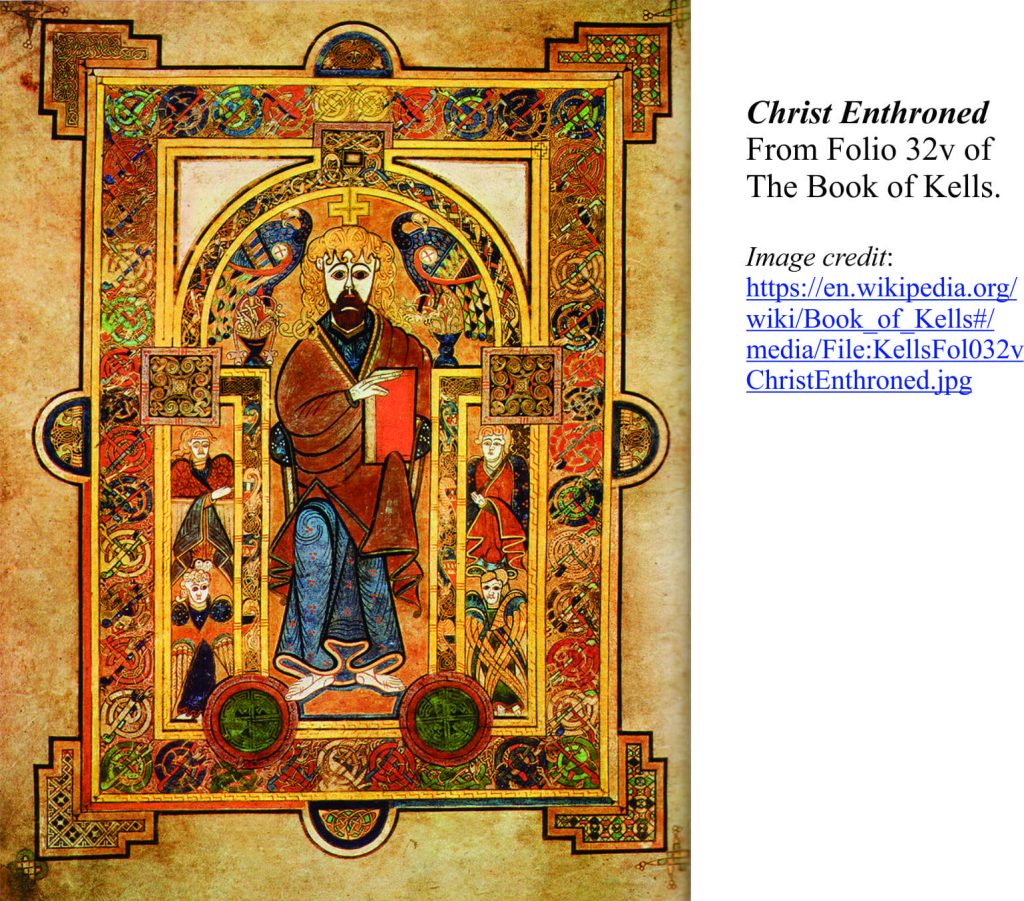

A chance encounter of a different kind. The 9th century Book of Kells is exhibited in the Trinity College library (Dublin). The book contains 340 sumptuously illustrated folios written on vellum (calf skin), that make up the four Gospels (the entire book can be viewed online). It was written and illustrated around 800AD, in either Iona (Argyllshire, Scotland) or Kells (County Meath, Ireland), and possibly both. Monks from the St. Colum Cille Monastery in Iona, fled to Kells in 806 to evade further slaughter by marauding Vikings (who seemed to have a penchant for religious orders). Hence the uncertainty surrounding the location of the Book’s compilation.

Two or three folios are exhibited at any one time in the library. There is something special about seeing this, regardless of one’s beliefs. That a document this ancient has survived pestilence, religious and political purges, plundering and the general ravages of time, is a testament to the enduring belief that human history is worth preserving.

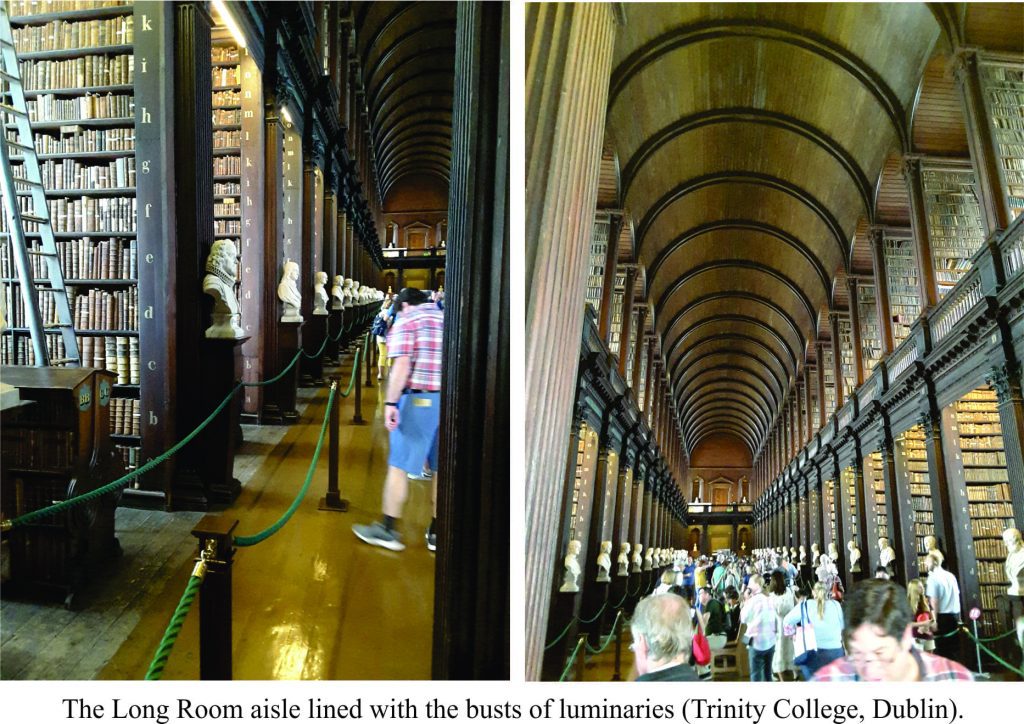

A visit to the Book of Kells exhibit eventually leads to the Long Room, a cathedral-like hall with high barrel-vaulted ceiling dedicated to preserving old and ancient manuscripts, tomes, letters and assorted documents. It was first built in 1712) but enlarged in 1860 to accommodate a burgeoning collection.

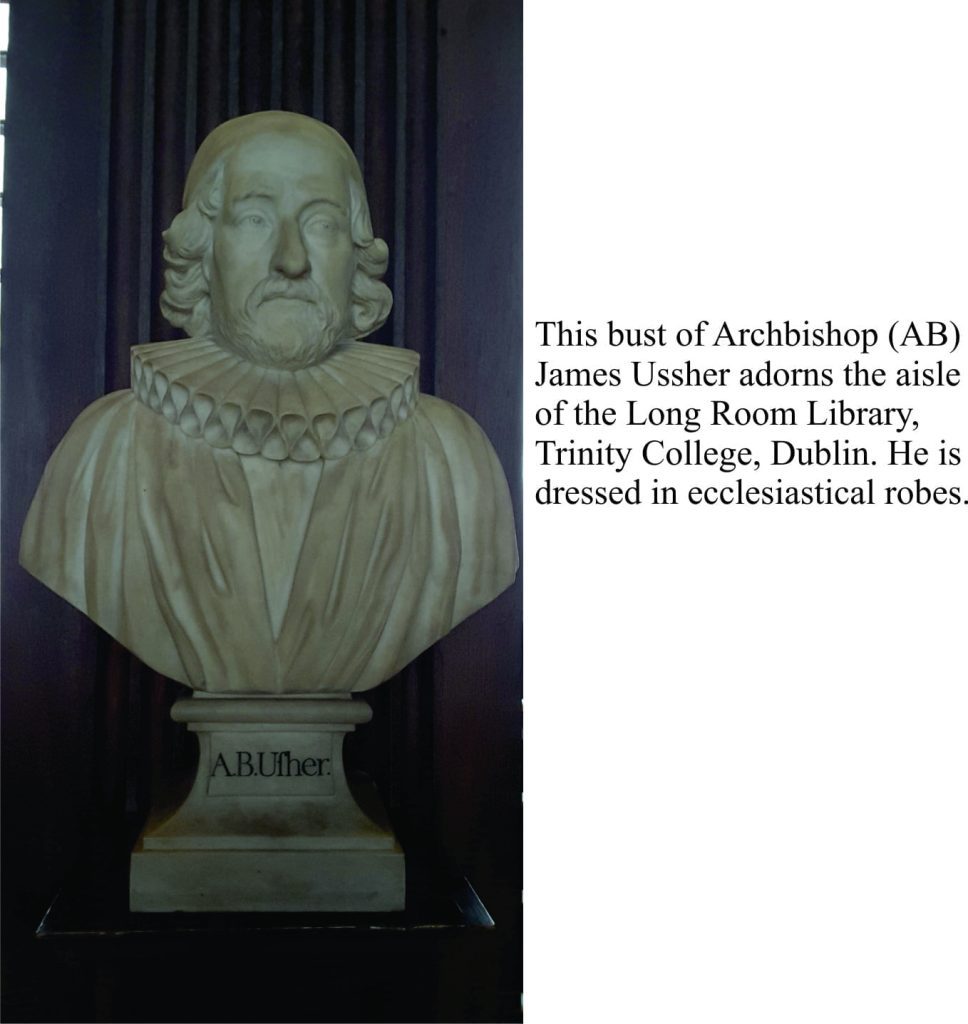

One of the College’s 17th century benefactors was James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh (although he never lived to see the actual Long Room). He was instrumental in purchasing books for the then nascent College library. Ussher became famous, or infamous, for his dating of Genesis creation at October 23rd, 4004 BC. He based this calculation (published in 1650) on biblical genealogies and historical events. Given what we now know about the age of the earth, Ussher’s calculation is generally viewed with a mix of ridicule and begrudging respect.

Acting on a hunch, I asked one of the library attendants if any of Ussher’s books were available for viewing. He suggested I check with the folk in charge of ‘reading room’ passes. This took a while but I was eventually issued a pass and ushered (sic) to the reading room. The first task was to search the catalogues. One index of books had an entry annotated with scribbled comments on “creation dates”. Bingo. This particular volume appeared shortly thereafter in its own protective box. A rather plain unassuming book was placed carefully on a special reading rack. Instructions were given on how to turn the thin, brittle, dog-eared pages.

The journey through 400 year old documents like these is more one of personal discovery than some momentous event of universal import. The book was a collection of Ussher’s notes, annotated texts, and the odd piece of correspondence. Flicking through these pages gave, for a moment, a view into Ussher’s thinking. Here were his working notes, in a mix of Latin and English. Marginal scribblings on printed text and fragments of scripture, ecclesiastical compositions, calculations of cumulative dates gleaned from the scriptural register of births and deaths, crossings-out and corrections. Here was a person, a Bishop of repute, who tried genealogical combinations, recognized errors, approximated, and perhaps even fudged the odd date. Maybe there were even doubts about the progression of time.

The opportunity to look at Ussher’s notes came out of the blue. It was worth the multiple forms I was required to sign, acknowledging Trinity College’s copyright. I took photos of the text, but cannot display them. What a shame. A 400 year-old document originally intended to be read by all and sundry, now (figuratively) locked away by some arcane law (unless I payed a fee). I don’t decry all copyright conditions, just this one, that applies to a document written by a person who probably never intended such conditions of ownership to apply.

We now know that Ussher’s date for the beginning of earth history has a rather large margin of error. As absurd as his date may sound, it was derived from serious scholarship, in a manner we would now call ‘multidisciplinary’. This in itself is something to celebrate.

Here is a slightly different take on Ussher’s scholarship

A very interesting post Brian. I forwarded it to my mom who is interested in such manuscripts.