I had the good fortune to work in the Atacama volcanic region a few years ago. It may be the closest I get to walking in a Martian landscape (NASA tests its Mars rovers there)

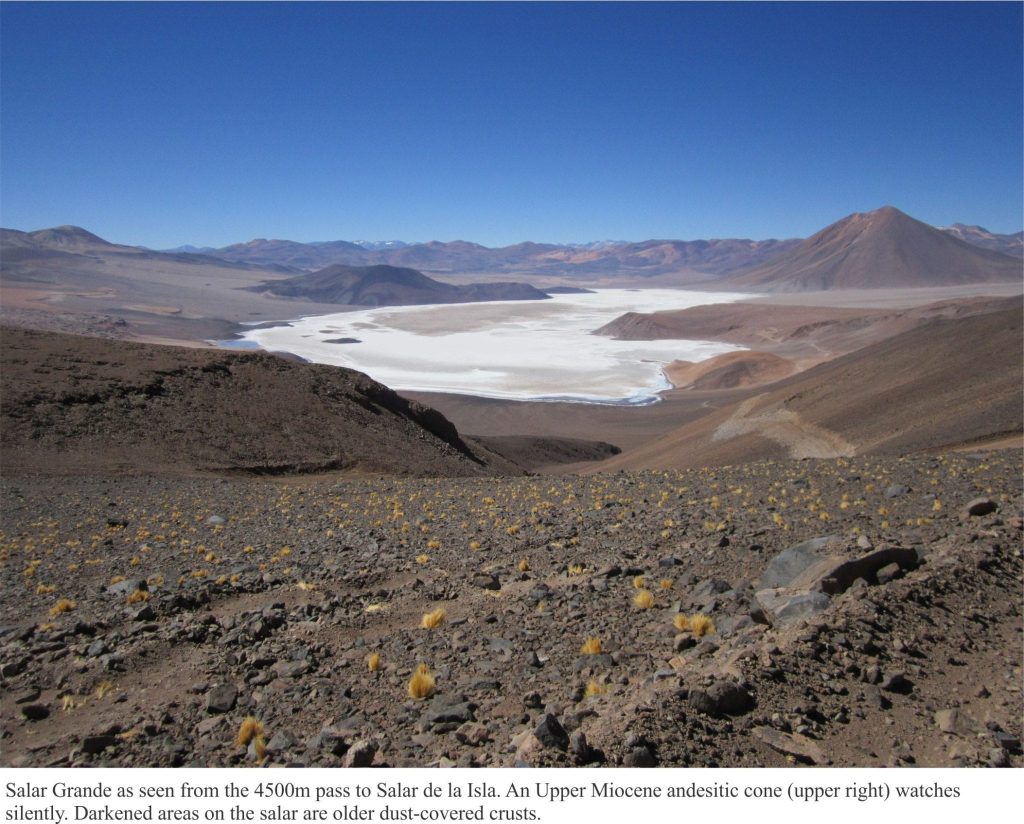

The mountains of Atacama, also known as the Altiplano-Puna Plateau, is one of the driest places on earth; it is located inland from the coastal Atacama Desert. A parched landscape littered with volcanoes, valleys where the few toughened blades of grass eke out a living, and salars, the salt lakes where there is barely a ripple. The salars are a kind of focal point for local inhabitants – Vicuña that graze on spring-fed meadows, flamingos that breed on the isolated breaks of open water, and foxes that lie in wait for both. It is a harsh environment, but stunning; glaring snow-white lake salt against a backdrop of reds and browns. And overhead, crystal skies, fade to black.

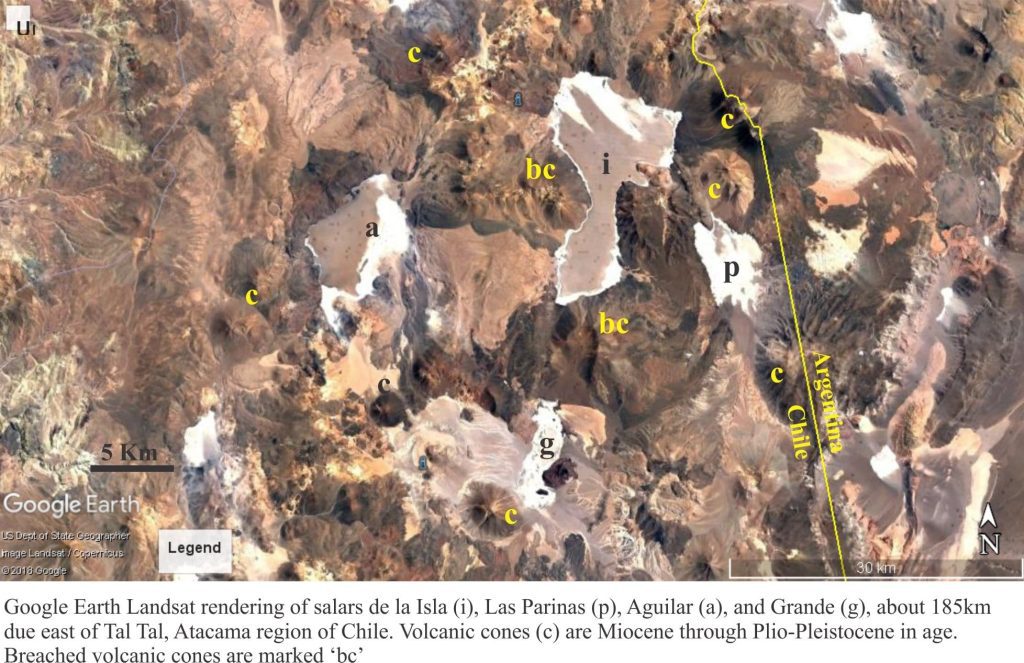

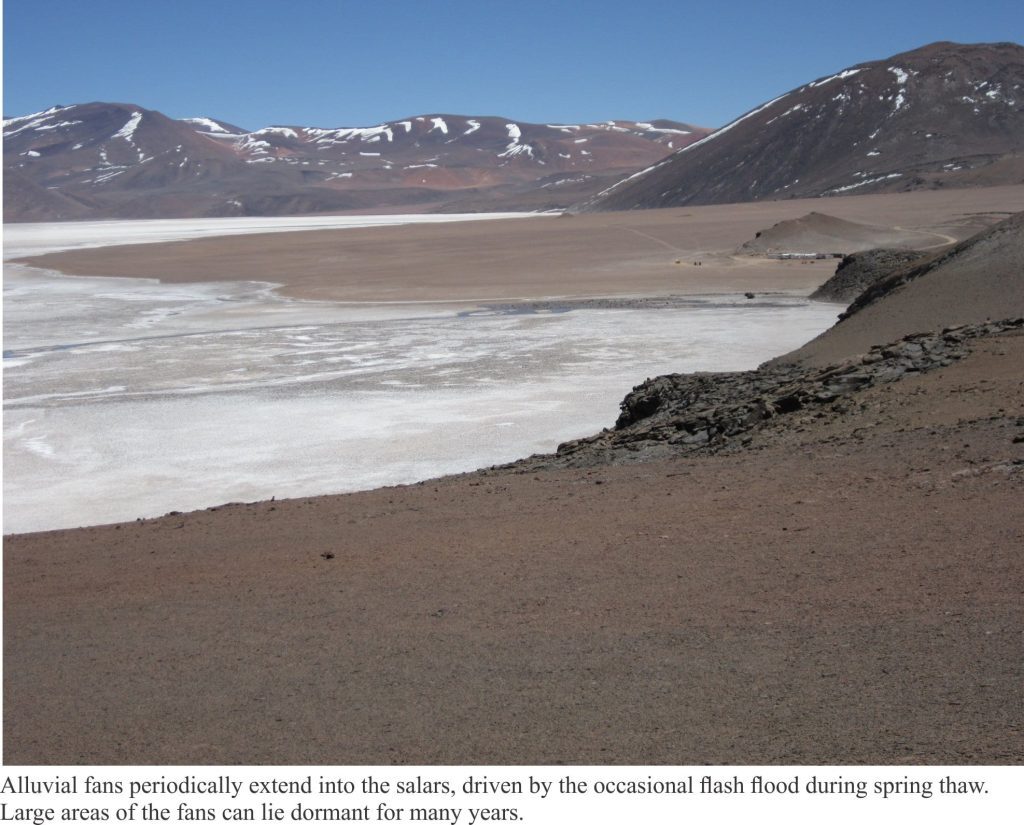

Take as deep a breath as you can – you’ll need it. Most of Atacama’s mountain salars are about 4000m elevation. The salars are saline lakes, their surfaces covered by a thick crust of precipitated salts. Salar de la Isla and its immediate neighbours, La Grande, Las Parinas, and Aguilar (the salars I am familiar with) are endorheic basins – basins that are enclosed by rocky terrain with no natural drainage outlet. Here, the drainage basins are hemmed by volcanic cones, lava flows and ashfall deposits, and ancient lahars that tell of a time when precipitation may have been more frequent. Volcanic cones peak at 5700m; some are as old as 20 million years (Early Miocene) and yet look like they formed yesterday. They stand guard over the salars, occasionally sending boulder torrents (lahars) down steep slopes to fringing alluvial fans; In the geological past, lahar tongues have sped across the salar salt.

Fresh water enters these basins in two ways: surface runoff during the brief spring thaw, and groundwater seepage. Of the two, groundwater seepage probably contributes a far greater proportion of new water to the salars. Snow pack does develop over the winter months, but during the thaw most of the meltwater evaporates or seeps into the rocky soils and bedrock fractures. Some surface water is involved with flash-flood debris flows across the many alluvial fans.

Groundwater seepage to the salars is a more or less continuous process, even during the frigid winter. The source of water is the elevated topography bordering each salar. Seepage is visible along the lake shores, occasionally ponded, supporting green algae or patches of grass that are a welcome sight for Vicuña It is likely that seepage also takes place at depth in the salars, beneath the salt carapace.

Fringing alluvial fans poke their noses into the salars, recycling and redistributing volcanic debris during flash floods. There is a kind of interplay between the salars and alluvial fans. When lake levels are low the fans encroach farther offshore; when levels rise the salt flats move onshore. These kinds of cyclical changes probably occur over intervals of 1000s to tens of 1000s of years.

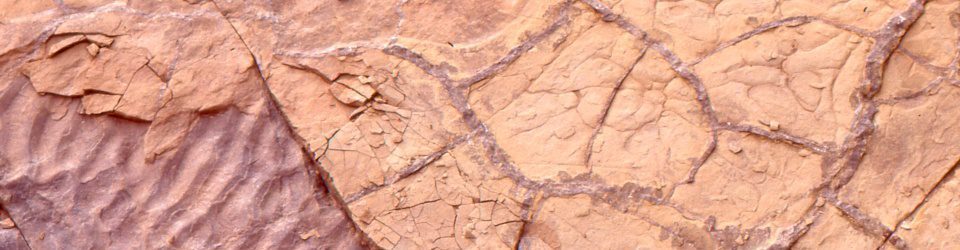

Water entering the salars is exposed to intense evaporation. Average humidity in many parts of inland Atacama Desert is close to nil; this is the case for the large Salar de Atacama south of San Pedro de Atacama, at 2305m elevation (this salar is currently mined for lithium). Humidity levels in the rugged, volcanic part of Atacama are probably similar. The incoming groundwater has low concentrations of dissolved calcium and sodium minerals derived from the surrounding volcanic rock and possibly from local geothermal activity, that becomes more concentrated during evaporation. At a certain point in this process (that in the jargon of chemistry is called saturation), gypsum (CaSO4) and halite (NaCl – common salt) precipitate as crystalline masses – gypsum first, and then halite as the brine becomes more concentrated. The precipitated salts form a jagged surface of filigree crystal forms, partly moulded by wind and dust.

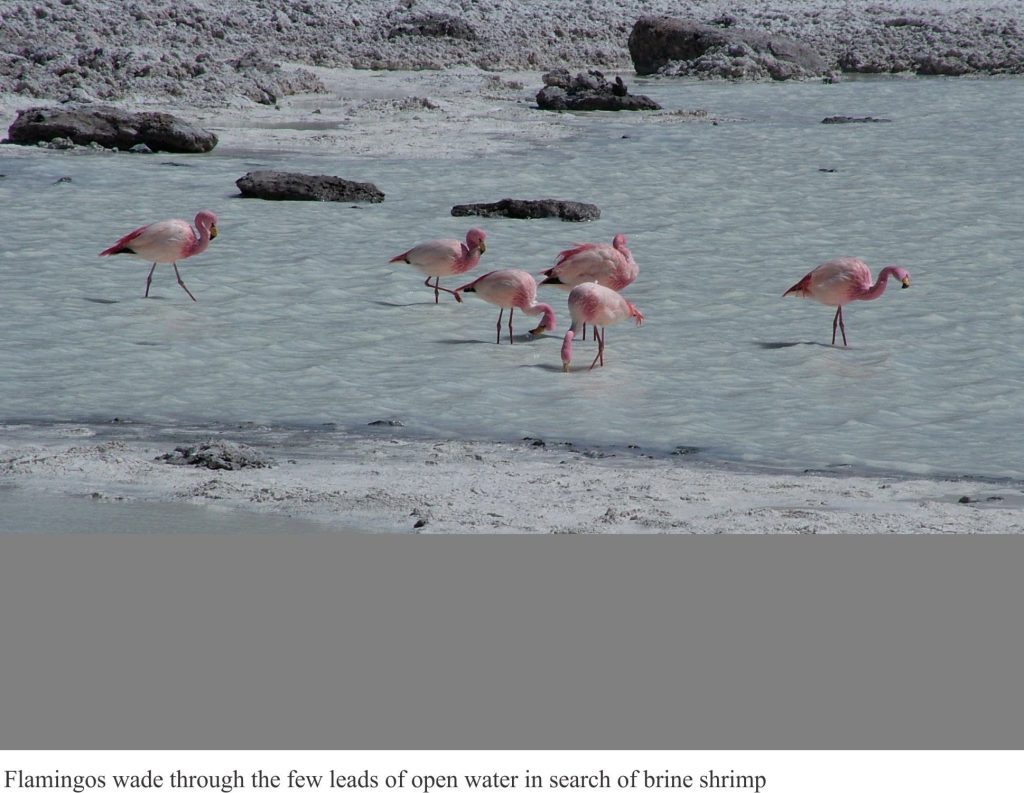

Areas of open water are few. They tend to form where upwelling brines or springs prevent the growth of a rigid crust. In summer, they are favourite haunts of flamingos that come to breed. When they arrive, the flamingos have greyish plumage; after a summer’s diet of brine shrimp, they depart in a spectacular flurry of crimson wings.

Working in the Atacama mountain region is a treat, although it can be arduous. Air pressure at this level is 60% of that at sea level which means that each breath is about half as effective in terms of oxygen availability. A person can acclimatize to these conditions over 2-3 days, but headaches and nausea are common. However, for some folk altitude sickness can be severe. The symptoms are in large part brought on by reduced kidney function, as the organs try to regulate body fluids and electrolytes.

The UV Index is also perpetually at an extreme level. At 4000m, incident UV light is 40-50% more intense than at sea level. The expanse of salt, like snow, exacerbates the exposure.

I generally found early morning runs were out of the question. Scrambling even the lowest slope usually required a few rest stops. The motivation for rapid physical movements dissipates as quickly as the available energy levels. Frequent rests and even the odd lie down, are a sensible approach to working at these elevations.

Just make sure you choose a spot with a good view when taking a breather.