds or branched structures. Laminae are flat to convex upward. Their relief above the sediment-water interface ranges from a few millimetres to several metres. The morphology of stromatolites is best seen in cross-section profiles. Precambrian examples consisted primarily of cyanobacteria; they are understood to be the first photosynthetic organisms that ultimately gave rise to atmospheric oxygen. See also thrombolite.

Strombolian eruption: Mild explosive eruptions of relatively fluid magma, that produce incandescent bombs, scoria and lapilli size fragments largely restricted to the cinder cone or volcano flanks. Fire fountains are small. VEI = 1-3.

Structure contours: Lines of equal elevation across a structural surface, such as an unconformity, stratigraphic unit, basement,and intrusive bodies.

Structure contour maps: Analogous to topography maps, they help define the extent and structural configuration of geological surfaces at depth. They are widely used in hydrocarbon and mineral exploration.

Structure grumeleuse: A term introduced by Lucien Cayeux in 1935, refers to clotted limestone textures where isolated, diffuse patches of micrite are surrounded by coarser neomorphic spar; the overall texture appears clotted. At times it can be difficult to distinguish between this recrystallisation texture and primary peloidal limestones.

Stylolite: Saw-tooth like, discordant seams that signify pressure solution of rock components (framework clasts and cements). They are most common in carbonates but can form in siliciclastic rocks. They represent differential compressive stresses at grain-to-grain contacts, the dissolution and mass transfer of carbonate by diffusion and fluid flow. Stylolites commonly parallel bedding (from normal compressive stress) but also form oblique to bedding.

Subaerial unconformity: In sequence stratigraphy, subaerial unconformities develop during regression and sea level lowstand, and for at least some of the subsequent transgression until the shelf is completely flooded. The shelf or platform is exposed to erosion and meteoric diagenesis. The hiatus is least at the final position of the shoreline, and greatest landward. They are generally considered to be chronostratigraphic surfaces. They are sequence boundaries.

Subaqueous dunes: Any ripple or dune-like bedform that forms in flowing water. An SEPM workshop in 1987 attempted to revise crossbed terminology, by incorporating the 3-dimensional aspects of bedforms larger than common ripples, with their inherent hydraulic properties. They recommended that the term dune be used, with the basic distinction between subaerial and subaqueous dunes, of all sizes. Subaqueous dunes were separated into:

- 2 dimensional subaqueous dunes having relatively straight crest lines and planar foreset contacts; they correspond to tabular crossbeds, and

- 3 dimensional subaqueous dunes having sinuous crest lines and spoon- or scour-shaped foreset contacts. These correspond to the classic trough crossbeds.

Subcretion: Slices of sediment and shallow crustal rocks that are accreted to the base of crustal slabs or accretionary prisms during compression, usually associated with subduction.

Subcritical flow: Defined by Froude as the conditions in surface flows where inertial forces dominate and Fr<1. It corresponds to lower flow regime bedforms such as ripples and larger dune structures, that usually are out of phase with surface waves. Also called tranquil flow. cf. antidunes, supercritical flow.

Subduction zone: Subduction zones are the ‘recycle bins’ of oceanic lithosphere. Cold, dense oceanic lithosphere will sink beneath less dense continental lithosphere at convergent plate boundaries, whereupon it is recycled into the mantle. The process may also be initiated by the negative buoyancy of the dense, oceanic rock, sinking under its own weight. The subducting plate was first identified by dipping zones of earthquake epicentres beneath island arcs and convergent continental margins, such as the Andes; these are Benioff Zones. Epicentres as deep as 640 km have been recorded.

Submarine canyon: Like their terrestrial counterparts, they are narrow, deep, steep sided valleys that extend from a continental shelf or platform to the slope, terminating near the base of slope or rise, where they merge with submarine channels. Their location may be structurally controlled, initiated by paleodrainage, or focusing of sediment gravity flow during low sea levels. They are important conduits for sediment delivery to submarine fans. Canyon wall collapse may produce significant tsunamis. Canyon heads may approach within a few 100 m of shorelines (e.g. Monterey Canyon, California, Hikurangi Canyon, New Zealand).

Submarine fan: Fan-shaped depositional systems that accumulate at the base of slope, continental rise and adjacent basin floor. Sediment is usually fed via a large submarine channel or canyon that may bifurcate into multiple channels down gradient. The channels feed sediment to lobes that prograde basinward; lobes may be inactive for a period. Deposition is dominated by sediment gravity flows – turbidity currents, debris flows. Mass transport deposits (slumps, slides) are common in some fan systems.

Submarine gullies: Like their terrestrial counterparts, gullies are steep sided depressions that form where there is an abrupt change in slope, typically at the marine shelf-slope break. They can form by erosion via some pre-existing depression, or by slope failure. Gullies become the focus for transfer of sediment from the shelf-platform to the deeper basin.

Subtidal zone: A nebulous term for the sea floor below mean low tide. It includes the shoreface and the littoral zone.

Successor basins: Post orogenic, relatively undeformed basins that overlie fold belts and terrane suture zones. The timing of successor basin fill helps bracket the end of (exotic) terrane accretion, or docking (e.g. by plate collision). They usually consist of terrestrial sediments, the provenance of which will reflect the compositions of the lithospheric blocks involved in terrane accretion.

Sunspots: Temporary darkened areas of the Sun’s surface that represent reduced temperatures, caused by local changes in the solar magnetic field. The number of sunspots waxes and wanes on an 11 year cycle (Schwabe cycles). They cause changes in solar output of about 0.07%. Galileo was one of the first to record the size and variability of sunspots.

Supercritical flow: Defined by Froude as the conditions in surface flows when gravitational forces dominate (over inertial forces) and the Froude number Fr > 1. The corresponding stream flow surface conditions manifest as an acceleration of flow such that stationary waves (critical flow) break upstream forming chutes. This corresponds to upper flow regime conditions. cf. subcritical flow.

Supercritical liquid: A liquid that has properties somewhere between a gas and a liquid. For example, for CO2 these properties include high solubility in oil and water; density similar to the liquid phase but much lower viscosity – the latter property enhances flow through pipes (transport)and through porous rock; low surface tension.

Superterrane: The composite of two or more terranes that were amalgamated prior to its accretion to an orogen.

Supratidal zone: The region above spring tides that is inundated only sporadically by storm surges. On low relief coasts it can be an extensive flat, including salt marsh, or sabkhas in arid climates. On high relief, rocky coasts it refers to the splash zone that is rarely inundated by tides.

Surface waves (seismology): Seismic waves generated by impulses, such as earthquakes, that travel across Earth’s surface. They are slower than P & S waves (body waves) but commonly are higher amplitude (i.e. the amplitude of surface motion). On seismograms they arrive after P and S waves.

Surtseyan eruption: Violent explosive eruptions caused by the interaction of magma with sea-lake water or groundwater. These are primarily phreatomagmatic eruptions. Eruption columns reach a few 100 metres. Eruptions are a continuous series of jets that can last for weeks, gradually building tephra cones and rings. Named after Surtsey (Iceland), 1963).

Suspect terrane: The evocative name given to any terrane, particularly those of unknown or indefinite origin. Generally synonymous with exotic terrane and allochthonous terrane.

Suspension load: The part of the sediment load held in suspension in water or air by turbulence and buoyancy. See bedload

Swamp: A wetland in freshwater or coastal (paralic) seawater environments that has a vegetation cover dominated by trees (cf. marsh).

Swash zone: The portion of a beach subject to wave run-up. Run-up velocity depends on the momentum produced by breaking waves and the beach gradient. It is usually sufficient to move sand and shells, and remove fine-grained sediment. Cf. Backwash.

Symmetric ripples: Bedforms on which the accretionary faces, or foresets, have equal or similar slope – in profile they appear symmetrical. Wave-generated ripples are commonly symmetrical because of the passage of wave orbitals, where the front of the orbital flows in the opposite direction to the orbital rear.

Syncline: A convex upward or inward fold in which layers are younger toward the centre of the fold. Cf. synform, anticline.

Syndepositional processes: Strictly speaking, processes that take place during sedimentation, although the term is often extended to include processes ‘soon after’ deposition. Common examples are deformation that influences sedimentation (syndepositional faulting, slumping), geochemical processes such as sea floor cementation, and biogenic activity. A common synonym is synsedimentary.

Synform: Concave upward folds where the stratigraphic younging or facing direction is unknown. Cf. Syncline, antiform.

Synoptic relief: The relief above the sediment surface of an actively growing cryptalgal or microbialite mat. In stromatolites, each lamination represents a period of growth at the sediment surface – the maximum amplitude of these concave upward mats is the synoptic relief, or growth relief. Synoptic relief is commonly no more than a few millimetres but can be as high as 4-6 m in large, platform margin stromatolite reefs or buildups.

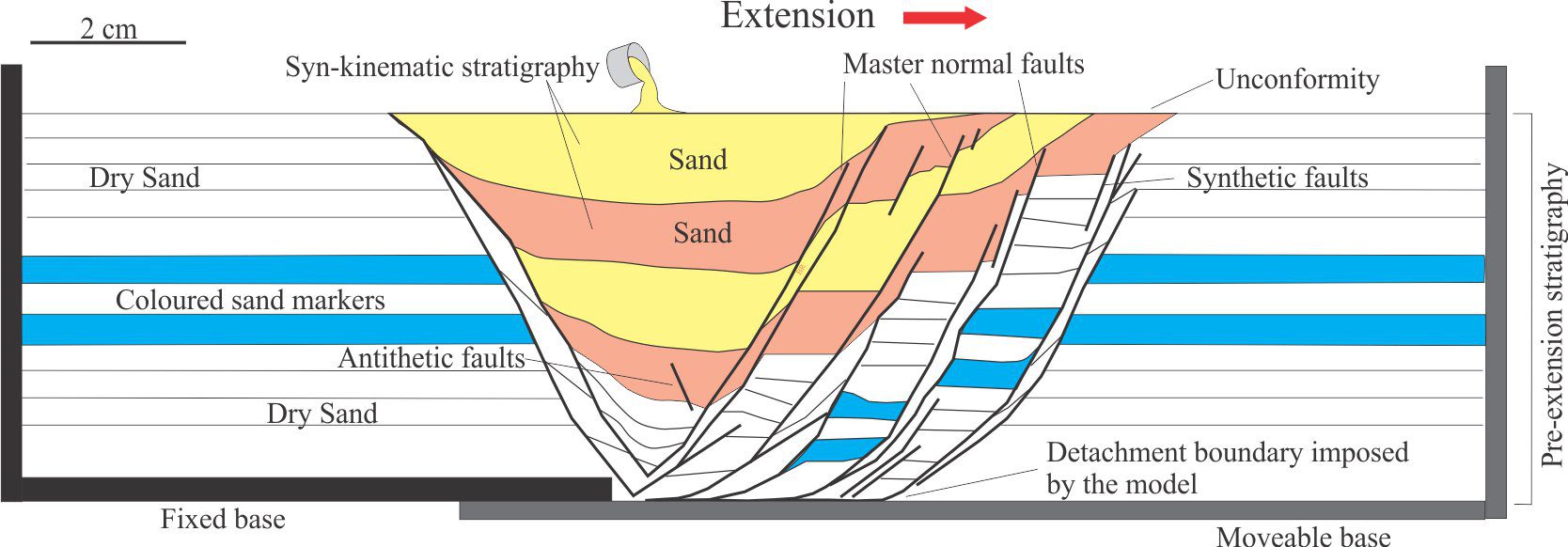

Syn-rift: At the time of rifting. It is usually applied to structures such as listric faults that develop from brittle failure during crustal stretching, and to the sedimentary deposits that accumulate during the various rift processes particularly deformation and volcanism, commonly in fault-bound basins. Cf. Post-rift.

Synrift subsidence: The initial, rapid stage of subsidence resulting from lithospheric stretching, thinning, and faulting. The amount of subsidence attributed purely to these tectonic processes is determined by backstripping. cf. postrift subsidence, geohistory.

Syntaxial overgrowths: Crystals that have grown on, and are in optical continuity with a substrate (of the same composition) are referred to as syntaxial overgrowths or cements; i.e. they share the same optic axis (the term epitaxial is also used in this sense by some, although the International Mineralogical Association insists that in epitaxy the overgrowing phase is mineralogically different to the substrate). Well known examples involve quartz overgrowth cements in quartz arenites; in many cases the original grain outline is distinguished by a rim of inclusions. In limestones, echinoderm plates commonly have syntaxial calcite overgrowths. In polarized light and crossed nicols, both the overgrowth and original grain move into extinction together.

Synthetic faults: See antithetic fault

Systems tracts: Systems tracts consist of depositional systems that are contemporaneous and genetically linked. They contain relatively comfortable stratigraphic successions (i.e. no major unconformities). When first used in sequence stratigraphy by Vail and others (1977) they were conveyed as representing positions on a eustatic sea level curve. The terms Highstand, Lowstand, Transgressive, and Falling Stage, and Regressive systems tracts are now associated only with relative sea level. Systems tracts can be used at any scale.