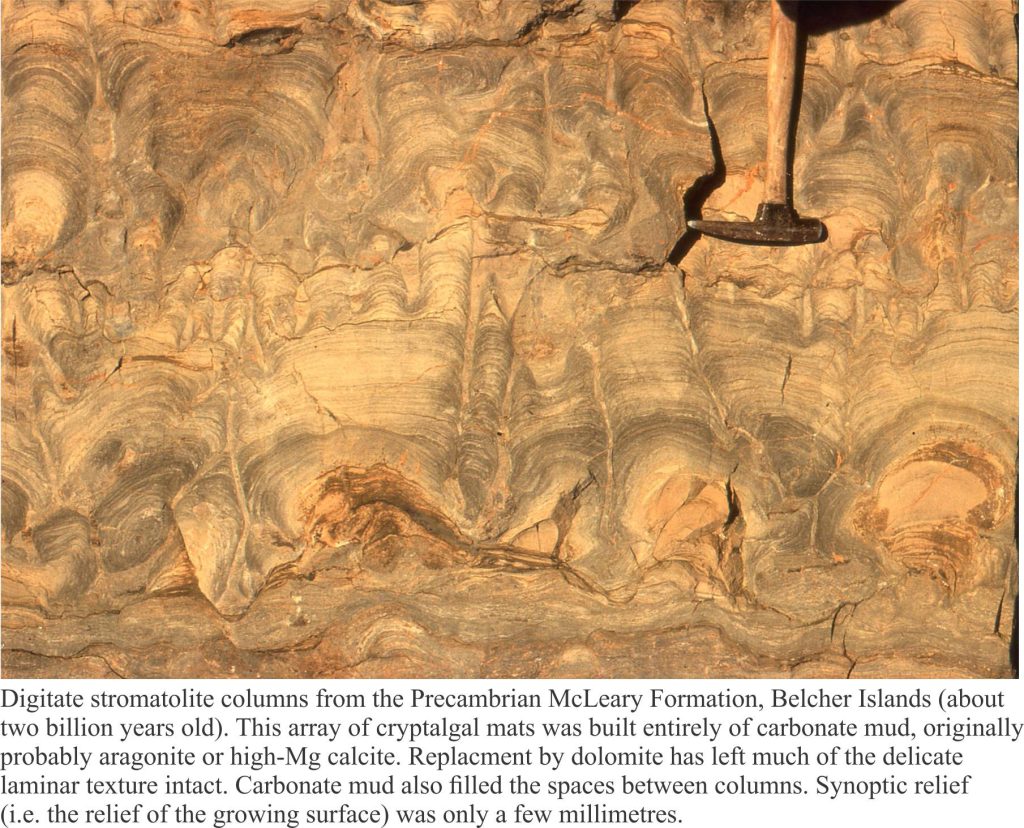

An example of a Paleoproterozoic stromatolite reef

This is part of the How To…series on carbonate rocks

Reefs are the largest biological constructions on Earth. They are ecological powerhouses, domicile to a multitude of invertebrates and vertebrates, algae and phytoplankton, all playing their part in acts of communion, competition, and symbiosis.

Reefs are also geological constructions:

- Modern coral reefs, and most reefs since the beginning of the Cambrian (541 million years ago) have rigid frameworks of corals, stromatoporids or rudists.

- Reefs fringe islands, platforms and continents.

- They range in size from small, isolated pinnacles and oceanic atolls, to extraordinarily large barrier systems; Great Barrier Reef extends about 2300km along the eastern coast of Australia.

- Reefs act as baffles to ocean waves. Waves support reef life by constantly refreshing oxygen and nutrients, but they can interrupt progress during damaging storms.

- Reefs have a partnership with lagoons.

These are the reefs we are most familiar with. They even evoke romantic notions, the splendours of nature; diving amongst brilliantly coloured corals and fish, home to apex predators, ships dashed upon… etc.

Earth’s earliest reefs looked quite different. For almost 3 billion years, Precambrian reefs consisted of stromatolites, constructed by micro-organisms; primarily cyanobacteria. They lacked rigid frameworks – most were susceptible to erosion, although sea floor cementation might have rendered them crusty. There were no grazing invertebrates – the ecological web must have been much simpler. Despite these fundamental differences, Precambrian reefs occupied and responded to similar oceanographic conditions as their Phanerozoic cousins:

- Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic prokaryotes which means the buildups accumulated within the photic zone, responding to changes in filtered light and seawater temperature.

- Stromatolite reefs defined platform margins, sometimes extending across entire platforms and shelves.

- Lagoons, tidal flats and sabkhas were partnered with the offshore buildups.

- Reefs that developed on platforms or shelves were usually associated with deeper water slopes that deposited hemipelagic material plus any coarse-grained shallow water sediment that bypassed the reefs. Slope facies may include mass transport deposits (slumps and slides, turbidites and debris flows).

- Stromatolite reefs and associated platform facies responded to fluctuating sea levels.

- Extensive buildups acted as baffles to waves and currents, and in turn were moulded by these forces.

- They were occasionally battered by storms.

- They were long-lived constructions. Large reefs probably represent hundreds of thousands and even millions of years accumulation.

Stromatolite reefs of the Mavor Formation

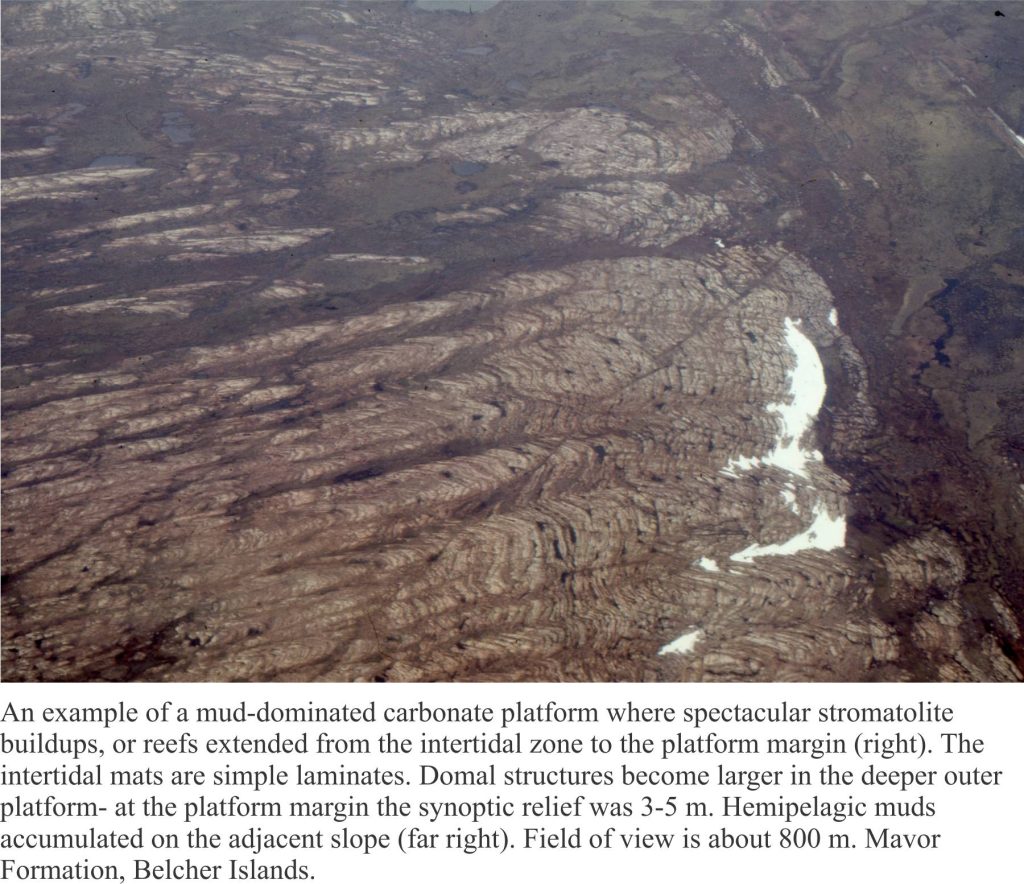

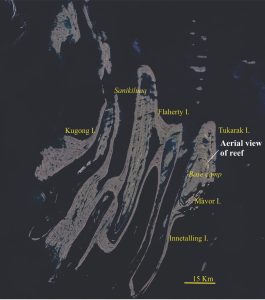

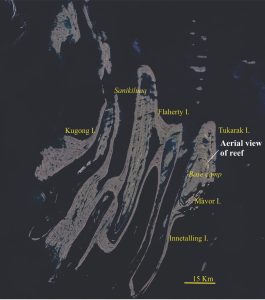

LANDSAT’s view of Belcher Islands (north at top). The aerial view (above image) is from Tukarak Island. Image credit: NASA, Jesse Allen, University of Maryland.

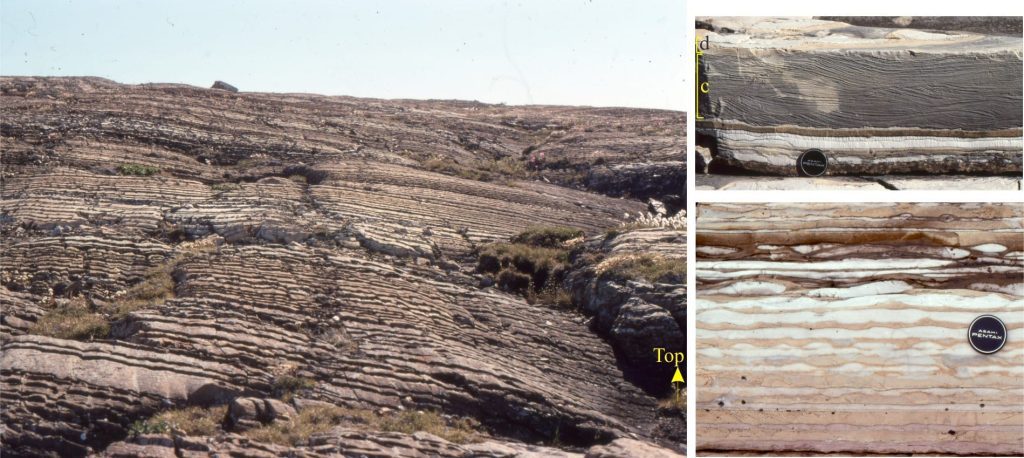

The Paleoproterozoic succession on Belcher Islands (Hudson Bay, Canada) contains carbonate platforms replete with stromatolites and cryptalgal laminates. One stratigraphic unit, the Mavor Formation, contains spectacular mounded buildups. One of the best exposures is shown below; here one can walk through a continuous succession, from beach to platform margin. The margin itself is delineated by an abrupt change in sedimentology, from large, high synoptic-relief stromatolitic buildups, to thin bedded, carbonate-rich rhythmites and shale deposited on the seaward slope. Slump packages and turbidites do occur but are not common. A few small, isolated stromatolites domes grew on the upper slope (i.e. outboard of the platform margin) – this probably reflects the maximum limit of the photic zone. The platform margin is a mappable boundary; slope deposits belong to the Costello Formation. The stratigraphic thickness of the reef package in the aerial view is 244m.

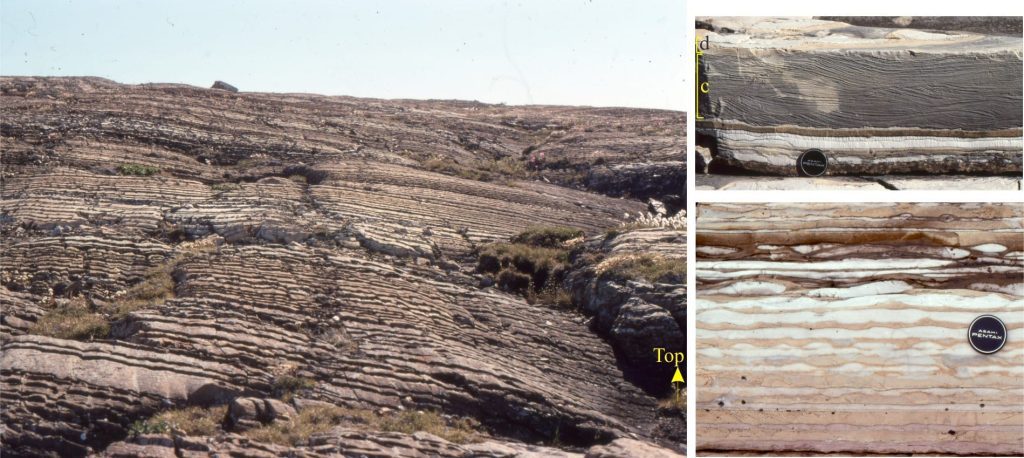

One of the better aerial views of the stromatolite reefs and platform margin (dashed line), east Tukarak Island. The horizontal distance across the buildups (left to right) is about 800m; beds dip right (east) 10o-15o. Buildup stratigraphy is 244m thick. Small subtidal mounds (left) coalesce towards the outer margin into larger buildups. Locations (a) through (d) refer to the 3D reconstructions shown below.

Shallow water facies

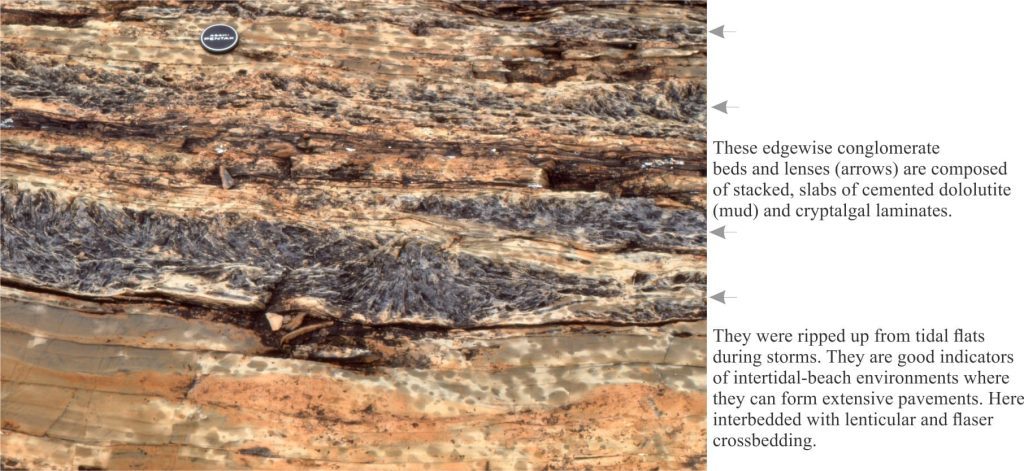

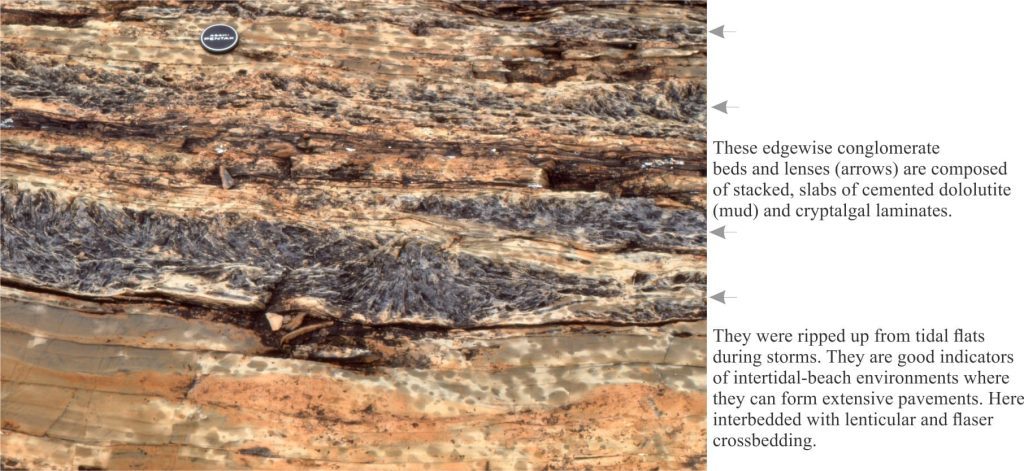

Depending on location, the landward part of the platform changes from sandy beach to intertidal-shallow subtidal flats. Facies indicative of beach settings include crossbedded grainstone, edgewise conglomerate pavements, and beachrock. Typical tidal flat structures are lenticular and flaser cross bedding, plus indications of prolonged exposure with mud cracks and gypsum crystals (replaced by dolomite). Local clusters of branched stromatolites and laminates show frequent scouring and reworking by storms.

Cross-section of tabular beds and lenses of edgewise conglomerate, interbedded with lenticular crossbedded grainstone. Conglomerate slabs consist of early cemented carbonate mud and cryptalgal laminates, probably ripped up during storm surges. Bedding views of the conglomerate show them to have formed extensive pavements.

Reef transitions across the platform

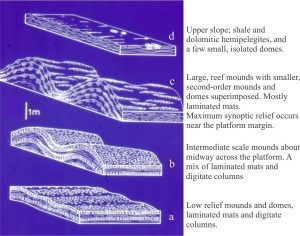

Three-dimensional reconstruction of Mavor platform mounds, from shallow subtidal laminates at the base, to high relief mounds at the platform margin. The stratigraphic section corresponds to that shown in the aerial view. Total stratigraphic thickness here is 244m.

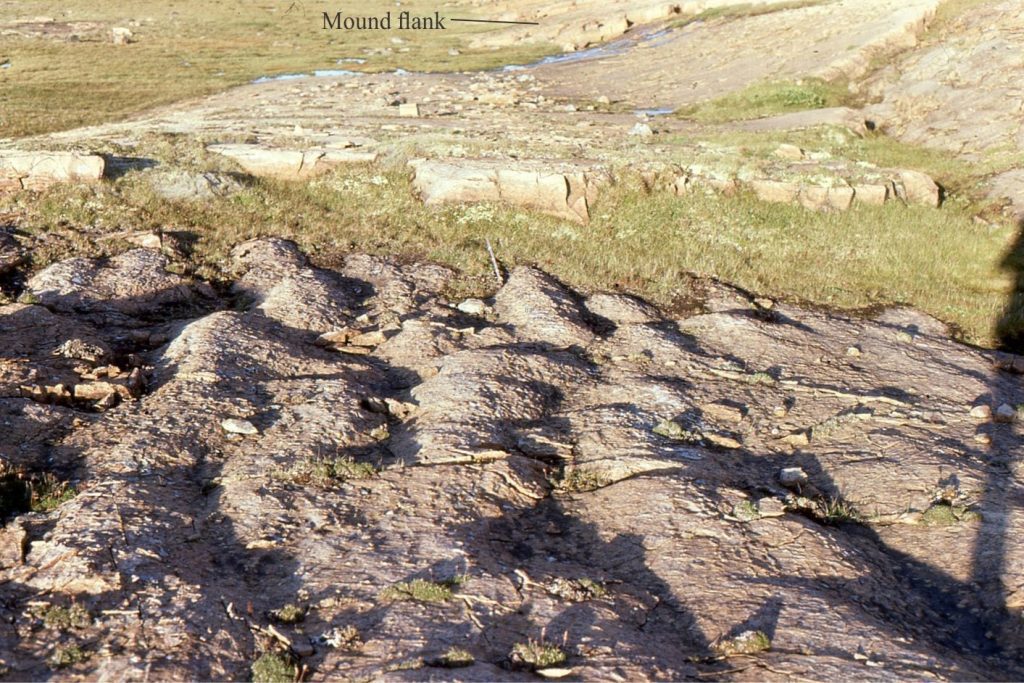

In the image above, the four panels reconstructed from field sketches and photos, show the stratigraphic changes in buildup organization. Beyond the beach, shallow subtidal mounds are relatively small, have synoptic reliefs of a few centimetres, and consist of laterally linked hemispheroidal domes and columns. Mounds are elongate, parallel to the overall trend seen in the aerial view; elongation direction is normal to the paleoshoreline, the strike of which was established from bedform azimuths.

Shallow subtidal, relatively simple, laterally linked and bridged mounds with synoptic relief of a few centimetres.

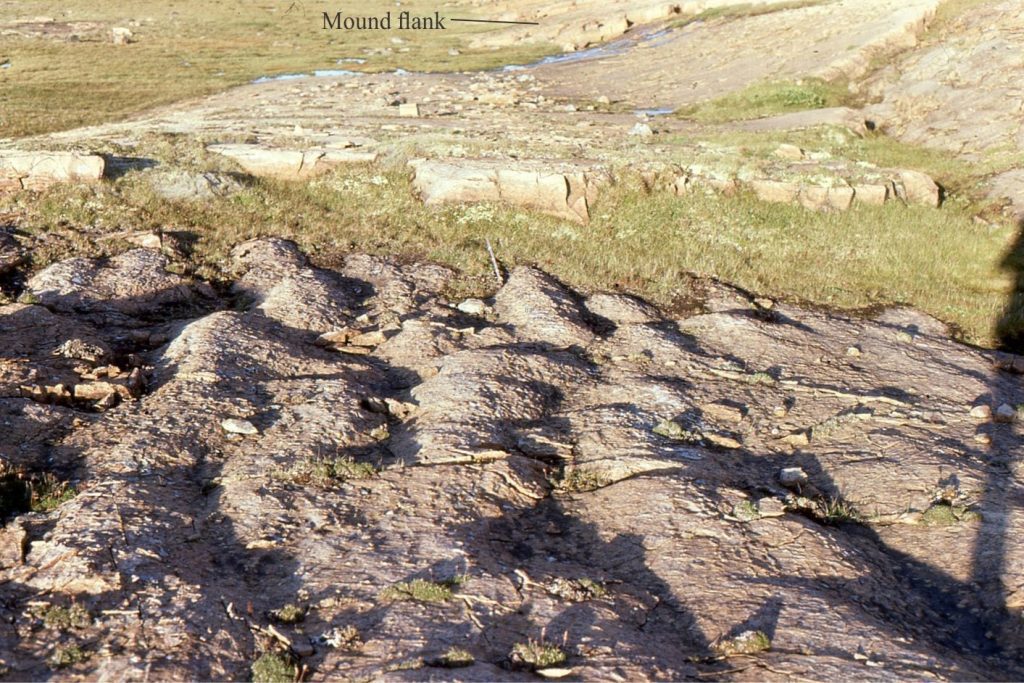

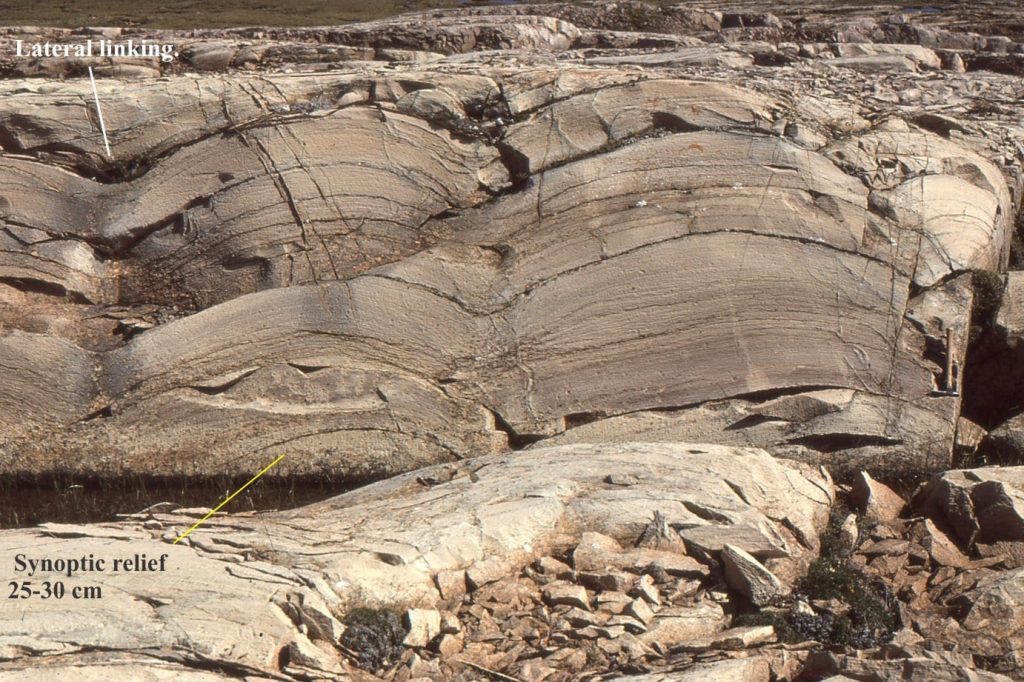

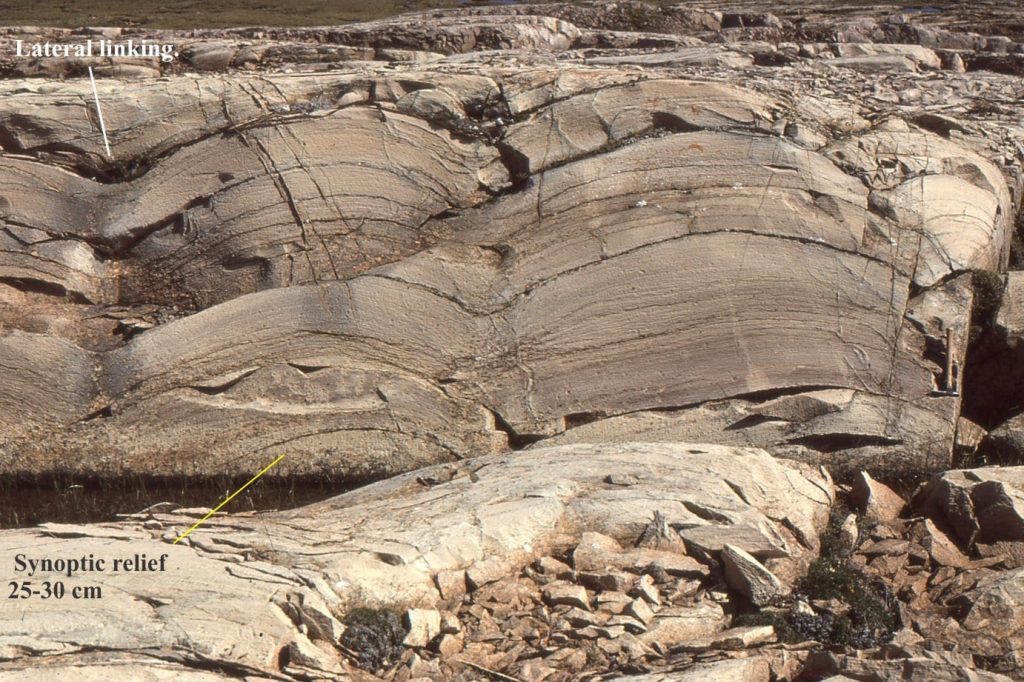

Moving across the platform, corresponding to higher stratigraphic levels, mounds coalesce into fewer but larger buildups, with concomitant increases in synoptic relief. Synoptic relief is a maximum 2m to 3m at the platform margin. Here, buildups consist almost entirely of wavy, undulating and crinkly laminates; digitate branching is far less common. In addition, smaller scale elongate mounds are superposed on the larger structures. Thin beds of mud and laminate rip-ups, floored by shallow scours, indicate the passage of storms. Disruption by storms is seen in all the buildups including those near the platform margin. This implies that the depth of the margin itself was close to storm wave-base.

The exposure in places allows one to walk out individual beds from mound crest through the adjacent trough to the opposite mound; the only thing that’s missing is the water over your head.

High synoptic relief reef mounds viewed towards the platform margin, slightly oblique to elongation axes. In places, individual beds can be traced across mounds. These large structures were constructed entirely of laminated cryptalgal laminates. Eastern Tukarak Island.

Small mounds commonly adorned the crests and flanks of the high relief structures. Their elongation directions parallel the trend of the larger mounds. Jacob’s Staff (centre) is 1.5m long. Eastern Tukarak Island.

Smaller-scale domes superposed on the large reef structures, are simple, laterally linked laminates, having synoptic relief in the range 20-30 cm. (hammer centre right). Eastern Tukarak Island.

Wavy cryptalgal laminates from an outer platform buildup, disrupted by a shallow scour surface and overlain by rip-up clasts. Disruption by storms was common. Also some nice stylolites.

Wavy and crinkly laminates make up the bulk of the high-relief buildups that grew on the middle and outer platform.

The slope

The transition from reef buildups to slope shale and carbonate rhythmites is abrupt, although a few small, isolated stromatolite domes occur immediately outboard of the platform margin, within slope mudrocks; these occurrences are inferred to represent the photic zone depth limit of stromatolite growth . The rhythmites are particularly striking, with alternating intervals of red and white dolomitized carbonate mudstones and calcilutites. There are a few graded beds containing more sandy sediment (mudstone fragments, ooids) and climbing ripples, deposited by turbidity currents. Clearly, some coarse-grained, shallow water sediment was moved onto the platform, perhaps through troughs between the mounds, eventually bypassing the margin. Slump structures also occur but like the turbidites, are not common.

Slope rhythmites composed of calcilutite and dololutite. The ‘lumpy’ appearance is mainly due to incomplete replacement of calcitic mud to dolomite; this is one of the few units in the Belcher stratigraphy that still contains some calcite. Left: A relatively continuous succession of rhythmites, cut by numerous small extension faults. Top right: Bouma c (climbing ripples) and thin d (laminated mud) intervals of a turbidity current. Sandy material in the c interval was derived from the inshore deposits. Bottom right: Dololutite with some terrigenous mud (red hues), interbedded with white calcilutite rhythmites.

The Mavor platform was dominated by muddy carbonate sediment. It was a large carbonate factory where the production line consisted entirely of cyanobacteria. Reef and slope stratigraphy indicate long-term transgression, conditions conducive to the viability of factory production. There are no chronostratigraphic controls on this part of the succession, but I speculate the cycle duration is roughly equivalent to a 3rd-order Sequence.

Links to other posts in this series:

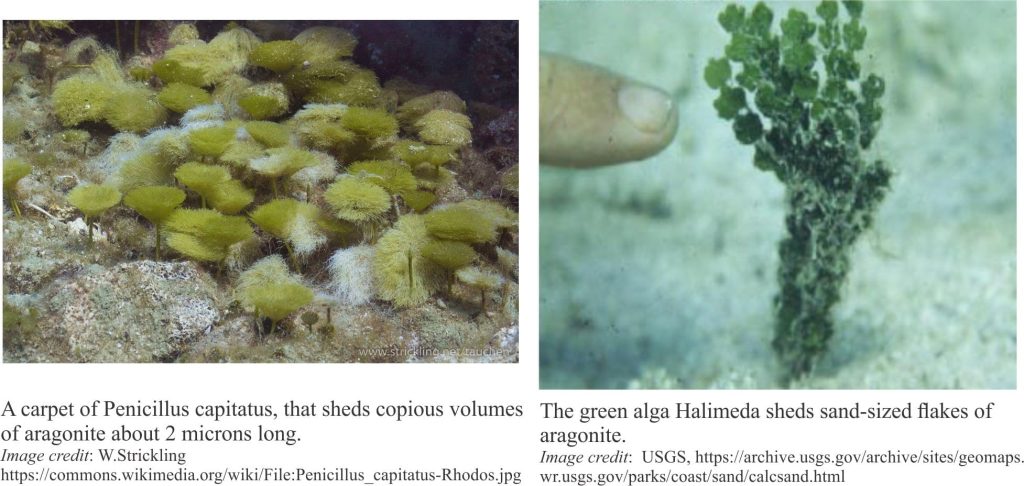

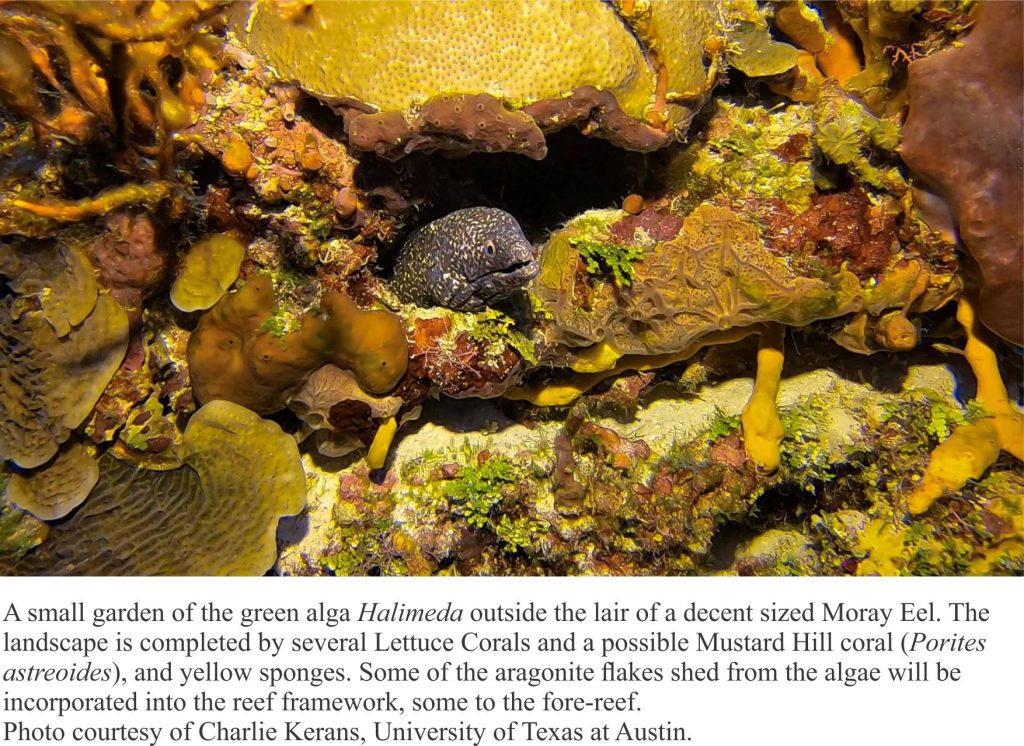

Mineralogy of carbonates; skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; non-skeletal grains

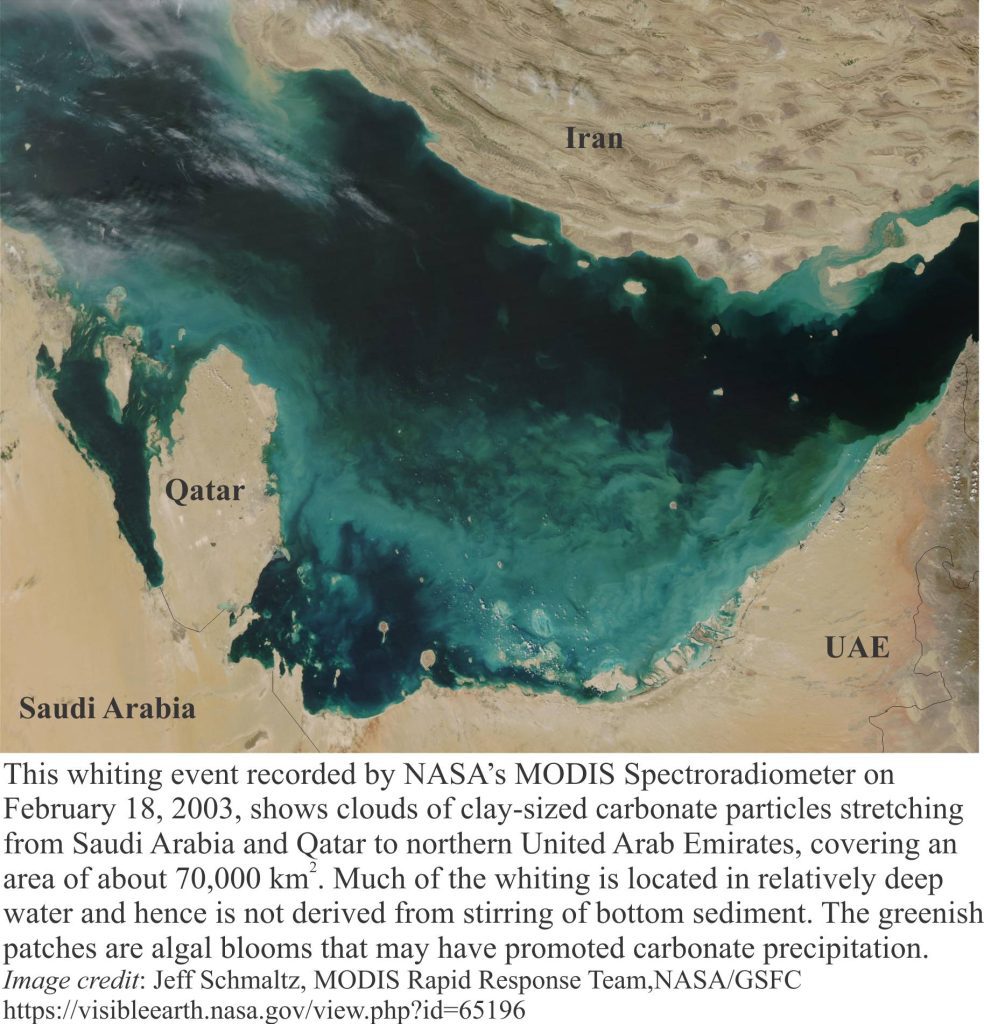

Mineralogy of carbonates; lime mud

Mineralogy of carbonates; classification

Mineralogy of carbonates; carbonate factories

Mineralogy of carbonates; basic geochemistry

Mineralogy of carbonates; cements

Mineralogy of carbonates; sea floor diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; Beachrock

Mineralogy of carbonates; deep sea diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; meteoric hydrogeology

Mineralogy of carbonates; Karst

Mineralogy of carbonates; Burial diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; Neomorphism

Mineralogy of carbonates; Pressure solution

References

Bosak, A.H. Knoll, and A.P. Petroff, 2013. The Meaning of Stromatolites. Annual Reviews of Earth & Planetary Science, v. 41, p. 21-44. Free Access. Lots of great references.

T.E. Playton, X. Janson and C. Kerans. 2010. Carbonate slopes and margins. In N.P.James and R Dalrmple (Editors), Geological Association of Canada, Facies Models 4, Chapter 18. P. 449-476. Available for download

E.P. Suosaari, R.P. Reid, and M.S. Andres, 2019. Stromatolites, so what?! A tribute to Robert N Ginsberg. Depositional Record, v. 5, p. 486-497. Open Access. Evaluates some of the main controversies with stromatolites and microbialites. Lots of great references.

B.D. Ricketts and J.A. Donaldson, 1989. Stromatolite reef development on a mud-dominated platform in the Middle Precambrian Belcher Group of Hudson Bay. In, H. Geldsetzer, N.P. James and G. Tebbutt (Eds.), Reefs, Canada and adjacent areas. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir 13.

H.D. Williams and others, 2011. Investigating carbonate platform types: Multiple controls and a continuum of geometries. Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 81, p.18-37. Good account of factors influencing platform and ramp geometries using 2D modelling. Available for download