Negotiating a passage through remnants of sea ice, beginning the 1977 field season on Belcher Islands.

Not really a CV, more a precis

1969 and about to begin a BSc at Auckland University, Aotearoa-New Zealand (aiming to major in chemistry), I needed one more paper to complete the first-year syllabus. A friend suggested I try geology – “isn’t that fossils, rocks, dirt and stuff?” “Yeah, pretty interesting though”. “That’ll do!” I had made my choice. At that time BSc geology consisted of 2 papers each year – one paper (imaginatively called Geology A or B – I can’t remember which) included all ‘soft rock’ topics (sedimentology, paleontology, stratigraphy, geophysics etc.), and the other paper mostly ‘hard rock’ topics (igneous, metamorphic, structure, crystallography etc.). Students were immersed in everything – there were no options.

So, I majored in geology and chemistry for my BSc (Auckland University), but my passion was geology.

Fast forward another 2 years and completion of an MSc (geology, Auckland University, 1975), with a thesis on the sedimentology and stratigraphy of Quaternary aeolian, shallow marine, and fluvial deposits in subtropical northernmost New Zealand. Much of the exposure was coastal so in between measured sections and samples, I collected shellfish or threw out a fishing line to catch dinner.

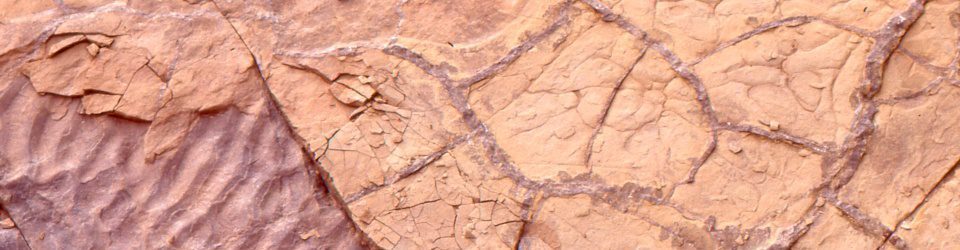

From 2 million years to 2 billion years: It’s now January 1976, confronted by a minus 25oC Ottawa, Canada, on my way to start a PhD at Carleton University. I’d never seen so much snow. My supervisor was to be Alan Donaldson, a Precambrian seds guru, who was pretty keen on me doing a thesis on the sedimentology and stratigraphy of a Paleoproterozoic succession on Belcher Islands, Hudson Bay. This collection of elongate, squiggly islands is held up by a 7-9 km thick, 1.8 to 2 billion year-old succession of stromatolitic platform carbonates, shallow marine siliciclastics, a banded iron formation, a turbidite succession, red beds, and two spectacular volcanic successions. When I asked Al which formation I should work on he said “do the whole shebang“. Ok! A tough working environment but great exposure of fabulous rocks (lots of boat – Zodiac work over 0oC seawater and inclement weather – my assistant and I wore life jackets so that, we were told, they could find our bodies for insurance purposes). Al was a great supervisor.

So over two 10-week field seasons (1976-77) I measured 20,000 m of section, 2000 paleocurrent directions, and a slew of petrographic analyses. I defended in June 1979.

Next stop Calgary for a two-year stint with Gulf Canada Resources, then in 1981 landed a job with the Geological Survey of Canada. In the GSC Calgary office most of that work was centred on field mapping and stratigraphy-sedimentology of Upper Cretaceous – Paleogene clastic sediments on Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg islands – mostly shallow marine, fluvial and delta settings. There were other bits and pieces in the Alberta Front Ranges, Yukon, and Mackenzie River. A move to the GSC Vancouver office in 1989 saw the emphasis change to Mesozoic sedimentology of one of the largest Intermontane basins in British Columbia, Bowser Basin, a foredeep with sediment derived from an obducted slice of oceanic crust.

Between 1992 and 1993 I realized I needed a change in Earth Science emphasis, and a logical choice was hydrogeology where I could use my knowledge of sedimentary rocks (sediment body geometry, composition, porosity-permeability and so on) and geological mapping to characterize fluid flow at both a basin-scale, and near-surface groundwater aquifer scale.

This culminated in a 4-year GSC pilot project to map and characterize aquifers in the greater Vancouver – Fraser Valley – Delta region of southern British Columbia, coordinating the expertise of colleagues with the use of shallow reflection seismic, ground penetrating radar, electromagnetics, gravity, MODFLOW modelling, and GIS data management of water-well databases and subsurface aquifer maps. Inserted between these programs was a brief secondment to the Hungarian Geological Survey in 1992 to help develop their basin analysis projects.

I quit the GSC in 1997 and moved with my Canadian family back to Aotearoa – New Zealand to work a 4-year teaching stint at University of Waikato, working primarily on Late Miocene – Pliocene siliciclastics and cool-water carbonates in Whanganui Basin (west North Island). From there a part-time position at Auckland University, teaching post-graduate basin analysis and undergraduate hydrogeology, and supervising (mostly) groundwater-related theses. But this position also required a significant weekly commute, and with an evolving disenchantment of academia I decided to form my own consulting company in 2005 – a company of one – and never looked back!

As a consultant I worked lots of NZ coal and oil-gas well-site geology (yes, I know…!), geothermal hydrogeology (Taupo region), basin-scale CO2 sequestration evaluation (with GNS), lithium-bearing brines in the Chilean Altiplano (base camp at 4000 m – the geology here is amazing), and a bunch of smaller jobs mostly groundwater-related. I loved this stage of my life – I was my own boss!

Now I am retired, tending to our organic kiwifruit orchard – we’ve been at it 25 years (all fruit exported so keep an eye open for it on your supermarket shelves), and maintaining the geoscience website that you must have linked to because you are reading this.

So, almost 50 years as a geologist. Time during 40 of those years was also spent as Editor and Associate Editor, mostly for the Canadian Society of Petroleum Geology and the SEPM including 8 years on the SEPM Council, and reviewer for dozens of journal papers. I still get requests for paper reviews, but I politely decline, noting that it is someone else’s turn.

Would I do it all again? Damned right, although I would probably try to insert a chapter on planetary geology into that life.