This post is part of the How To… series

Crossbeds are ubiquitous in sedimentary rocks. They can be found on the deep ocean floor, the driest desert, and pretty well any depositional environment in between. They are most common in sandy deposits. They are less common, but no less important in gravels (e.g. low sinuosity – braided rivers). Crossbeds form where air and water flow across a bed of loose sediment, so long as the individual sediment grains are cohesionless (non-sticky). Mud crossbeds are rare because individual clay particles tend to bind to one another (a result of residual electric charges).

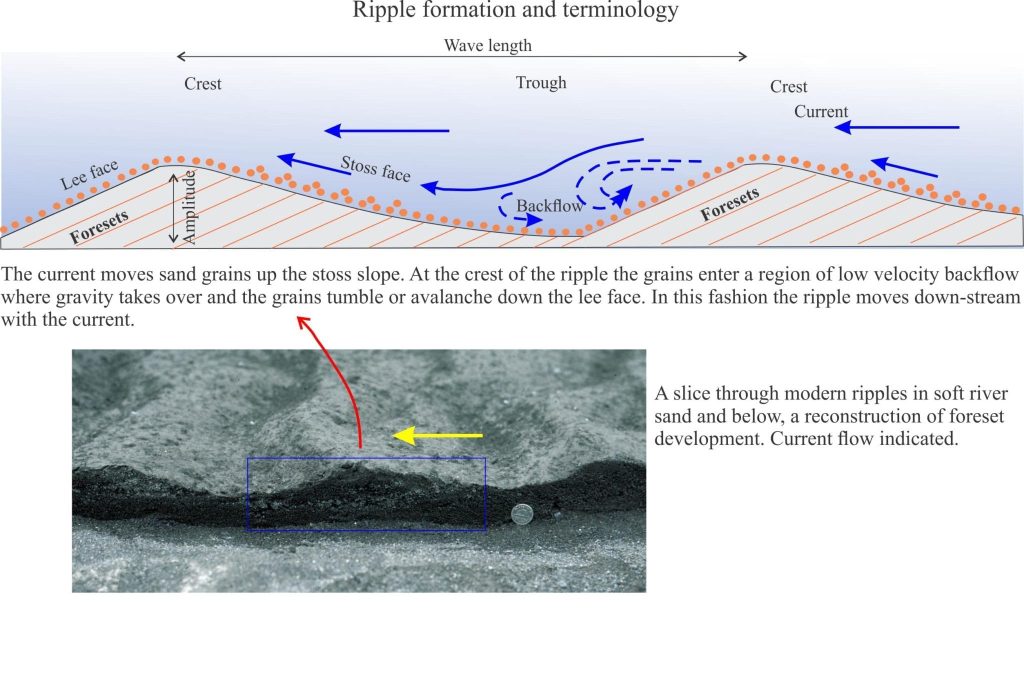

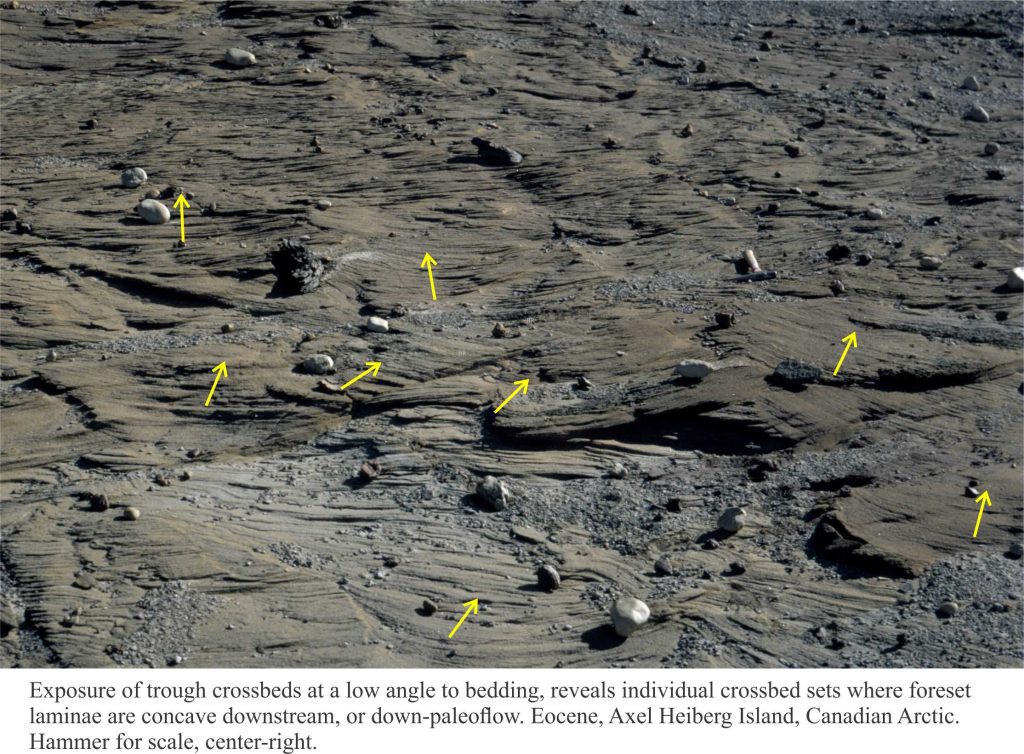

Crossbeds in the rock record are visible in bed cross-sections, or as exhumed 3D ripples and dunes on exposed bedding planes. The term crossbed refers to their internal structure; i.e. laminations that are usually inclined in the down-flow, or down-stream direction.

The laminae are called foresets. In a 2D cross-section view, a single crossbed consists of any number of foresets bound above and below by flat or curved boundaries. The geometrical arrangement of foresets, their bounding surfaces and their size or amplitude gives us the information needed to decipher:

- the kind of crossbed,

- the hydraulic conditions under which the crossbed formed, and to some extent

- the paleoenvironment in which they formed; keep in mind that most crossbeds can be found in a range of paleoenvironments but used in conjunction with other criteria such as body and trace fossils, sediment composition and stratigraphic trends (e.g. fining upward) will help pin-point specific depositional settings.

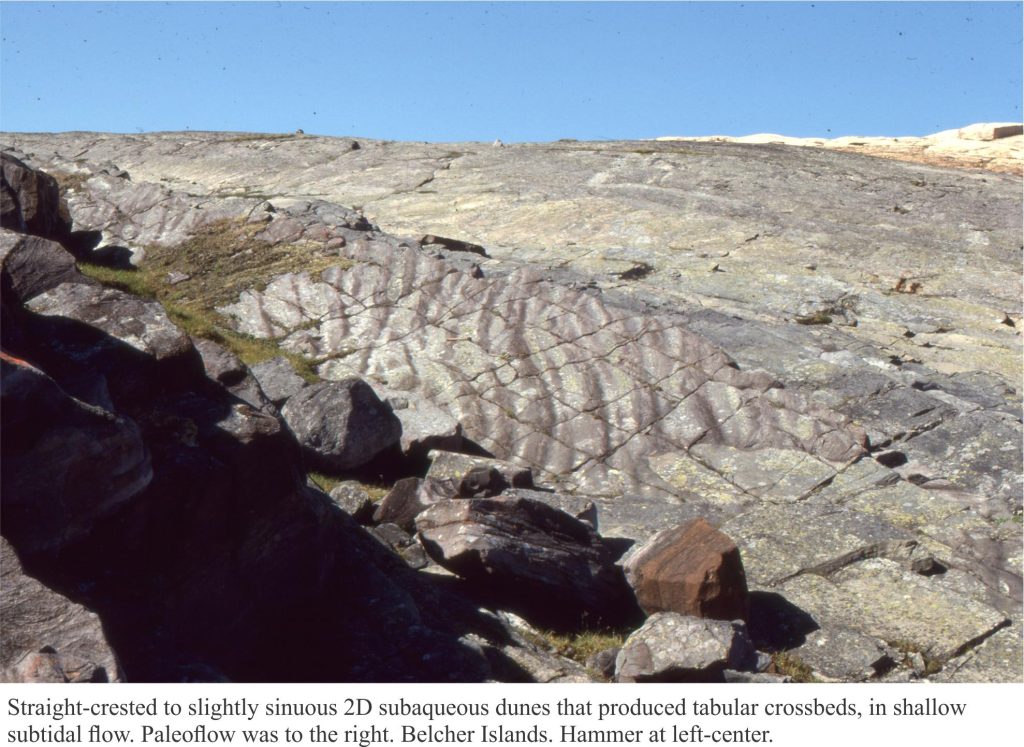

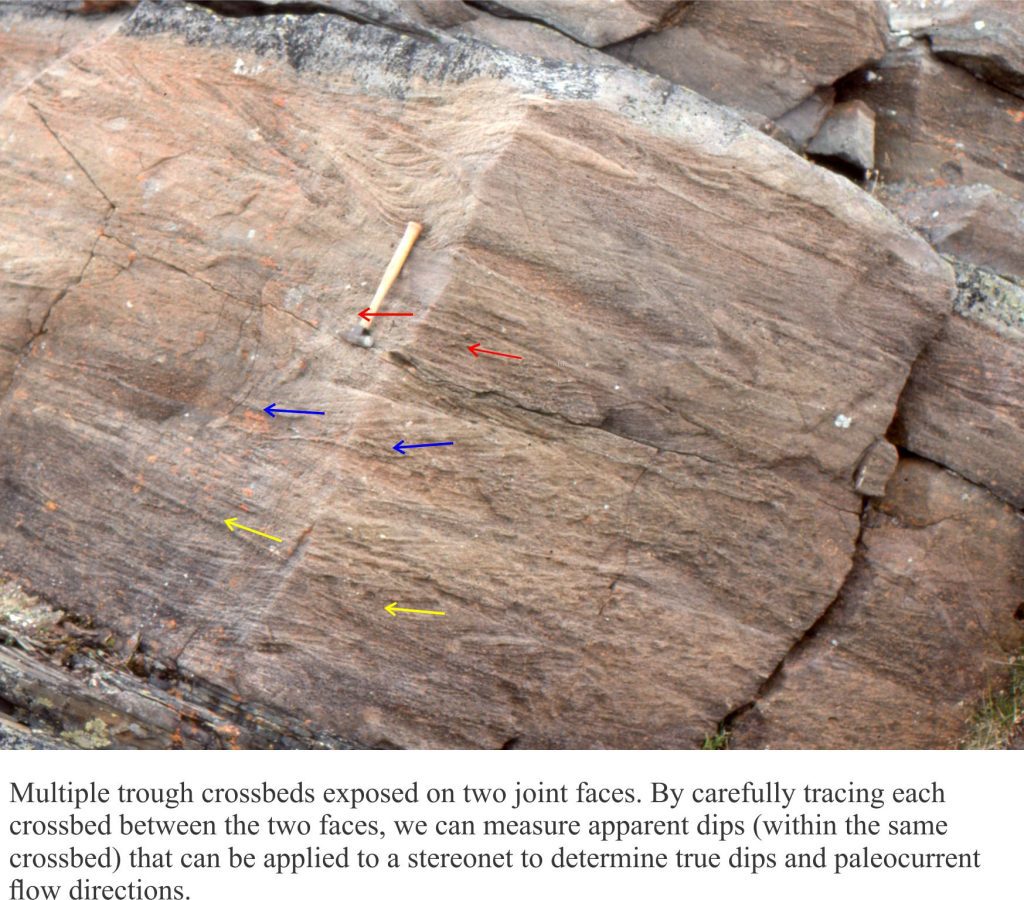

Our interpretations can be advanced further if we are lucky enough to see exhumed structures on bedding, such that we can define:

- the shape of the ripple or dune crest line (is it straight or sinuous?)

- the wavelength between successive ripple or dunes, and

a relatively unambiguous measure of ripple-dune migration across the bed (i.e. paleocurrents).

Most of our knowledge about ripples and dunes (collectively referred to as bedforms) and how they form has been garnered from studies of modern environments. Afterall, if on your walks across a tidal flat or subaerial dune field you see ripples that look identical to those preserved in rocks, it is quite reasonable to predict that the ancient bedforms developed in ways similar to the modern analogues (this is the Uniformitarian Principle at work).

In fact, they have also been videoed forming in real time on Mars.

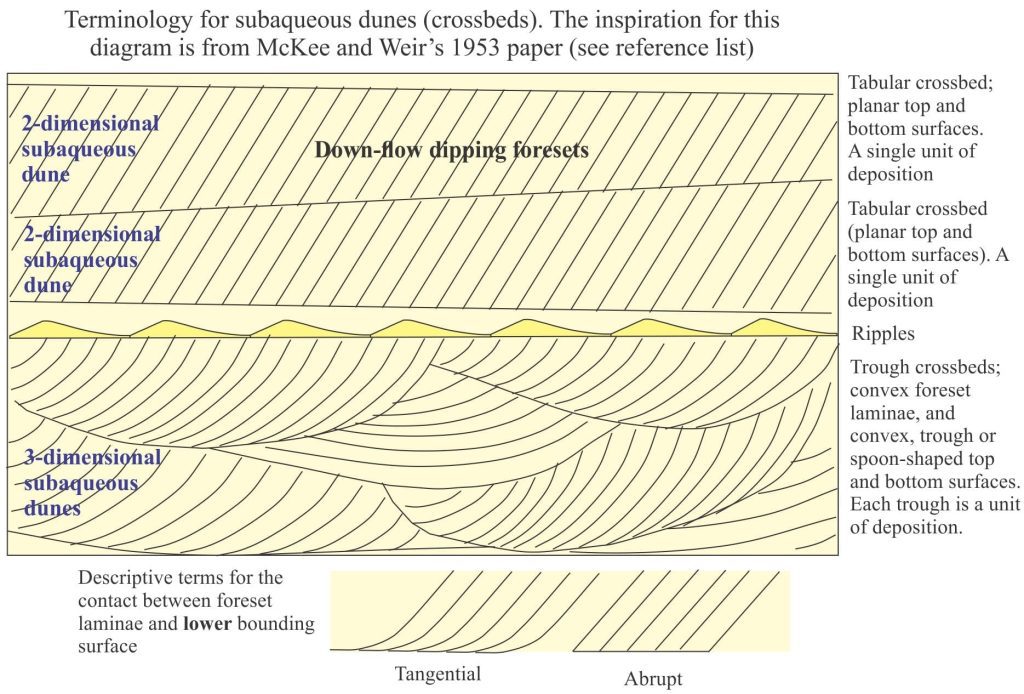

This terminology has evolved from an original 1953 description by McKee and Weir (see references at the end of the post). An SEPM workshop in 1987 (Ashley,1990) sought to incorporate in a revised terminology, the 3-dimensional aspects of bedforms larger than common ripples and their inherent hydraulic properties. They recommended that the term dune be used, with the basic distinction between subaerial and subaqueous dunes, of all sizes. Subaqueous dunes can be further separated into:

- 2 dimensional subaqueous dunes having relatively straight crest lines and planar foreset contacts; they correspond to tabular crossbeds (in the above diagram), and

- 3 dimensional subaqueous dunes having sinuous crest lines and spoon- or scour-shaped foreset contacts. These correspond to the classic trough crossbeds.

Trough crossbeds are most common in channelized, or confined flow (rivers, tidal inlets and channels, rip currents). Three dimensional subaqueous dunes tend to form at higher current velocities than their 2D counterparts.

The SEPM nomenclature is widely used, but deeply entrenched terms like trough and tabular crossbed are still popular.

Here are some classic older texts on the topic (and just because they are older than 10 years doesn’t mean they are irrelevant!)

Allen, JRL. 1963. The classification of cross-stratified units. With notes on their origin. Sedimentology, v. 2, p.93-114

Ashley, G.M. 1990. Classification of large-scale subaqueous bedforms: A new look at an old problem. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v.60, p. 160-172.

McKee, E.D. and Weir, G.W. 1953. Terminology for stratification and cross-stratification. Geological Society of America Bulletin v. 64, p. 381-390.

Some more useful posts in this series:

Sedimentary structures: Fine-grained fluvial

Determining stratigraphic tops

Identifying paleocurrent indicators

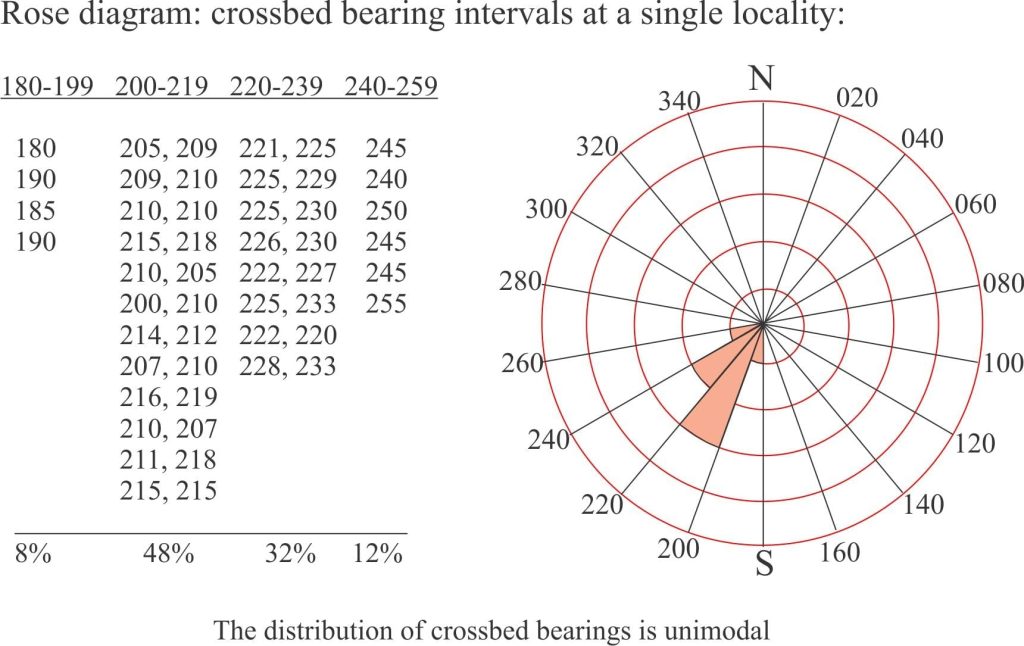

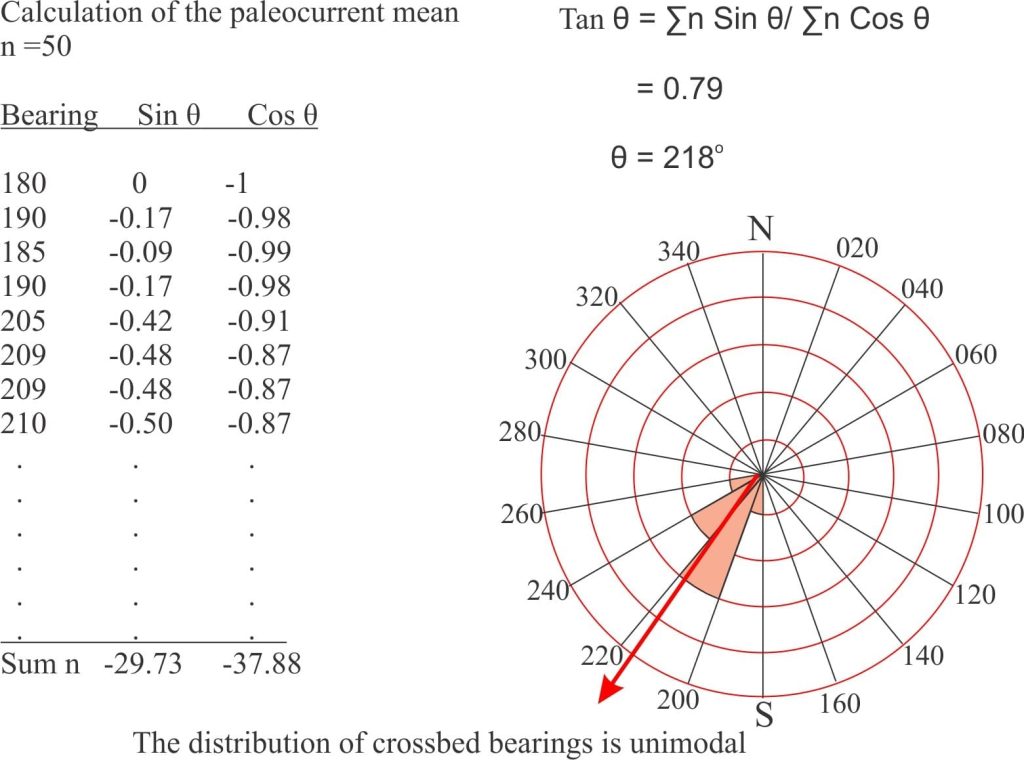

Measuring and representing paleocurrents

The hydraulics of sedimentation: Flow Regime

Sediment transport: Bedload and suspension load