Parasequences are the building blocks of shallow marine systems tracts.

The stratigraphy of ancient, shallow marine deposits is commonly presented in outcrop, core, and wire-line logs as cyclic repetitions of shallowing-upward facies, an observation that dates back almost two centuries. Each cycle contains facies transitions from some part of the shelf or platform, to shallower conditions (for example shoreface through shoreline). The ubiquity of these 4th – and 5th -order cycles in the rock record, and the recognition that collectively they comprise larger 3rd -order cycles, led early proponents of sequence stratigraphy to introduce the concept of parasequence. For Van Wagoner et al. (1988), parasequences are the building blocks of stratigraphic sequences. They define parasequences as (op cit, p. 39):

“A relatively conformable succession of genetically related beds or bedsets bounded by marine flooding surfaces and their correlative surfaces.”

This definition has survived, reasonably intact, the vagaries of geological debate – witness the attempts to find a common sense of purpose in sequence stratigraphic terminology by Catuneanu et al. (2010, 2011); a group of co-authors all at the forefront of sequence stratigraphic analysis.

The definition contains several implied and explicitly stated conditions:

- Parasequences are fully marine.

- In the original definition, parasequences are bound by marine flooding surfaces and their correlative surfaces; later definitions have removed reference to the correlative Flooding surfaces represent abrupt changes in water depth during transgression; the change in facies across the flooding surface is also abrupt, from shallow to deep. This means that fluvial successions, and at the other end of the water depth scale, basin-floor fans, are excluded. This does not mean that 4th and 5th order cycles do not occur in fluvial and submarine fans, but that their equivalence in time and space is difficult to demonstrate.

- A relatively conformable succession – Brief diastemic breaks are common, for example storm scour surfaces across the shoreface, but there are no unconformities or disconformities.

- Genetically related beds – This phrase refers to two conditions: that successive facies are associated in time and space. For example, subtidal-intertidal-supratidal deposits are linked by the dynamics of sedimentation (tidal flux, currents, waves), biotas, and for carbonates and evaporites, seawater chemistry. This relationship, together with the requirement for a comfortable succession, also means that Walther’s Law applies – ‘‘. . . only those facies and facies-areas can be superimposed primarily which can be observed beside each other at the present time’’ (Walther 1894).

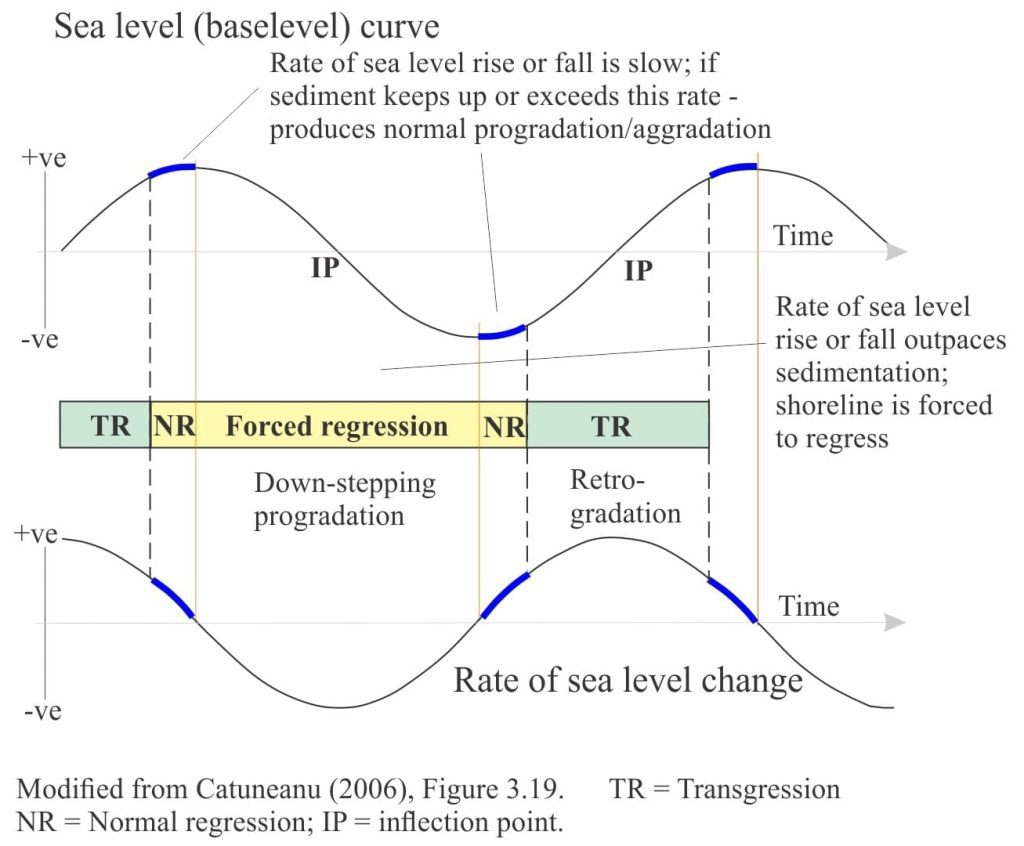

Parasequences represent relatively short-lived periods of progradation that are superimposed on, or punctuate 3rd order regressive or transgressive trends. As such, the most common stratigraphic facies trends shallow upward. Depending on the relative rates of sediment supply and sea level change, the stacking of parasequences will result in 3rd order:

- Progradation (possibly with a component of aggradation), where the normal regressive (seaward) shoreline trajectory of successive parasequences is approximately horizontal,

- Progradation during forced regression where successive shorelines have a down-stepping trajectory, and

- Progradation during transgression where the step-like shoreline trajectory of successive parasequences is retrograde, or landward.

Three examples of parasequences

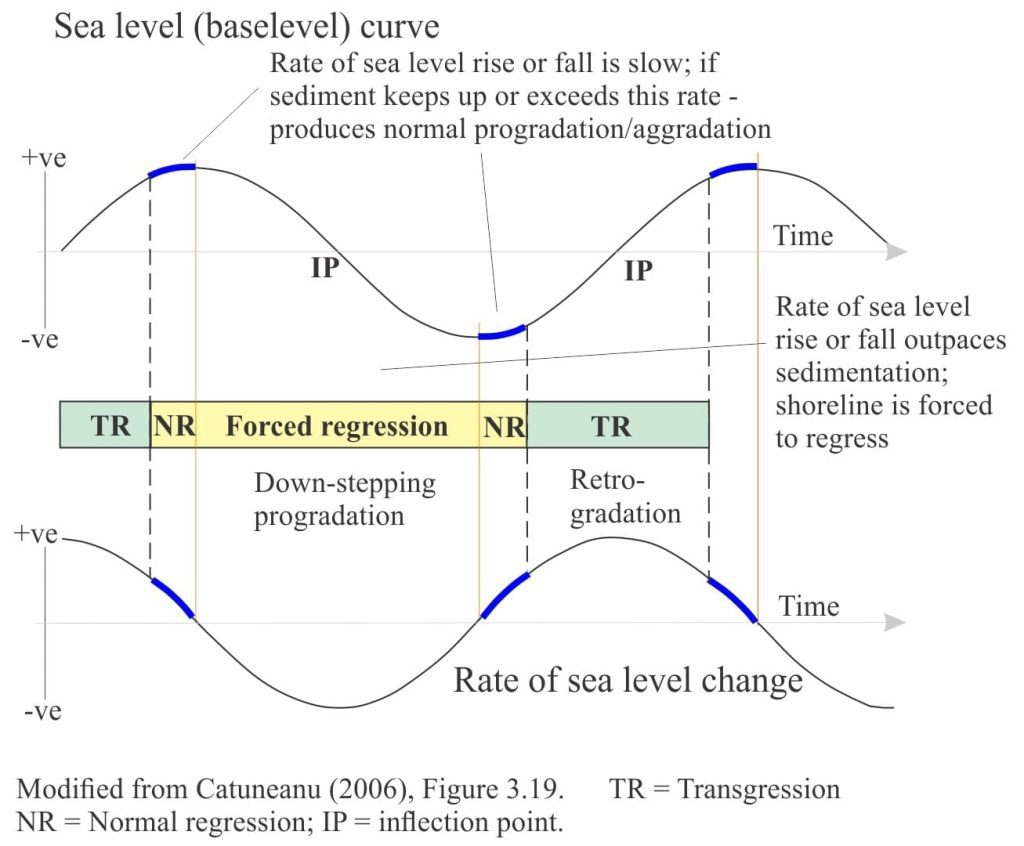

For each example, refer to the schematic depositional trends depicted in the sea level curve below.

Stages of regression and transgression in relation to relative sea level, in a sequence stratigraphy context

Bowser Basin, British Columbia

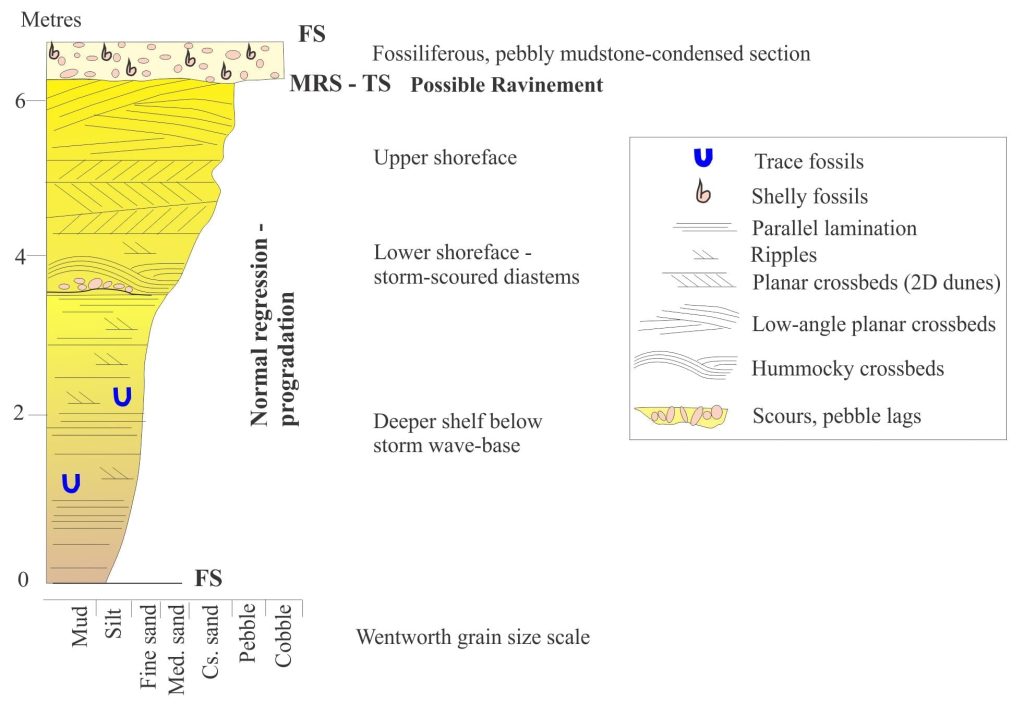

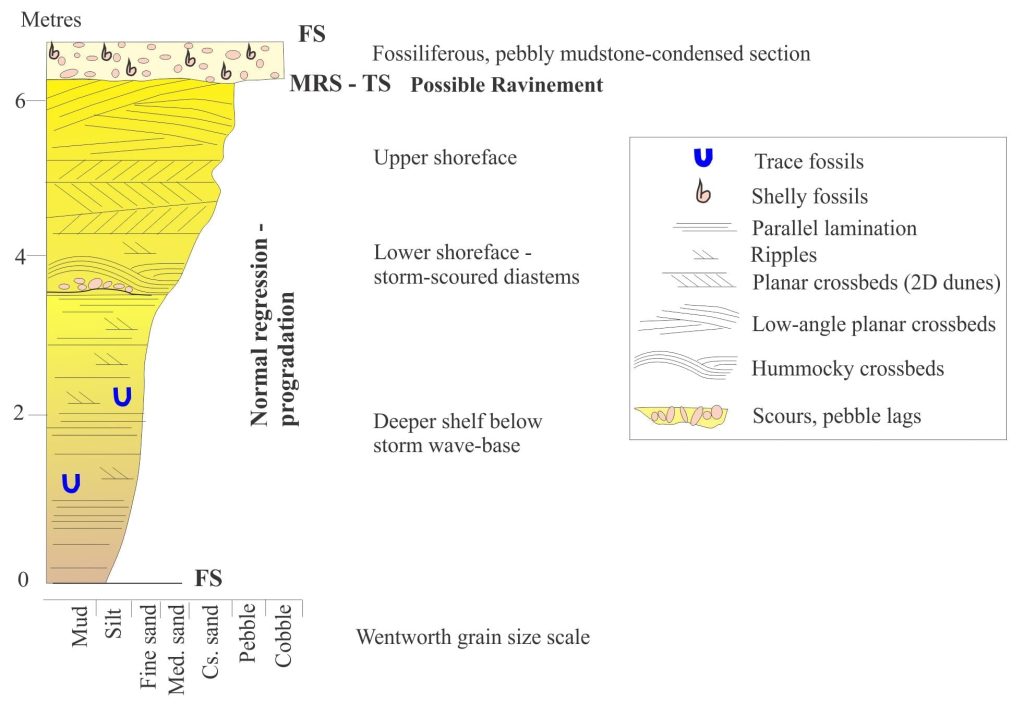

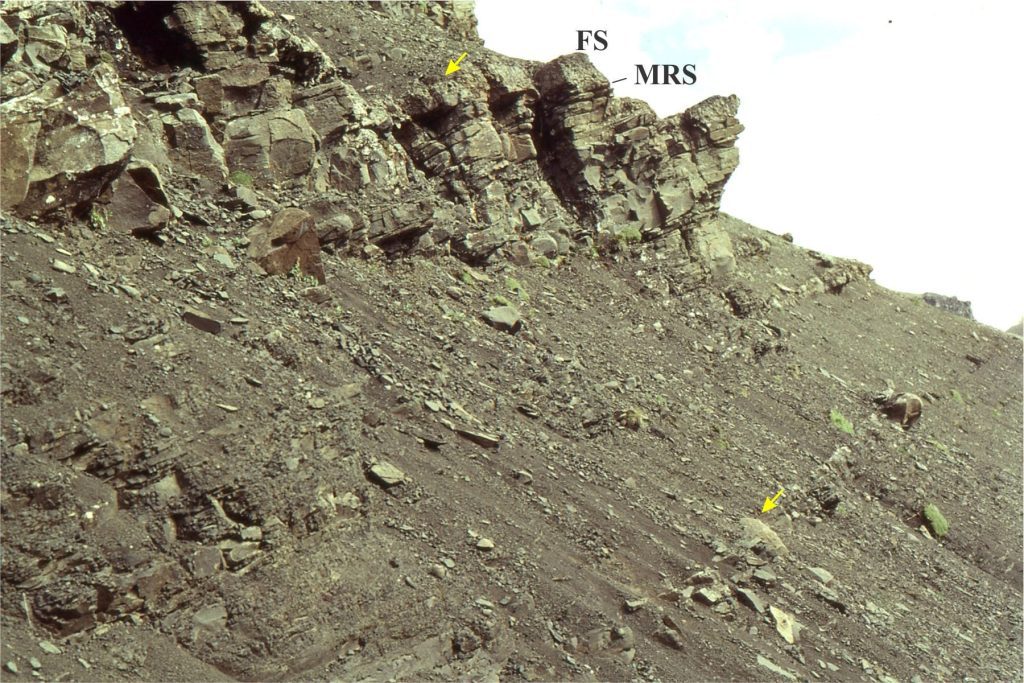

Middle Jurassic shelf deposits in Bowser Basin have well developed cyclicity represented by coarsening upward mudstone through sandstone successions, 5m to 20m thick. A typical example is shown below (refer to the diagram):

An example of a coarsening-shallowing upward parasequence from the Middle Jurassic of Bowser Basin, (Mt. Tsatia). The outcrop version is shown below.

- Grey mudstone interbedded with thin siltstone and sandstone at the base, gives way to gradually thicker and more frequent sandstone beds. These facies represent parts of the shelf that are deeper than storm wave-base.

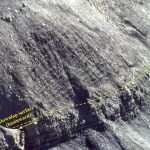

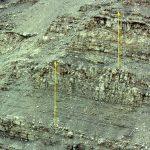

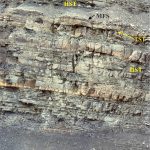

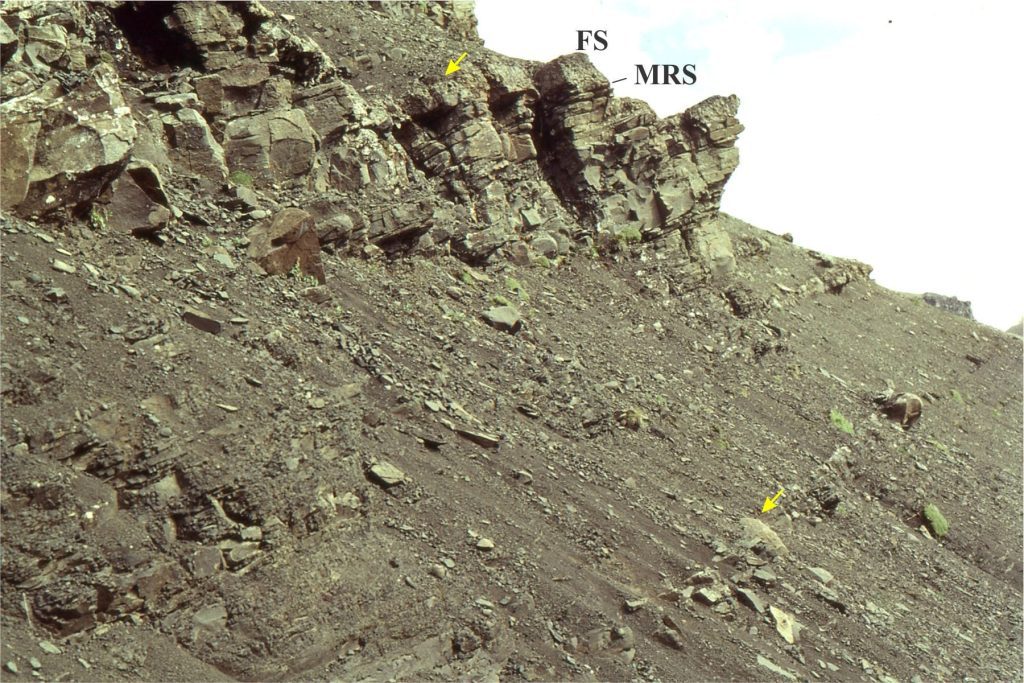

Coarsening-upward shelf parasequence, Bowser Basin. The cycle top and base are indicated by arrows; it is about 7m thick. Hummocky crossbedding and the transgressive, condensed, calcareous mudstone are shown in separate images. MRS = maximum regressive surface (or transgressive surface); FS = marine flooding surface.

- Hummocky crossbeds are common in the lower part of the resistant sandstone beds; these structures denote a relative position on the shelf corresponding to storm wave- base.

Hummocky crossbedding developed at storm wave base. The hammer lies just below a basal pebble layer that was deposited by a bottom-hugging density current during collapse of a storm surge. Tsatia Mt. Bowser Basin.

- Sandstones in the upper 2-3m contain planar crossbeds, and a few pebble-lined scours that probably indicate the passage of storm waves across the upper shoreface.

- The sandstones are capped by a fossiliferous, pebbly, calcareous mudstone. The base of the mudstone is slightly erosional and is interpreted as a maximum regressive surface (MRS) or transgressive surface (TS), although the erosional contact may indicate ravinement during initial transgression. The top of the pebbly mudstone is a marine flooding surface (FS) and represents maximum transgression (or close it).

The transgressive part of a typical shelf parasequence; Bivalves and bryozoa abound. The unit is highly calcareous. The underlying sandstones are crossbedded. MRS = maximum regressive surface (or transgressive surface); FS = marine flooding surface. Lens cap bottom centre.

Overall, the parasequence represents progradation at high sedimentation rates during normal regression, followed by transgression.

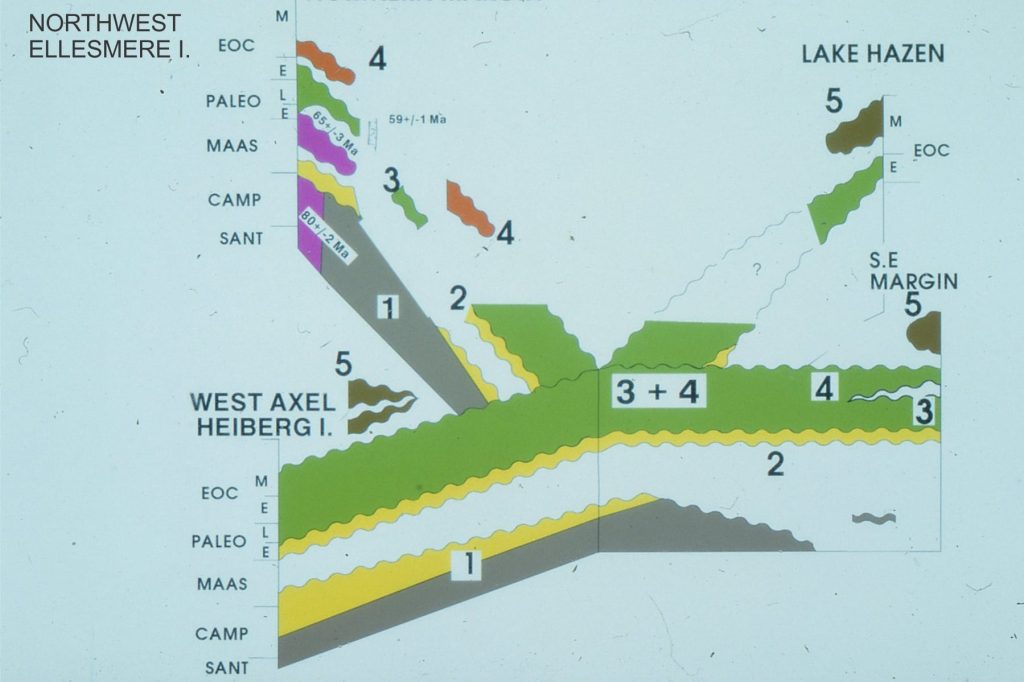

Sverdrup Basin, Canadian Arctic

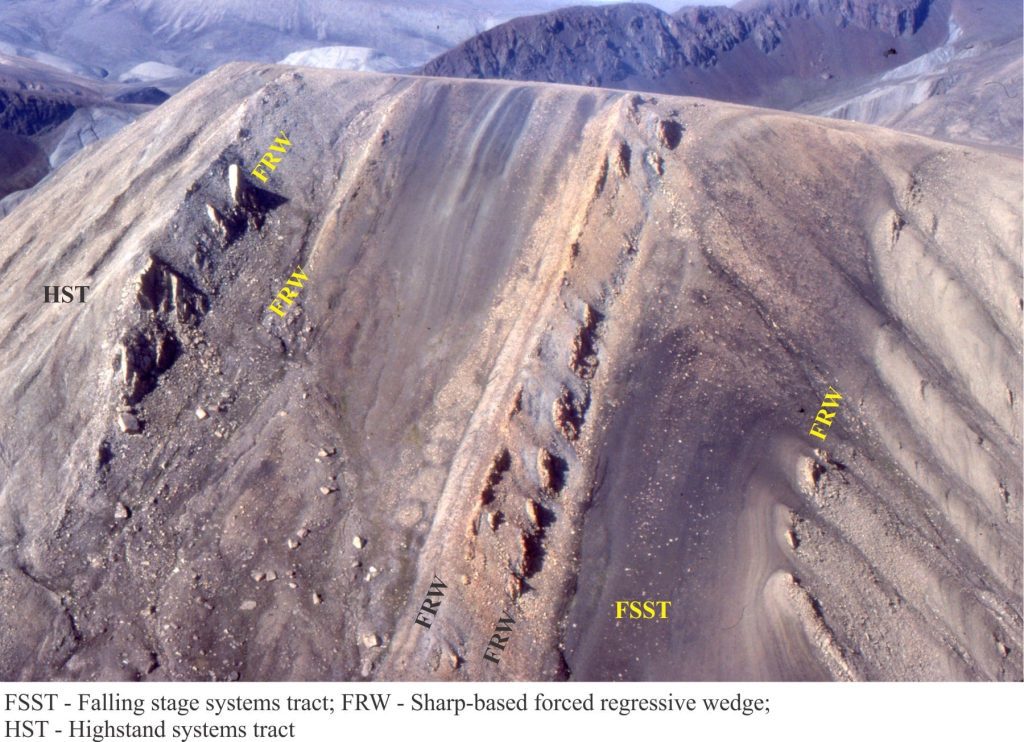

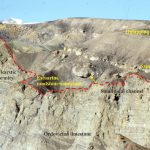

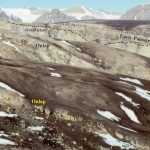

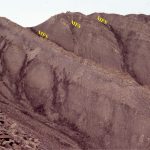

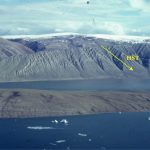

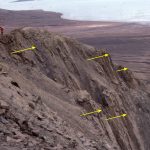

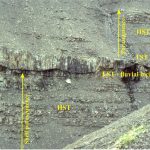

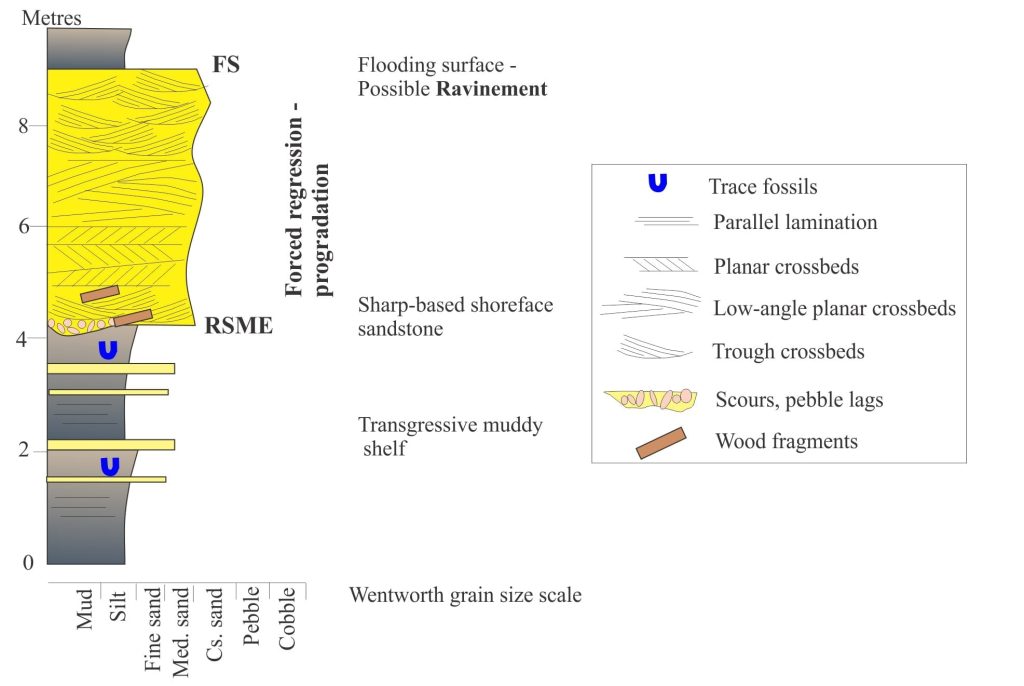

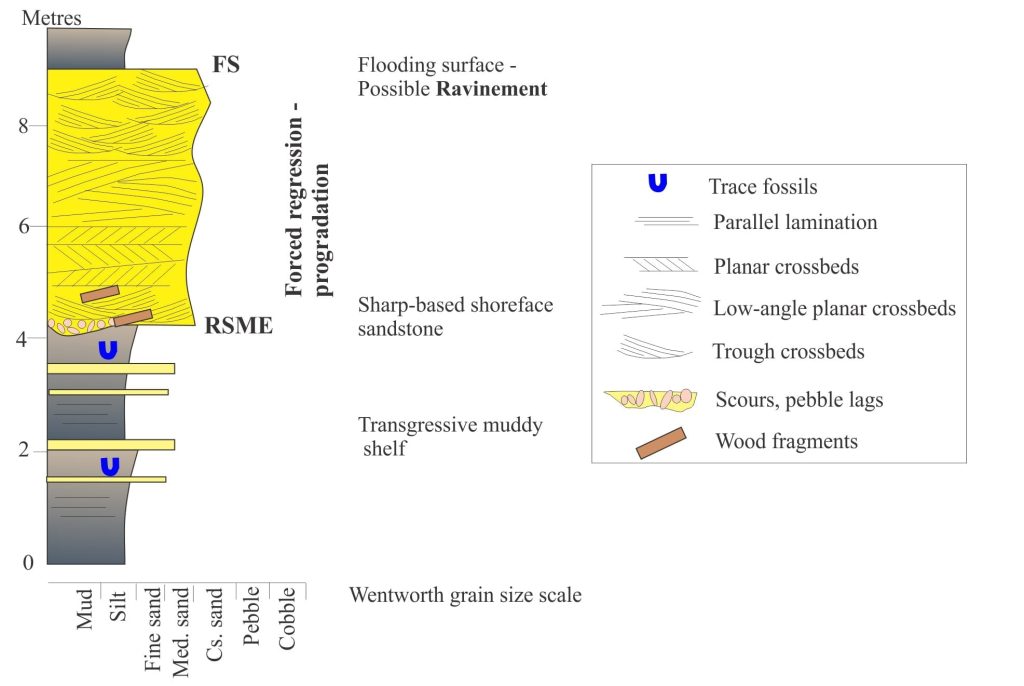

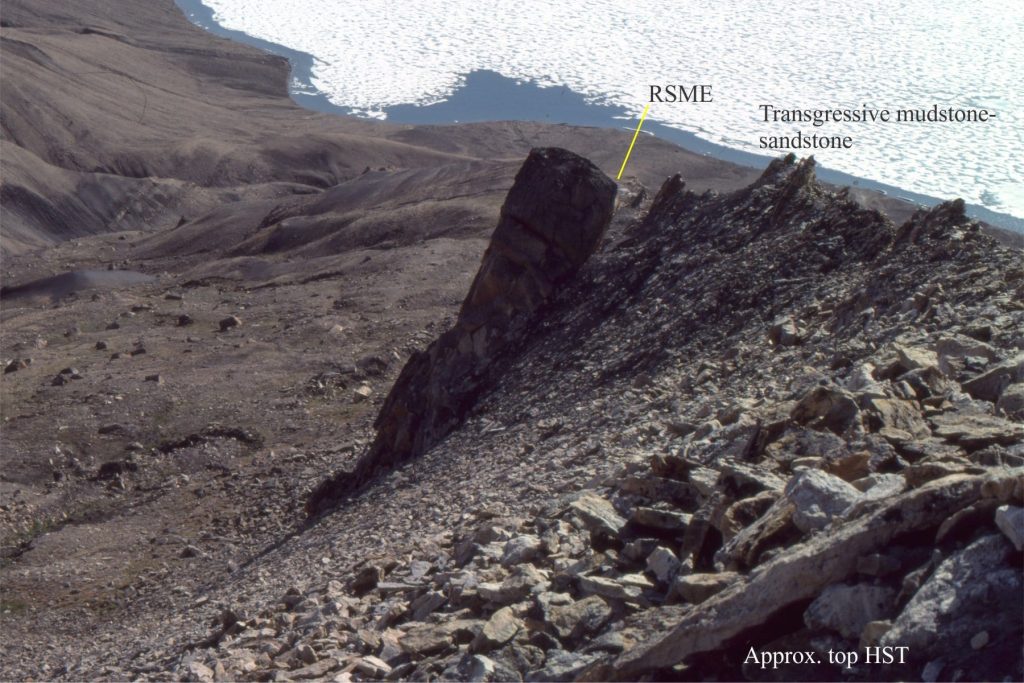

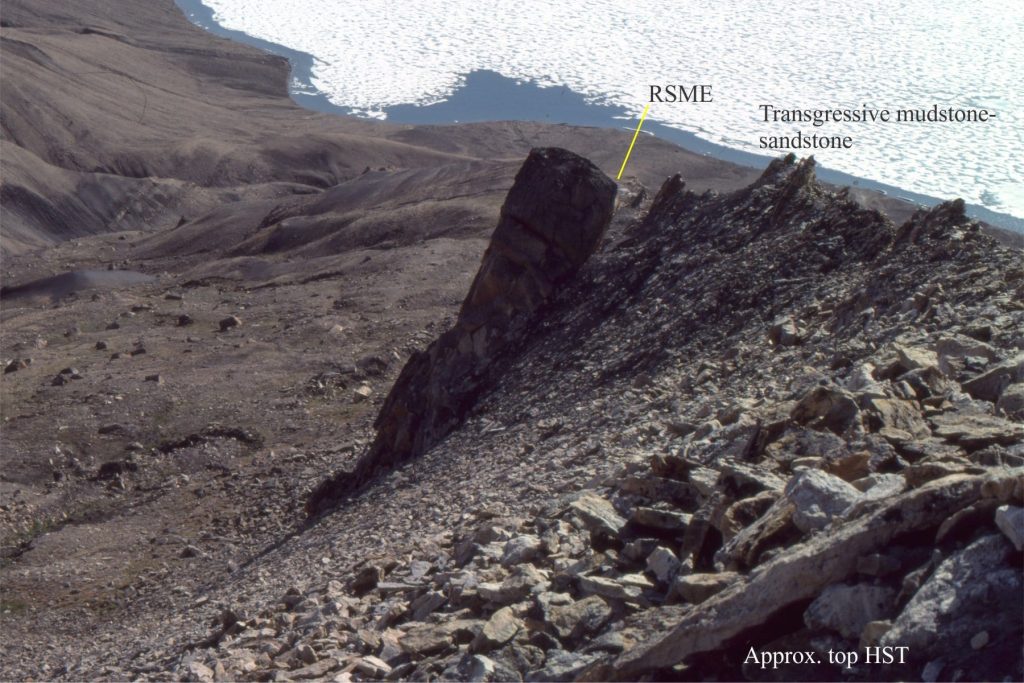

Parasequences in the Strand Bay Formation (Middle to Late Paleocene) represent forced regression following a period of (Early Paleocene) highstand progradation-aggradation. The example shows:

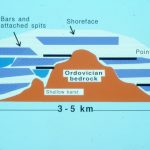

Schematic representation of a sharp-based, forced regressive sandstone wedge, Middle-Late Paleocene, Axel Heiberg Island. RSME = Regressive Surface of Marine Erosion; FS = Marine flooding surface.

- A resistant sandstone unit that has an abrupt, erosional base (usually with pebble lags and coalified wood fragments), and an equally abrupt top. The bulk of the sandstone contains abundant planar and trough crossbeds that represent deposition across a high-energy shoreface.

- The sandstone is sandwiched between mudstones and siltstones that represent transgressive, outer-shelf deposits.

- The abrupt contact at the top of the sandstone is a flooding surface, but its preservation was complicated by shoreface ravinement during the early stage of transgression.

A sharp-based sandstone wedge deposited during forced-regression. This exposure at Expedition Fiord, Axel Heiberg Island. RSME = Regressive surface of marine erosion; FS = marine flooding surface, HST = top of underlying Highstand succession.

Belcher Islands, Hudson Bay

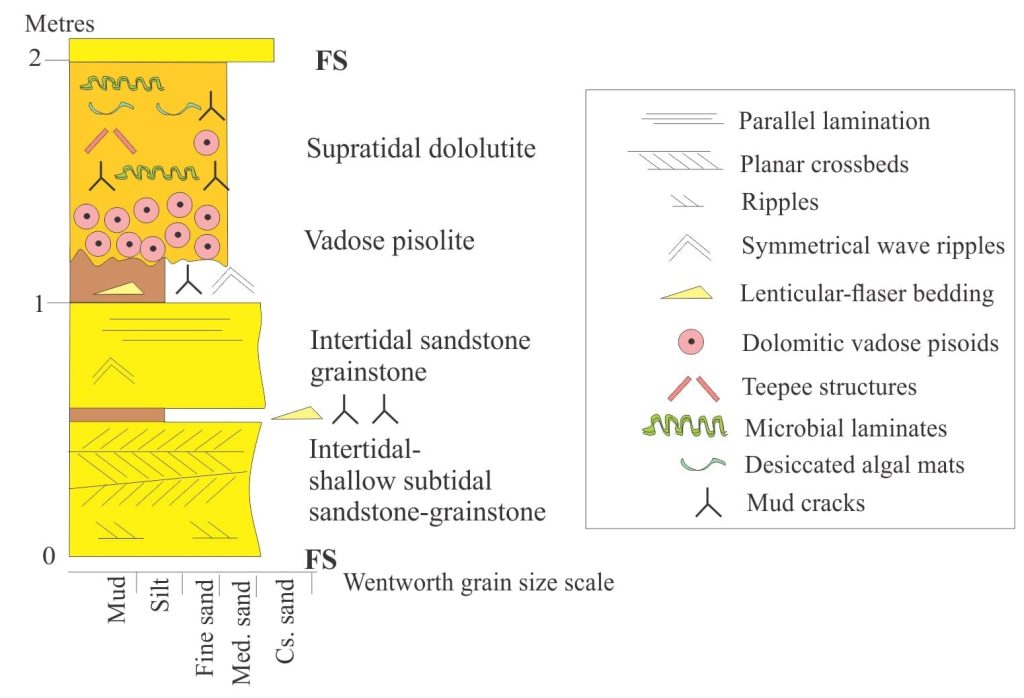

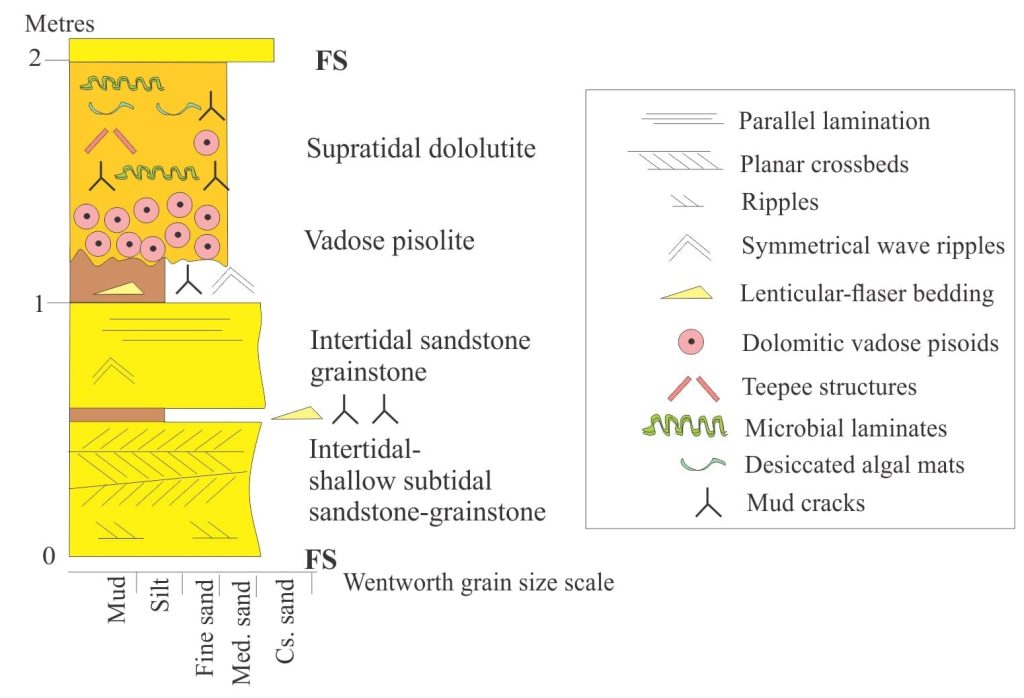

The Paleoproterozoic Fairweather Formation (Belcher Islands) contains mixed siliciclastic-carbonate facies organized into shallowing upward cycles, 2-5m thick. In a typical cycle we see:

Schematic representation of mixed siliciclastic-carbonate tidal cycles in the Paleoproterozoic Fairweather Formation, Belcher Islands, Hudson Bay.

- Basal siliciclastic sandstone and dolomitic grainstone, interbedded with dolomitic mudstone; planar and herringbone crossbeds, lenticular ripple bedding, and reactivation surfaces indicate shallow subtidal to intertidal conditions.

- Sandstones higher in the succession have the same composition, but the sedimentary structures indicate progressively shallower conditions as desiccation cracks become more frequent.

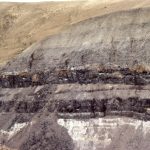

Mixed, crossbedded siliciclastic-grainstone facies of intertidal persuasion, overlain by pisolitic dolostone. The contact appears abrupt but in fact is diffuse over several centimeters, and represents a ‘weathering-diagenetic front’. Hammer at center.

- The overlying carbonates (all dolomitized) consist of highly distinctive, vadose pisolitic dolostone (e.g. caliche). The evidence for this is:

- Close-fitted packing of pisoids,

- Some elongation of individual pisoids ( gravity induced),

- Discordances between pisoids caused by multiple episodes of dissolution and precipitation, and,

- The irregular, diffuse contact with underlying sandstones that developed during soil-caliche weathering and fluctuating watertables.

Successive vadose pisolite beds formed by multiple periods of in-situ precipitation and dissolution attendant on fluctuating watertables and the occasional marine flooding of supratidal flats by storm and spring tides.

This post is part of the How To…series on Stratigraphy and Sequence Stratigraphy

Other posts in this series on Stratigraphy and Sequence Stratigraphy

Stratigraphic surfaces in outcrop – baselevel fall

Stratigraphic surfaces in outcrop – baselevel rise

A timeline of stratigraphic principles; 15th to 18th C

A timeline of stratigraphic principles; 19th C to 1950

A timeline of stratigraphic principles; 1950-1977

Baselevel, Base-level, and Base level

Sediment accommodation and supply

Autogenic or allogenic dynamics in stratigraphy?

Stratigraphic cycles: What are they?

Sequence stratigraphic surfaces

Shorelines and shoreline trajectories

Stratigraphic trends and stacking patterns

Stratigraphic condensation – condensed sections

Depositional systems and systems tracts

Which sequence stratigraphic model is that?